![]()

1 | Impacts of Abiotic Stresses on Growth and Development of Plants |

Muhammad Fasih Khalid , Sajjad Hussain , Shakeel Ahmad , Shaghef Ejaz , Iqra Zakir , Muhammad Arif Ali , Niaz Ahmed , and Muhammad Akbar Anjum

Contents

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Abiotic Stress and Plant Development

1.2.1 Temperature

1.2.1.1 Chilling

1.2.1.2 Freezing

1.2.1.3 Heat

1.2.2 Salinity

1.2.3 Water Stress

1.2.3.1 Drought

1.2.3.2 Flooding

1.2.4 Nutrition

1.3 Plant Development and Morphology Under Abiotic Factors

1.3.1 Germination and Seedling Emergence

1.3.2 Vegetative Growth

1.3.2.1 Leaves

1.3.2.2 Shoots

1.3.2.3 Roots

1.3.2.4 Reproductive Growth

1.4 Conclusion

References

1.1 Introduction

Plants are frequently subjected to unfavorable conditions such as abiotic stresses, which play a major part in determining their yields (Boyer, 1982) as well as in the distribution of different plants species in distinctive environments (Chaves et al., 2003). Plants can face several kinds of abiotic stresses, such as low amounts of available water, extreme temperatures, insufficient availability of soil supplements and/or increase in toxic ions, abundance of light and soil hardness, which restrict plant growth and development (Versulues et al., 2006). A plant’s ability to acclimate to diverse atmospheres is related to its adaptability and strength of photosynthetic process, in combination with other types of metabolism involved in its growth and development (Chaves et al., 2011). When plants are adapted to abiotic stresses, they activate different enzymes, complex gene interactions and crosstalk with molecular pathways (Basu, 2012; Umezawa et al., 2006).

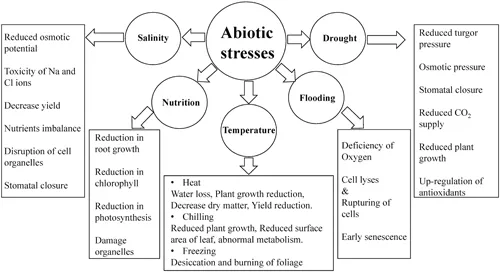

The major abiotic stresses (cold, heat, drought and salinity) negatively affect survival, yield and biomass production of crops by as much as 70% and threaten food safety around the world. Desiccation is the major factor in plant growth, development and productivity, mainly occurring due to salt, drought and heat stress (Thakur et al., 2010). When a plant is exposed to abiotic stresses, it can face a number of problems (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Effect of different abiotic stresses (salinity, nutrition, temperature, flooding and drought) on plant.

Since resistance and tolerance to this problem in plants is of great importance in nature (Collins et al., 2008), breeders face an enormous challenge in attempting to manipulate genetic modification in plants to overcome the issue. Conventional plant breeding approaches have had limited effectiveness in improving resistance and tolerance to these stresses (Flowers et al., 2000).

1.2 Abiotic Stress and Plant Development

1.2.1 Temperature

1.2.1.1 Chilling

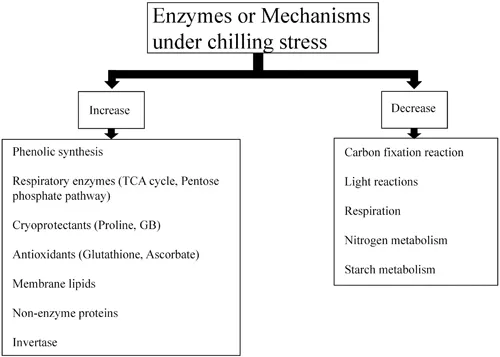

Chilling injury in plants depends on the sensitivity of their different components to low temperatures. Cellular membrane integrity is the basic component that directly relates to the plants that are sensitive to chilling stress (Levitt, 1980). Lipids present in cell membranes change their state from liquid to solid when plants are brought into light at low temperatures, which mainly depends upon the amount of unsaturated fatty acids they contain (Quinn, 1988). In order for plants to tolerate frost or chilling stress, there must be some alterations in the classes of these unsaturated fatty acids, since plants that have more fatty acids in their cell membranes can tolerate more chilling or frost stress. Different enzyme contents and activities also increase or decrease under extremely low temperatures (Figure 1.2). In plant cell membranes, several changes in physicochemical states occur that compensate for the effect of chilling or frost by increasing cell membrane permeability and also cause ionic and pH imbalance, ultimately decreasing ATP (Levitt, 1980).

FIGURE 1.2 Enzymes and mechanisms which increase or decrease under chilling stress.

1.2.1.2 Freezing

Plants significantly vary in their capacities to manage freezing temperatures. Plants grown under tropical and subtropical conditions (i.e., maize, cotton, soybean, rice, mango, tomato, etc.) are more sensitive to freezing. Plants grown in a temperate climate can tolerate low temperatures, although the degree of tolerance varies from species to species. Moreover, the extreme freezing resistance of these plants is not inherent, as at low temperatures plants activate different physiological and biochemical processes to cope with freezing in a process known as ‘cold acclimation’. For example, in one study, rye plants exposed to -5˚C without prior acclimation to cold were not able to survive, but when cold acclimatized at 2˚C for 7–14 days, they were able to survive temperatures as low as -30˚C (Fowler et al., 1977).

Previous research on cold acclimation of plants was designed to examine what happens at low temperatures, helping improve resistance under these conditions. In earlier studies, it was shown that plants activate their enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanism to cope with freezing temperatures (Levitt, 1980; Sakai & Larcher, 1987). To prevent freezing injury (cellular membrane damage) under low-temperature conditions, plants produce different osmolytes and osmoprotectants, such as lipids, proline, glycine betaine, and sugars, which help in decreasing membrane damage. Along with solutes and polypeptides, studies have shown that many genes are involved in the activation of cold acclimation processes, ultimately improving freezing resistance. For example, all the chromosomes are involved in coping with freezing injury in hexaploid wheat.

Cold acclimatization is a combination of physiological, biochemical and hereditary processes. Changes do occur in plants exposed to freezing temperatures, but it is not yet clear which changes are involved in the cold acclimation process and which are involved in other resistance processes. However, freezing-tolerance mechanisms are not related to any individual gene that copes with the freezing injury. Many efforts have been made to isolate and evaluate the genes that are induced under extremely low temperature. The latest studies confirm that ICE2 is involved in the acclimation process in Arabidopsis, ultimately increasing the tolerance of plants to low-temperature stress. The recent discovery of the CBF cold-response pathway describes the involvement of clod acclimation in resistance to low temperatures.

1.2.1.3 Heat

Plants subjected to high temperatures undergo numerous distinctive changes and adjustments. Adaptation to high temperatures occurs on diverse time scales and levels of plant organization. Exposure of plants to extremely high temperatures for long periods of time may cause severe injury, leading to death. Under such temperatures, different plant parts are affected in different ways. The nature of the injury depends on the growth stage of the plant, its susceptibility and cellular processes taking place at that time. However, in extremely high temperatures, heat not only damages the plant at a cellular level but also affects many complex processes and structures that ultimately cause death of the plant. When plants are exposed to high temperatures, several changes occur at the cellular level, including modification of lipids (which become more fluid and develop osmotic pressure) and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that disturb the cell membrane metabolism. Proteins work efficiently at a specific temperature, but when temperatures exceed their optimal zone, they are deactivated, causing changes in the activity of enzymes and increasing the production of active oxygen species (AOS) and ROS. Several enzymatic (e.g., SOD, POD, CAT) and non-enzymatic antioxidants (e.g., proline, GB) are produced to cope with ROS, but antioxidants have very little effect on the activity of AOS, which are prevalent under extremely high temperatures. The effects of AOS, including reduced photosynthesis, increased oxidative stress, and changes in movement of assimilates, significantly damage the plant and ultimately cause its death (Hall, 2001). However, many processes and genes are involved in plant tolerance under heat stress. Commonly, under field conditions, plants are exposed to heat with a combination of other stresses, such as heat and drought stress or heat and radiation stress. Similar damage may occur via other stresses when combined with heat stress. Plants respond to different stresses in similar ways. Under heat stress, plants produce proteins to cope with the effects of high temperatures at a cellular level. These are called heat-shock proteins (HSPs; Boston et al., 1996). Different pathways are involved in mitigating heat stress in which HSPs are the only component of heat tolerance. When a plant is exposed to extremely high temperatures, different signaling genes become involved in resistance mechanisms by signaling and activating several metabolic processes. More effort is required to identify and characterize the genes that play a vital role in plant tolerance to extremely high temperatures. When the pathways involved in the resistance and tolerance of plants to heat stress are clearer, it will be easier to recognize the interaction between high-temperature stress and other stresses, which in turn will aid in devising strategies to make plants more tolerant (Nobel, 1991). The main challenge here is to recognize the cellular and metabolic pathways affected by heat stress in order to devise strategies to reduce adverse effects on crop yield.

1.2.2 Salinity

Salt stress is the major problem in arid and semiarid regions, limiting agricultural production and crop yields worldwide. About 20% of cultivated and ...