![]()

Part I

The US, the UN, and the Syrian conflict

The role of religion and the dictator/democracy dilemma

![]()

1

The history of US–Syrian relations

The role of Bashar al-Assad

A Syrian videographer, Adam Hussein records from a rooftop in Syria what initially caused him to start filming on April 4, 2017. He starts with a pan of the city of Khan Sheikhoun, Syria. It shows plumes of smoke following bombs that had been dropped from Syrian aircraft. But the plumes of smoke don’t dissipate like they usually do. The smoke spreads out like a cloud of mist hanging in the air on a summer morning over the San Francisco Bay. But these are more yellow in color and don’t burn off as the sun rises. He leaves his rooftop to get a closer look. He records a series of bodies lying in the mud. Then adults gasping for breath. Then children, one after another, doing the same. Some footage shows close-ups of children foaming at the mouth. Then shots of the hospital where he records scene after scene of gas victims, some children being taken in by a brother or a neighbor. Then scenes of patients of all ages, lying on stretchers. Then shrieks of grief from arriving family members.1

Clarissa Ward, for CNN, compiles other videos collected from those who witnessed what was going on. If this were a courtroom, her video would serve as an opening statement of proof in a case of the Syrian government’s commission of war crimes on its own citizens. Here, the proof is compiled, complete with footage of families who bear witness to what had happened to their children, including footage of their sorrow and grief at the time of burial.2

How can this happen in 2017? How can it be allowed to happen? What role should the US play in stopping war crimes from happening? What role the does the UN play in US foreign policy decisions? To answer these questions, we need to take a close look at the Syrian civil war. We need to look at Bashar al-Assad, the president of Syria, and ask about his responsibility for what is happening there. What were the signals he gave that he might resort to war crimes, and how did the US react to these signals?

We next need to look at the US and its foreign policy, and what responsibility it bears for not preventing these atrocities. How has the US played a role in bringing about the situation in Syria? We will start by looking at Syria as a part of general US foreign policy in the Middle East following World War II. Then we will focus on the Obama administration, and the president, in particular, for keys to his reasoning to act or fail to act in Syria.

After all, the civil war has been going on since 2011. In a country of more than 20 million people, there has already been a displacement of close to 11 million of its citizens. Over 4 million are UN-registered refugees. Close to 500,000 Syrians have already died in the civil war. Thousands have been tortured. Fifty thousand have disappeared in Syrian prisons, with no word of their whereabouts. There has also been proof of earlier use of chemical weapons.3 So why have the US and the UN been so slow to act? We will use the democracy and rule of law versus dictatorship dichotomies and the US’s own ambivalence towards how important democracy really is to foreign policy as a lens through which to exam both presidents and their decisions concerning Syria. I will also describe the role that religious belief has in shaping individual decision-making of the various leaders. I will argue that religious belief can be used rather cynically to generate support from a particular political base or enlist the help of allies. It can also be used as an incentive to name parties in a conflict as evil and then justify the use of force, even brutal force, against the created backdrop of an apocalyptic battle between good and evil. Another way of using religious belief is found in Obama’s decisions. As opposed to emboldening action, his belief in the evil of the world was turned internally as well as externally. It may have caused him to isolate Assad but then also caused a paralysis in the use of force that contributed to the rise of ISIS to Assad’s later turning to Russia and to Assad’s second use of chemical weapons and may have also contributed to the refugee crisis. These all made President Obama turn back to Congress for authority to use military force. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. We first need to look at Assad.

One narrative that tells how the US came to confront the dictator versus democracy dilemma starts in March 2011.

Bashar al-Assad’s responsibility for committing war crimes. Ascribing intent from actions

As in any criminal case, one of the most difficult issues is determining the intent of the actor. For a jury to determine, absent a voluntary confession from the defendant that he killed the victim, whether the defendant acted with the requisite intent (that the actor was not insane and knew the consequences of his actions, that those actions were wrong, and that he was not under a reasonable belief that a threat to his own life or to the lives of his loved ones or his charges was in progress), the jury learns that it must determine which intent was primary from among a number of possible intentions or motivations. Perhaps the defendant was driven to act because of the way he was raised. Perhaps the defendant came to believe his life was threatened, by earlier experiences he had, that may have made him paranoid, or unreasonable in his conviction of what was required of him when facing a particular threat.

What the jury quickly comes to see in determining what a person’s intent is at any given time is a historical reconstruction. Why did the defendant order the bombing? Was he righteously angry, feeling desperate, sad, in the fog of war, with a memory ripe in his mind of what had happened to a close friend or loved one, or was he acting as a result of what he had been taught, despite perhaps not even remembering who had taught him or when. He may defend himself by saying he was acting instinctively, from the very code of his being – whether learned on the street, on the battlefield, in the mosque, or in the classroom. In so acting he was foundationalist in his ethics, believing he had no choice because to not so act would violate his sense of himself, or his identity.

The jury is told, nonetheless, to make a determination about what the actor’s main, sole, major purpose or intent had been. And as counselors at law know, sometimes, when confronted with a set of events and circumstances, the actor may come to a realization of what his or her intent had really been. The actor may become all the more determined that he did not have criminal intent. On the other hand, some actors may have enough self-awareness to realize that they did have criminal intent and must take responsibility for their actions. We will return to this latter point in the chapter on Truth and Reconciliation and forgiveness.

In the court of international public opinion, the issues are basically the same. Historical facts can serve as a means to make a determination of what may have been going on in the actor’s mind when they made the decisions they made.

My method then will be to list the facts on a timeline and then “mind the gaps.” This method is familiar to litigators as it opens up the past events to possible competing narratives. It is in the process of examining the competing narratives, of comparing what we know and what we don’t know, what is usually done, and what was done in this case, and what was not done, after the event in question, that one can come to a more nuanced understanding of events in question. The judgment of what it means is more informed. We start our case for what happened in Syria with the case for and against Assad, recognizing that, without a confession, our task is a reconstruction based on circumstantial evidence. Still our case may hold up in the court of history and public opinion.

The case against Assad

The whole situation seemingly could have been avoided if Assad and his regime had not made a series of repressive choices that would lead to international condemnation. The civil war seemed to start from an overreaction to a rather benign protest. In March 2011, protests erupted in the city of Daraa when a group of boys were accused of painting anti-government graffiti on the walls of their school. Assad’s security forces chose to move in and detain the boys. The boys’ release was sought by their parents, and they were joined in a demonstration on March 15, 2011, held in the capital. The protest took place in Damascus’s Old City. On March 18, back in Daraa, security forces opened fire on a gathering of protesters, killing four people. It is easy to see how supporters of the democracy movement would use these killings to drum up support for more demonstrations. As the word spread so did the protests.

Rather than see these demonstrations as ways for protestors to make their voices heard, Bashar al-Assad instead chose to crack down on any demonstrations against the government.

To understand Bashar al-Assad (the son’s) reaction to these events, one first needs to understand the history of Syria and then a history of his father.

Alawites and religious tension within Syria4

Many non-Muslims know that there is a religious divide between Shia and Sunnis. Fewer understand the long-standing distrust between Sunnis and Alawites in Syria. Alawites (once known as Nusayris) believe in the divinity of Ali, Mohammad’s cousin and son-in-law, and so line up more with the Shia than the Sunni. They share in centuries of oppression by Sunnis who believe that such belief makes them infidels.5

After centuries of oppression, Alawites became an insular community. One custom in particular reinforced this isolation, namely that of endogamous marriage, according to which the children of unions between Alawites and non-Alawites cannot be initiated into the Alawite community. As one might imagine this causes two key characteristics: a sense of separateness and a disdain for the “Other.”

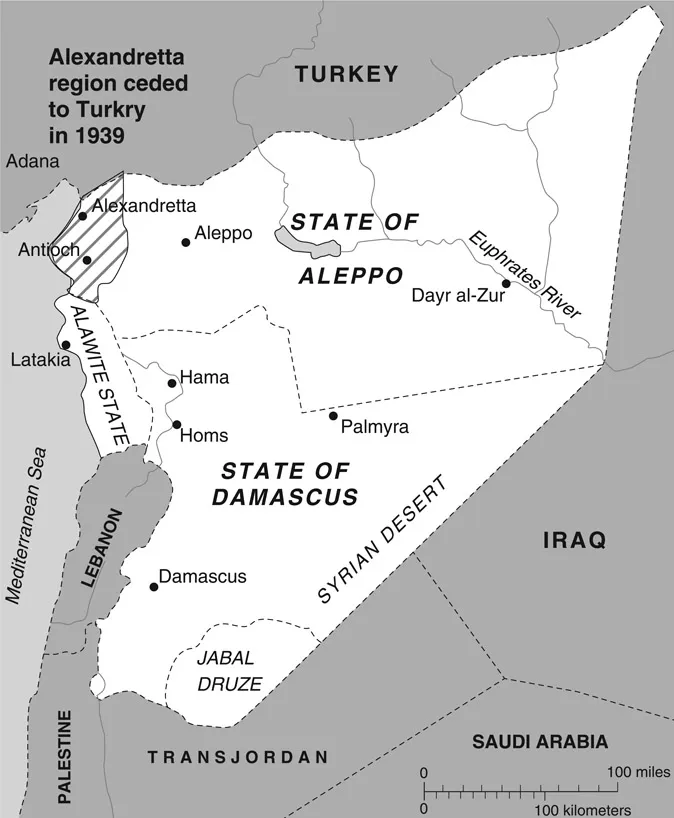

The French, who administered Syria after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, initially provided Alawites with their own state. The French encountered hostility to their rule from the Sunni majority and so encouraged an integration of Alawites and Sunnis, especially through service in the military. The following map (Figure 1.1) shows where the Alawites were congregated during the 20s and 30s.

The division of Syria under French administration in the 1920s

Joshua Landis, a professor of Middle East studies at the University of Oklahoma, explained in a blog post about the Alawites in June 2011:

There was considerable tension within the Alawi community over the notion of unity with Syria in 1936, which was mandated by the Franco-Syrian treaty of that year. Part of this tension was the fear that Sunnis would discriminate against Alawis in their courts, as had happened in the past. Under Ottoman law, Alawis were refused the right to give testimony in court because they were not considered to be Muslims or People of the Book.6

Evidence that this distrust of the Alawites for Sunnis in 1936 had an impact on how Syria would later be governed comes from a letter written by an Alawite to the then Jewish prime minister of France, Leon Blum. The letter emphasized an Alawite objection not just to Sunnis but to Islam generally, as well as the years of oppression the Alawite community has experienced as a minority community. The Alawites wanted guarantees from the French that they would be protected from oppression. Eventually this would lead to the Alawites being seen as a group that was more secular and more neutral than other Muslim groups in Syria. Still, as we will see later, in the emergence of ISIS Assad would see a Sunni backing. This attitude would also lump other rebel groups as associated with Sunnis (backed by Saudi Arabia) and see the terrorist threat as connected to an attempt by Sunnis to return to its repressive majority status. Alawites would see a threat in Sunnis should they ever lose their ruling status in Syria.7

Figure 1.1 Syria Before World War II

In the lead-up to World War II, after their plea to the French prime minister failed to stop plans to integrate the Alawite state into Syria, some Alawites tried a new tactic. They urged assimilation with Shiites in order to gain the protections of a larger minority group. Alawite religious leaders published a number of tracts declaring that Alawites were Shiites and that any Alawite “who did not recognize Islam as his religion and the Koran as his holy book” would not be considered a member of the sect.

Next for our discussion is to place Israel into our understanding of Syria foreign policy. Part of Syria’s understanding of itself is not only its colonialist past but also the rise in pan-Arabism in response to what it saw was the West’s support of Israel. Key to this history is Syria’s 1967 war with Israel. Before the start of the 1967 war, attacks conducted against Israel by fledgling Palestinian guerrilla groups were based in Syria, as well as Lebanon and Jordan. These attacks had increased, leading to a strong response from Israel. In November 1966 an Israeli strike on the village of Al-Samū in the Jordanian West Bank left 18 dead and 54 wounded, and, during an air battle with Syria in April 1967, the Israeli air force shot down six Syrian MiG fighter jets. In addition, Soviet intelligence reports in May indicated that Israel was planning a campaign against Syria, and, although inaccurate, the information further heightened tensions between Israel and its Arab neighbors.

Syria had earlier criticized Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser for Egypt’s failure to aid Syria and Jordan against Israel. Syria also complained that Egypt was excusing its lack of involvement in relying on the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) stationed at Egypt’s border with Israel in the Sinai. Already the UN was being portrayed as a tool of the US and its interests in Israel.

Perhaps, to show himself no tool of the UN, on May 14, 1967, Nasser mobilized Egyptian forces in the Sinai, and on May 18 he formally requested the removal of the UNEF stationed there. Four days later he instituted a blockade, closing the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping. The result was to endanger the port city of Elat in southern Israel. Jordan then escalated the situation when on 30 May 1967, King Ḥussein of Jordan went to Cairo to sign a mutual defense pact with Egypt, placing Jordanian forces under Egyptian command. Iraq, Syria, Egypt and Jordan all joined forces together.

Early on the morning of June 5, Israel responded. It staged a sudden preemptive air assault against Egypt that destroying more than 90 percent Egypt’s air force before it could leave the runway. A similar air assault incapacitated the Syrian air force. Without cover from the air, the Egyptian army was left vulnerable to attack. Within three days the Israelis had achieved an overwhelming victory on the ground, capturing the Gaza Strip and all of the Sinai Peninsula up to the east bank of the Suez Canal.

Jordan honored its commitment to the alliance the same day, commencing an artillery barrage aimed at West Jerusalem. Israel responded with a counterattack – disregarding Israel’s warning to King Ḥussein to keep Jordan out of the fight. Already by June 7, Israeli forces had driven Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank.

The UN Security Council called for a ceasefire on June 7 that was immediately accepted by Israel and Jordan. Egypt accepted the following day. Syria held out, however, and continued to shell villages in northern Israel. On June 9 Israel launched an assault on the fortified Golan Heights, capturing it from Syrian forces after a day of heavy fighting. Syria accepted the ceasefire on June 10.

The Arab countries’ losses were both humiliating and devastating. Egypt’s casualties numbered more than 11,000, with 6,000 for Jordan and 1,000 for Syria, compared with only 700 for Israel. The Arab armies also suffered crippling losses of weaponry and equipment. The lopsidedness of the defeat demoralized both the Arab public and the political elite. Nasser announced his resignation on June 9 but quickly yielded to mass demonstrations calling for him to remain in office. In Israel, which had proved beyond question that it was the region’s preeminent military power, there were celebrations. Some in Isra...