In the course of developing models to predict laser performance, which is the focus of this text, we often need to start at the beginning. The purpose of this chapter, then, is to provide a basic overview of processes and parameters relevant to the laser. Some readers may already be familiar with many of these concepts but may not have seen them applied specifically to laser systems.

Key concepts outlined in this chapter include an atomic view of the laser processes of emission and absorption (including the important process of stimulated emission), a basic overview of rate equations involved in various laser levels (which will be useful when developing models later), methods of pumping a laser amplifier, and the nature of gain and loss in a laser amplifier. Only the basics are presented here and many of these concepts will be expanded upon in later chapters as required.

1.1 The Laser and Laser Light

At first glance, a laser seems simple enough: an amplifier (often a glass tube filled with gas, a semiconductor diode, or a rod of glass-like material) pumped by some means, and surrounded by two mirrors—one of which is partially transmitting—from which an output beam emerges. As we shall see in this text, the arrangement is anything but haphazard.

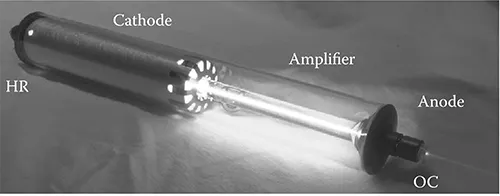

Consider first the common helium-neon (HeNe) laser, which will be one of several lasers used extensively in examples in this text. Once the most popular visible laser, it has been replaced in many applications by smaller and cheaper semiconductor diode lasers. Still, the high-quality beam lends itself well to a host of laboratory applications (and, from the standpoint of an example laser, it represents a design with very “standard” elements. The structure of a typical HeNe laser is shown in the annotated photograph of Figure 1.1.

The HeNe laser is typical of many lasers: an amplifying medium surrounded by two cavity mirrors. The actual amplifying medium, in this case, is a mixture of helium and neon gases at low pressures and excited by a high-voltage discharge. In Figure 1.1, the actual discharge is seen to be confined to a narrow tube inside the larger laser tube and occurs between the anode (on which the output coupler, or OC, from which the output beam emerges is mounted) and the cylindrical cathode. (Note that not all tubes have the OC mounted on the anode; this varies by tube and may also be on the cathode end.)

Lasers are classed by the amplifying medium employed and may use gas, liquid (dye), solid-state (i.e. glass-like crystals), or semiconductor materials. Each has a special set of characteristics and a different method of pumping energy into the system. (Most solid-state lasers, for example, are optically pumped by an intense lamp source or another laser, whereas gas lasers are usually pumped by an electrical discharge through the gas medium.).

In a practical laser, a single photon of radiation passes through the amplifier many times, with the flux of photons becoming more powerful on each pass and eventually building to power where a usable beam results. The cavity mirrors surrounding the amplifier are required to produce lasers of a manageable length. If length were not a concern one could produce a HeNe laser tube over 80m in length and forgo mirrors altogether—but this is hardly practical and the use of mirrors allows a “folding” arrangement where photons are made to pass through an amplifier many times.

The required reflectivity of the cavity mirrors depends on the gain of the amplifier employed. Low-gain amplifiers require high-reflectivity mirrors—an example being the HeNe gas laser, which commonly has a high reflector (HR) of almost 100% reflectivity and an OC of about 99% reflectivity (with 1% of the intra-cavity power exiting through this optic to become the output beam). On the other hand, higher-gain lasers optimally use lower reflectivity optics and feature a higher transmission of the output coupler. Chapters 3 and 4 address the issue of optimal coupling.

The output of a laser is quite unique, as evident from simple observation. The most important property of laser light is coherence: every photon in the beam is in phase with each other. This is a consequence of the mechanism of the laser itself, stimulated emission, which ensures that all photons produced are essentially clones of an original photon—they must therefore all be of the exact same wavelength and relative phase.

Another important property of laser light is directionality and the extraordinarily low divergence of many laser beams. This property is primarily a consequence of the arrangement of optical elements in the laser. Most lasers are standing-wave lasers which have the general form of an amplifier surrounded by two cavity mirrors aligned very parallel to each other (as we shall see later, though, this is not the only possible arrangement). Photons emitted from the front of the laser will have made many passes through the amplifier (hundreds, or perhaps thousands) and so, in order to be amplified at all they must be on a specific trajectory perfectly aligned to the optical axis of the laser. Photons that are divergent, even slightly, will often strike the side of the amplifier tube and hence never be amplified to any extent.

1.2 Atomic Processes of the Laser

In an incoherent light source, emission occurs as a result of electrons at an excited state relaxing to a lower energy level. The excitation source can be thermal, optical (absorption of a pump photon), or collision with a high-energy electron (as, for example, in a gas discharge). Once excited, atoms remain at an excited state for an average time that depends on the specific level involved (called the spontaneous lifetime), eventually falling to a lower level. The energy difference between the upper and lower levels of the transition is manifested as an emitted photon.

Incoherent light sources, then, utilize two at...