- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Profiling Property Crimes

About this book

This title was first published in 2000. Each of these commissioned papers explores the varieties of different crimes against property. The actions that differentiate types of arson, burglary, workplace crime and robbery are examined to provide insights of relevance to criminologists, psychologists and criminal investigators.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Profiling Property Crimes

DAVID CANTER AND LAURENCE ALISON

The psychological issues that form the foundations for answering a number of important questions in criminal investigations are considered in this volume. These are shown to have their roots in the psychological study of individual differences. In the criminal context these differences relate to important variations between types of crimes and also within any type of crime. The notion of a hierarchy of criminal differentiation is introduced to highlight the need to search for consistencies and variations at many levels of that hierarchy. Consideration of this hierarchy also lends support to a circular ordering of criminal actions as a parallel with the colour circle. In developing the constituents of this ‘radex’ structure, it is proposed that the chapters in this volume support distinctions between criminals in terms of the intensity and seriousness of their crimes, the nature of their transactions with their explicit or implicit victims, the amount and type of expertise they bring to their crimes and the organisational and social contexts within which their crimes occur. The studies in this volume, then, show a slowly evolving behavioural science of crime that approaches the study of criminal actions from an objective, often statistical viewpoint rather than one based on personal intuition and clinical experience

David Canter is Director of the Centre for Investigative Psychology at the University of Liverpool. He has published widely in Environmental and Investigative Psychology as well as many areas of Applied Social Psychology. His most recent books since his award winning ‘Criminal Shadows’ have been ‘Psychology in Action’ and with Laurence Alison ‘Criminal Detection and the Psychology of Crime’.

Laurence Alison is currently employed as a lecturer at the Centre for Investigative Psychology at the University of Liverpool. Dr Alison is developing models to explain the processes of manipulation, influence and deception that are features of criminal investigations. His research interests focus upon developing rhetorical perspectives in relation to the investigative process and he has presented many lectures both nationally and internationally to a range of academics and police officers on the problems associated with offender profiling. He is affiliated with The Psychologists at Law Group - a forensic service specialising in providing advice to the courts, legal professions, police service, charities and public bodies.

Offender Profiling Series: IV - Profiling Property Crimes

Edited by D. Canter and L. Alison. © 2000 Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot, pp 1-30

Fundamental Questions

Three psychological issues form the foundations for answering a number of important questions in criminal investigations:

- The selection of behaviours (information collection). What are the important behavioural features of the crime that may help identify and successfully prosecute the perpetrator?

- Inferring characteristics (deriving conclusions from data). What inferences can be made about the characteristics of the offender that may help identify him/her?

- Linking offences (identifying consistencies). Are there any other crimes that are likely to have been committed by the same offender?

All three are derivations of questions crucial to other areas of psychology. They involve concepts associated with the significant differences between one person and another and the features of one individual’s behaviour that remain constant over different situations. It is therefore not surprising then that many of the concepts developed by psychologists over the last century, particularly in the field of personality and individual differences have relevance for the study of crime. Importantly, these issues are relevant to the investigations of all crimes, not just those that catch the newspaper headlines, like serial murder.

There may not appear to be any important psychological issues to explore when a robbery is committed for financial gain or a building set on fire to claim the insurance or exact revenge. The actions will appear to be explained as merely criminal mentality in the pursuit of gain. But any such explanations only touch the surface of the investigative questions noted above; questions about the salient qualities of the crime and the relationship of those qualities to other crimes and other characteristics of the offender. These questions and the psychological issues from which they grow are as relevant to the investigation of property crime as they are to crimes against the person.

Profiling and its Roots in the Psychology of Individual Differences

The study of the differences between individuals has been a concern of psychologists since the earliest emergence of modem empirically based psychology. It can be traced back at the very least to Sir Francis Galton in the late nineteenth century who measured variations in the aspects of people’s size and weight as well as their intellectual functioning. Out of this work grew the development of intelligence tests and other assessments of people’s abilities and aptitudes. Further explorations of differences in the way people relate to others and see themselves emerged later, under the general heading of the assessment of personality. More focused studies of the variations between people in the opinions they held about particular entities, referred to as ‘attitudes’, also became an aspect of the study of the important ways in which one person differed from another.

What is particularly noteworthy about these studies of individual differences is that they examine the actions and verbal reports of people directly. They do not attempt to infer some hidden engine driving people, a ‘motive’, that is the explanation of their deeds. Instead these studies recognised that for a variety of reasons, that have their roots in individuals genetics, upbringing and life experiences there will be observable and measurable differences between one person and another. There are many forms of explanation that are offered as to why these differences occur. The explanations go beyond the reason that individuals themselves may offer for their actions. As such they recognise that the motivation that a person may put forward for their actions is only one of a number of possible explanations and not necessarily the explanation most useful for understanding that person’s actions.

In relation to criminals this psychological perspective gives much more emphasis to a careful consideration of what offenders do, their actions, and the salient characteristics that distinguish one criminal’s actions from another’s, rather than an attempt to build explanations on inferences about putative motives.

An especially clear illustration of this in the present volume is Lobato’s study of the relationships between measures of personality and the types of weapons used by offenders [5]1. She uses standard measures of personality used in many areas of psychology and shows how the correlations they have with type of weapon use help us to understand the processes that give rise to the use of weapon. In essence, not too surprisingly, extroverts are more likely to use powerful, rather dramatic firearms, where introverts have a tendency to use knives. In what sense is degree of introversion a ‘motive’? Yet knowledge of the personality characteristics an offender is likely to have can be combined with other inferences to help winnow down the most likely suspect from a number of possibilities.

Psychologists as the Original ‘Profilers’

Sadly, the mass media fascination with violent, sexually related crimes and criminals has encouraged the belief that the study of the differences between criminals, and the making of inferences about their characteristics, is some unique area of expertise quite divorced from the main currents of contemporary psychology. The myth that is promulgated, attempts to characterise this process as originating solely from the speculations of US special agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. These speculations have been termed ‘profiling’, or more fully ‘offender profiling’, ‘psychological profiling’ or ‘criminal personality profiling’. Yet a moment’s reflection makes it clear that the description of the general characteristics of a person on the basis of a limited amount of information about them, has scientific roots in the concepts of psychometric testing. These concepts existed long before the FBI was created.

As Delprino and Bahn’s (1988) survey of psychological services in US police departments shows, psychologists were giving opinions to their local police forces about the characteristics of criminals before the FBI ‘Behavioral Science Unit’ was established. This was a natural outgrowth of their major involvement in the development of predictive profiles of people applying for jobs in the police force. This procedure, otherwise known as ‘assessment of applicants’, as well as their advice on clinical matters relating to suspects, such as fitness to plead and other aspects of their mental health status, has been an enduring contribution for some time.

Artificially Imposed Limitations on the Nature of Profiling

Along with the myth that the process of inferring offender characteristics from criminal actions had its genesis in the FBI’s work is the suggestion that psychological insight into a criminal is most valuable when the offence does not appear to be ‘normal’. The usual characterisation of an abnormal offence is one in which there is no obvious motive, such as crimes that do not have a clear instrumental, probably financial, purpose. This tends to put the emphasis on rape, and the murder of strangers and other violent crimes. Indeed, in their introduction to The Crime Classification Manual Ressler et al., (1992) quote with obvious approval Bromberg’s (1962) finding that ‘Those behaviour patterns involved in criminal acts are not far removed from those of normal behaviour’. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that their ‘Manual’ is little more than the codified opinions of a wide range of police officers. It therefore offers somewhat less than the legal definition of crimes. However, the classifications are confused by the apparent focus on ‘the primary intent of the criminal’. For, as has already been indicated, scientific psychology moved away from attempts to infer intent over 100 years ago precisely because of the ambiguities that caused. Furthermore, the emphasis on ‘intent’ unnecessarily restricts the consideration of the psychological issues involved to the most lurid and bizarre2. The studies reported in the present volume demonstrate that the three questions outlined at the beginning of this chapter are relevant to the investigations of all crimes.

A further restriction that is commonly thought to apply to the crimes that can be ‘profiled’ is that they must be part of a series. This is somewhat akin to a psychologist saying that guidance can only be provided in the selection of a job applicant if that applicant applies for a number of jobs. Of course, the more relevant information available about a person the more effectively can inferences be drawn from that information. This is not a function of the number of crimes but of the amount of information available in total.

As can be appreciated, then, these restrictions on the possibilities for ‘psychological profiling’ are derived from the misconception that there are some special sets of skills and knowledge available only to those who have worked with criminals, or who have considerable experience of police investigations.

The following chapters provide many illustrations of how offender profiling can be seen as a natural part of the broader discipline of Investigative Psychology. As Canter and Alison have illustrated elsewhere (Canter and Alison, 1997), investigative psychology is simply a development of an existing range of psychological concepts and methodologies that may be applied to increase our understanding of offence behaviour and of the psychological processes that occur across criminal investigations.

A Hierarchy of Criminal Actions

In considering the actions of criminals the major premise for developing scientifically based profiling systems is that there are some psychologically important variations between types of crimes and also within any type of crime. This principle may be illustrated with the example of arson. In looking at the differences between crimes, are arsonists any different from any other offenders who commit crimes against property? Secondly, in considering the differences within crimes, are there differences between arsonists?

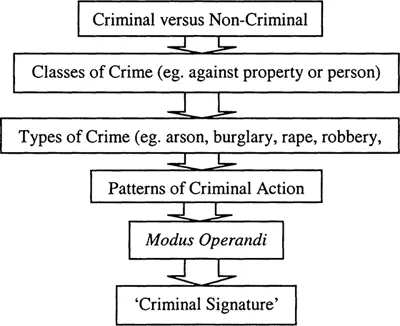

Expressed in this way it may be assumed that there are only the general questions about the differences between the types of crime and the particular questions about the differences between arsonists. But it is more productive to acknowledge that there is actually a hierarchy of possible distinctions. At the most general level there are the questions about the differences between those who commit crimes and those who do not. In contrast, at the most specific level there are questions about very particular sub-sets of activities that occur in a crime, say whether a particular type of weapon was used. Between the most general questions and the most particular are a continuum of variations that can be examined. This would include questions about different sub-sets of crimes, such as the comparison of arsonists and burglars, as well as questions about particular patterns of criminal behaviour, such as the comparison of offenders who prepare carefully in advance of a crime with those whose actions are impulsive and opportunistic.

Figure 1.1 provides notional levels in this hierarchy. However, the linear ordering of this table is an over-simplification. The description of crimes is clearly multi-dimensional. Consider as an illustration a crime in which a house was burgled and at the same time a fire was set with material taken from the house, giving rise to the death of an occupant. Would this crime be best thought of as burglary, arson or murder? The charge made against the accused is usually for the most serious crime, but psychologically that may not be the most significant aspect of the offender’s actions. The difference between an offender who came prepared to set fire and one who just grabbed what was available may be crucial. The murder may have been an accident or unfortunate coincidence. One central research question, then, is to identify the behaviourally important facets of offences. Those facets that are of most use in revealing the salient psychological processes inherent in the offence are often also of value to help answer questions posed by the investigators.

Figure 1.1: A Hierarchy for the Differentiation of Offenders

The Radex Model - Beyond ‘Types’

There is one particularly important implication of the hierarchy of criminal actions. This is the challenge it presents to the notion of a criminal ‘type’. There are some aspects of a criminal’s activities that are similar across many other offenders. These lie at the most general end of the ‘hierarchy’. They involve the actions that define the individual as criminal. But there will be other actions that s/he engages in that are located further towards the specific end, the activities that identify a particular crime. Furthermore, some of the actions will overlap with those of other offenders, for example whether s/he carries out his/her crimes on impulse or plans them carefully. Indeed there will be relatively few aspects of his/her offending, if any, that are unique to him/her (these are known as ‘signature’). Even those may not be apparent in all the crimes that s/he commits.

The actions of any individual criminal may therefore be thought of as a sub-set of all the possible activities of all criminals. Some of this sub-set overlaps with the sub-sets of many other criminals, and some with relatively few. It therefore follows that assigning criminals to one of a limited number of ‘types’ of criminal will always be a gross oversimplification. It will also be highly problematic to determine what ‘type’ they belong to. If the general characteristics of criminals are used for assigning them to ‘types’ then most criminals will be very similar and there will be few types. But if more specific features are selected then the same criminals, regarded as similar by general criteria, will be regarded as different when considered in relation to more specific criteria.

This is the same problem that personality psychologists have struggled with throughout ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Profiling Property Crimes

- 2 Intruders, Pilferers, Raiders and Invaders: The Interpersonal Dimension of Burglary

- 3 The Criminal Range of Small-Town Burglars

- 4 Bandits, Cowboys and Robin’s Men: The Facets of Armed Robbery

- 5 Criminal Weapon Use in Brazil: A Psychological Analysis

- 6 The Contribution of Psychological Research to Arson Investigation

- 7 Theft at Work

- 8 The Psychology of Fraud

- 9 Statistical Approaches to Offender Profiling

- 10 Using Corporate Data to Combat Crime against Organisations: A Review of the Issues

- 11 Crime Analysis: Principles for Analysing Everyday Serial Crime

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Profiling Property Crimes by David V. Canter,Laurence J. Alison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.