- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

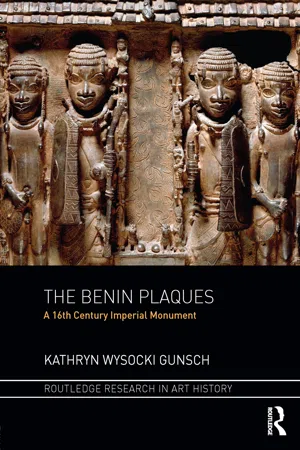

About this book

The 16th century bronze plaques from the kingdom of Benin are among the most recognized masterpieces of African art, and yet many details of their commission and installation in the palace in Benin City, Nigeria, are little understood. The Benin Plaques, A 16th Century Imperial Monument is a detailed analysis of a corpus of nearly 850 bronze plaques that were installed in the court of the Benin kingdom at the moment of its greatest political power and geographic reach. By examining European accounts, Benin oral histories, and the physical evidence of the extant plaques, Gunsch is the first to propose an installation pattern for the series.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Benin Plaques by Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

These Benin works stand among the highest heights of European casting. Benvenuto Cellini could not have made a better cast himself, nor anyone before or after him, even to the present day. These bronzes reach the very heights of what is technically possible.

—Felix von Luschan, Die Alterthümer von Benin, 1919

The Benin kingdom’s art has inspired frank admiration for centuries in what is now Nigeria and around the globe. Benin art presents a powerful court in ivory and bronze, testifying to the kings’ military might, royal splendor and international connections. Since 1897, when British soldiers seized part of the royal collection and sold it at auction, the finely carved ivories and detailed bronzes were almost immediately apprehended as fine art in Europe and America. As a result, these artworks are now dispersed around the world. The battle in Benin City in 1897 marked a tragic end to the Benin court’s political autonomy, and the repatriation of the kingdom’s cultural patrimony is a question of active debate today. By scattering the Benin bronzes throughout the world, history has prevented members of the court and the scholarly community in Nigeria and elsewhere from studying and understanding the most singular artwork within the corpus: the Benin bronze plaques. This book seeks to bring the plaques together, if only in print, to visualize the majestic sixteenth-century audience hall of the Oba of Benin.

A seventeenth-century trader first recorded the presence of bronze plaques lining the pillars in the king’s audience hall in Benin City (Figure 1.1). Today, at least 850 plaques are held in European, American and Nigerian museum collections.1 The Benin bronze plaques are often considered individual artworks, but they were created and displayed as a single, monumental installation. The nature of installation art requires an examination of both the parts and the whole. Surviving examples of monumental commissions of this kind are rare in Sub-Saharan Africa, but courtly architectural programs in West Africa in more recent centuries provide useful comparisons. Viewing a single panel of King Glèlè’s nineteenth-century palace in Dahomey, in the Republic of Benin, would fail to convey the repetition and layering of iconography that establish the diplomatic priorities of his reign. Famous Yoruba court artist Olowe of Ise’s twentieth-century caryatid posts and carved doors at the Ogoga’s palace in Ikere, Nigeria, likewise function as a unified program, meant to be seen installed together. Bronze reliefs may seem discrete units that are less contingent on their placement to fully understand the patron and artist’s intentions, yet near-contemporary bronze programs in Europe illustrate the function of the parts to create a greater whole. The individual panels of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s fifteenth-century doors for the baptistery in Florence, Italy, for example, are less meaningful when separated from the entire installation. What the artist has included—and, as importantly, omitted—builds a comprehensive program that envelops each individual work and sheds light on the political, social and religious contexts for the commission as a whole.

Figure 1.1 British Museum plaque Af1898,0115.46, Four pages in front of the palace.

Source: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

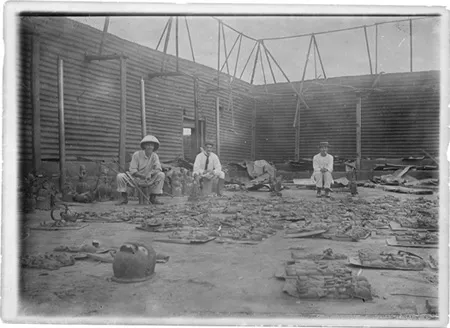

That the Benin plaques have not been studied as a single unit may be tied to their discovery as individual pieces arranged in a storeroom when the British invaded the palace in 1897 (Figure 1.2). Since 1897, scholars have known that the plaques were once installed, but had not themselves encountered the plaques as a complete decorative program. Even if the de-installed plaques were kept in their original order in the storeroom, the British soldiers did not record their placement. After the violence of the 1897 siege and subsequent interregnum, Benin court historians have no detailed description of the plaques’ original display. Anthropologists and ethnographers were the first to study and write about the plaque corpus, and their interests centered on the clothing, weapons and other material culture depicted in the various compositions, not the artworks themselves. Once art historians began to consider these objects, the plaques were dispersed into far-flung collections, making the study of the entire series impractical.

Figure 1.2 ‘Interior of the royal palace, destroyed in a fire, bronzes on the ground. Capt. C.H.P. Carter 42nd, E.P. Hill.’ Unknown photographer, Benin City 1897. Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, PRM 1998.208.15.11.

Source: © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

The failure to study the Benin plaques a monumental installation has prevented the analysis of patterns within the corpus. When viewed together, it is possible to notice the relevance of ornamental motifs, and the presence of pairs and series. The structural function of repeated gestures and highly ordered compositions also comes into focus. The variations in technical mastery between plaques no longer seem to be the idiosyncrasies of different artists, but rather an argument for increasing sophistication over generations of practice. The subtle physical signs of facture point at systematic production methods when observed in a large group. The panoply of courtiers and warriors, bewildering when encountered as a small subset of the work, can be placed into meaningful hierarchies. The recursion of particular activities throughout sections of the corpus suggests that the meaning of the whole might be within reach.

In the following chapters, I combine my observations on the known plaque corpus with historical accounts to develop a hypothetical proposal for their precise dating, patronage, methods of production, and organization within the audience court. Nearly five centuries after the plaque commission, this book is an effort to fully examine one of the greatest courtly artworks of the sixteenth century—and is an invitation to a renewed debate on the meaning and function of the corpus.

A brief history of the plaques

The reigning Oba, or king, His Royal Highness Ewuare II (reigning since 2016) traces his ancestry to the second Benin dynasty founded in approximately 1300 A.D. In the late fifteenth century, his ancestor Ozolua the Conqueror (reigned c. 1480s to 1516 or 1517) had expanded the Benin kingdom to the north by conquering the Esan peoples and to the west by challenging the powerful Yoruba city of Ijebu-Ode.2 By the end of the fifteenth century, Ozolua also maintained dominance over the contemporary kingdoms of Udo, Oyo, and Owo. Ozolua’s territorial expansion efforts raised Benin to the level of a regional power, and tributes exacted from conquered territories provided riches to the court in Benin City. By the time that Ozolua’s grandson, Oba Orhogbua (reigned c. 1550s–1570s), conquered and founded Lagos, the kingdom dominated important rivers and coastal ports within their significant new territory. At the peak of its power in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the kingdom of Benin reached from the River Niger to the coast and the kingdom of Dahomey, and included approximately one million subjects.3 The plaques are traditionally dated to this period of wealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, partially due to the sudden lavish expenditure on art required to produce the corpus.

The assembled plaques cover more than 1,130 square feet; there were at least 850 extant plaques in the full corpus, which can be grouped into two size categories: wide (approximately 30–40 cm wide) and narrow (approximately 19 cm wide). Both types are between 40 and 56 cm tall, but only the wide plaques have small perpendicular flanges on the left and right sides. The plaques are made of brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) and bronze (an alloy of copper and tin), but are primarily referred to as “bronzes” in the literature, a tradition continued here. The majority of the compositions portray figures standing alone, in pairs, or in groups of three. A large subset of the plaques depicts simple decorative motifs, such as leopards, fish, or crocodiles. A smaller subset presents five or more figures in complex tableaux of battle scenes or processions. Nearly all the plaques share a similar foliate background pattern, and many include decorative bosses, rosettes, or crescents in the corners of the composition. The sheer number of plaques and the immense size of the assemblage must have been impressive for local courtiers, foreign ambassadors, and traders alike. The Benin bronze plaques are now dispersed in museum collections around the world, with the majority of the corpus held in the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum, the British Museum, the National Museum of Nigeria in Lagos and Benin City, the Weltmuseum Wien, the Field Museum of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The first known reference to the plaques was published by Olfert Dapper, a Dutch doctor and amateur historian who wrote about Benin in his 1668 publication, Naukeurige Beschrijvingen der Afrikaensche gewesten:

It [the king’s court] contains beautiful long square galleries about as big as the exchange at Amsterdam, some bigger than others, resting on wooden pillars, covered from top to bottom with cast copper, on which deeds of war and battle scenes are carved. These are kept very clean.4

Dapper did not visit Benin himself; this passage was likely provided by Samuel Bloemmaert, the head of a trading company who based his reports on information provided by an employee in Benin.5 Dapper/Bloemmaert’s statements about the plaques are slightly incorrect. They are cast, not carved, and made of brass and bronze, not copper; they include more than “deeds of war and battle scenes.” However, this testimony is the first record of the plaques’ existence and the only contemporary record of their installation within the Oba’s court. David von Nyendael, a subsequent visitor to the Benin court who wrote a detailed account of the palace in 1702, failed to mention the plaques, and so it is generally accepted that the plaques were removed before his visit.

Other visitors made no mention of the plaques until the late nineteenth century. During the period of British occupation in 1897, Ernest Roupell, the British District Administrator, interviewed elders and remaining court officials about the history of the kingdom. Roupell’s informants stated that the plaques were commissioned by Oba Esigie (reigned c. 1517–1550s) and his son. In their account, a white man named Ahammangiwa came with the Portuguese during Esigie’s reign and made plaques and bronze works for the king.6 Esigie then gave Ahammangiwa young boys to teach because he had no children of his own.7 After Oba Orhogbua’s accession to the throne, the king killed a neighboring ruler in retaliation for killing Benin messengers. According to the courtiers, Ahammangiwa was still alive at the time, and the new Oba commissioned him to commemorate the event in bronze so that he could hang the depiction on the “walls of his house.”8

Roupell’s interviews are often disregarded in the literature on Benin,9 but they represent the first recorded account of the plaques’ history from members of the Benin court. Roupell was an occupier speaking only with the members of the court who had not fled or been killed during the war and its aftermath. His account must therefore be approached with some skepticism, but it cannot be dismissed. Jacob Egharevba recorded and published the court’s oral history in successive editions of his books Ekhere Vb’Itan Edo, published in 1933, and A Short History of Benin, published in 1936. Egharevba’s books are strangely silent on the history of the plaques, perhaps suggesting that by their publication the courtiers could not agree on the history of the plaque corpus. Egharevba does not include any part of the account given by the courtiers to Roupell in 1897. He instead recorded that Oba Oguola (reigned c. 1280) introduced casting to the Benin court, although Egharevba’s contemporaries felt that bronze-casting had existed much earlier.10 Egharevba stressed that Oguola commissioned bronze works “for the preservation of the records of events,”11 which echoes the purpose of the plaque corpus. He does not mention bronze-casting again until the reign of Oba Esigie; Egharevba only states that Esigie encouraged bronze-casting and that he sent a bronze cross to the king of Portugal.12 Mechthildis Ju...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A brief overview of politics, art and European contacts

- 3 Threat and creativity: the political context for Esigie’s commission

- 4 Remembrance and memorial: methods of commemorating history in Benin art

- 5 Patterns of authorship: the workshop method and architectural installation of the plaque corpus

- 6 The installation of the plaque corpus under Esigie and Orhogbua

- 7 Conclusion: a theory that covers the facts

- Annex 1: plaques by flange-pattern category

- Annex 2: flange patterns by sub-type

- Annex 3: views of reconstructed palace

- Annex 4: list of plaques by institution

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index