- 165 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Yakuba Gowon was born in 1934 and became Head of State in Nigeria in 1966. After successfully commanding the armed forces of the Federal Government during the Civil War 1967-70, he guided the reconstruction of the country for a further five years. He was deposed in a coup in 1975. First Published in 1987. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Yakubu Gowon by John Clarke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Early Days

Long ago, when the Sahara was green and fertile, many people came into Africa from the east in search of a new home. Among them were the Kanuri who went to the lands around Lake Chad where they settled and built up an empire. Later, a very different race, the Fulani, arrived from the west; they were the ‘red men’, cattle owners, most of whom had no settled homes, moving about continually in search of water and green grass for their beasts.

They sold milk and butter and cheese in exchange for corn to the people of the lands through which they moved and often a farmer would pay a Fulani to tether his cattle at night on a particular plot to manure it. In these ways the Fulani assisted the settled peoples but there was often friction between them: for the cattle sometimes damaged the farms and were often stolen by the villagers.

The many other people who lived in the northern parts of the country which is now Nigeria were traders and horsemen who built large markets and towns and spoke many tongues which became the language known as Hausa and whose lands are the Hausa states. They worshipped tribal gods and, although some of the Fulani became town dwellers and converts to Islam, most of the wandering herdsmen were as pagan as the settled peoples.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century there was a Fulani teacher, Othman dan Fodio, living in the northern lands to the west of the Kwara (the Niger River). He was a devout Moslem and he was appalled by what he saw of the ignorance of the people there; so he founded a school at Degel, in the kingdom of Gobir, where he trained a band of his followers to be leaders in religion and government. Within a few years, some of his pupils in the countries around had accepted his flags and had formed the Hausa states into a Fulani empire in which Islam and good government were established. He himself retired to live a life of prayer and study.

His pupils became the Fulani emirs, the kings of the Hausa states, and they paid tribute every year to Othman’s son, Bello, who had become the Sultan of Sokoto and Sarkin Mussulmi or King of the Faithful Moslems throughout the whole land. Unfortunately, the governments of the Fulani Empire established by Othman’s pupils did not follow his teaching nor maintain his standards long. The emirs of the Hausa States soon became rich, powerful and greedy. They fought each other and every year, in the dry season, sent out bands of their horsemen to raid all the smaller communities and carry off the young men and women as slaves. More and more slaves were needed to build the emirs’ palaces, to work their farms and to supply their harems.

Many slaves had to be sent every year to Sokoto as part of the annual tribute to their overlord, the Sultan. The survivors of these raids fled across waterless plains or up into the hills of the Bauchi plateau. There they were safe but they lived in very hard conditions; materials for building were so scarce that their houses were small; their crops of grain could be grown only in tiny plots among the rocks; they could neither grow nor buy cotton and had to use grass and goatskins for their clothing and they were often short of water.

However, from their hillside hideouts they often launched successful counter-attacks against their Moslem enemies when they were seen approaching; for the horses raised clouds of dust in the plains below. The hill-men waited and when the slave raiders began to ascend the slopes, rolled down rocks on them, stampeding the horses and killing their riders with spears and poisoned arrows. Thus it was that the hill-men of the Bauchi Plateau were the only peoples of the whole area who were not totally subjugated by the Fulani.

In the early days of this century when the Hausa States had accepted the rule of British administrators and had been forced to give up slave raiding, the hill people still maintained their isolation; they distrusted all strangers and attacked the first British officers who tried to persuade them that they could now safely come down and live on the more fertile lands below.

Because the Plateau had been the home of pagan communities defending themselves against the Moslem slave raiders, it was decided by the British administration that it should be an area open to Christian missionaries, the earliest of whom were members of the Church Missionary Society - men and women who had studied at British universities and who were sometimes related to the leaders in the anti-slavery movement. Some had had hospital training and worked as much needed medical missionaries but they had a hard task.

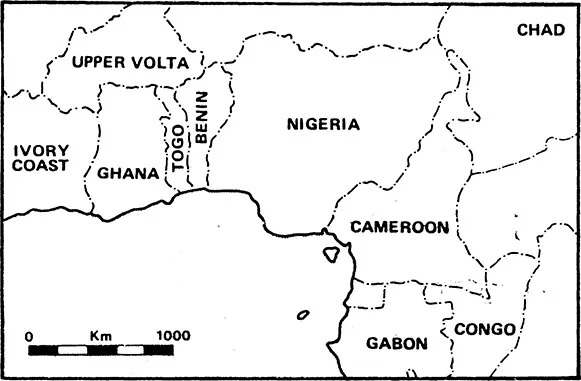

Map 1 Nigeria and its neighbours

The hill people on the Plateau were suspicious of all strangers and did not want even to talk to these white men who had come to live among them. The missionaries would build a small church where they sat together to pray and sing hymns and they had medicines for the treatment of some of the great ills which troubled the people - malaria, leprosy and sleeping sickness. So, in time, the villagers began to feel that these white men and women might be harmless. When the missionaries offered to teach the village children to read and write, the elders allowed a few of their boys to go and look at the books when they were not required for work on the farms or for other village activities. Thus it happened that somewhere about the year 1910, the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) started a mission and a school at Tuwan, near Kabwir and some fourteen miles from Pankshin at the southern end of the Plateau. The people who lived at Tuwan were Angas, they claimed that they and the Kanuri were blood brothers (kaka) with whom there could never be any quarrels. They were one of the largest of the hill communities and were good farmers, the owners of cattle and goats and the makers of iron tools.

A young man named Gowon, the son of Godwan, the Rainmaker, of Lur, had come to the mission at Tuwan and was persuaded by the words and good works of the missionaries to become a Christian. He was baptised and named Yohanna. This was a brave step for young Gowon to take for he was born a member of a ruling family of the Angas; in due course he might well have become the chief of his people, an important person among all the Angas of the Plateau.

To make the change from one of the traditional religions to that of the European missionaries was very difficult, for the power of the old men in African society was in those days strong. So strong that, to some of the young men and women, their old religion may often have seemed to be a barely tolerable curb on their initiative and enterprise. Their religion was in the hands of elders who feared new ideas, so a new religion which spoke of a loving God and the forgiveness of sins was a great attraction to the young. Even their fathers, who might disown any of their children who would turn to the new religion, could see that the missionaries were men and women who practised the good works which they preached.

So Gowon of Lur and his brother Darshua made the great decision. They gave up the rights and properties which they held under the old religion and entered into the strange new world of the Christians. He was baptised in the early years of this century; the sign of the cross was made on his forehead by a finger dipped in Holy Water. He was taught to read and write in Hausa and after some years became a Catechist, that is a person authorised to read the Bible and the prayers of the church in public; he became a lay-reader for the Church Missionary Society on the Plateau.

As a responsible leader of the Christians, Yohanna Gowon set an example to all members of his community as a good farmer and as the father of a healthy, well-behaved young family. His wife, Saraya Kuryan, daughter of Goar, came of a good Christian family highly respected by the Angas people. She and her husband had been married for some years and had two sons and two daughters already growing up when their son Yakubu was born in 1934. They could not have imagined the changes which were to take place in the world in which he was to live nor the place to which he would rise in it. They knew that, for the past thirty years, British officers had been bringing together the many peoples who lived on the lands bordering the great Niger River and had set up a colonial state which had already begun to be called Nigeria. These things meant very little to them. They were mainly concerned with their own and their immediately neighbouring peoples. They could scarcely have imagined that in another thirty years, Nigeria would have become an independent nation and that their son would be a General in its Army and Nigeria’s Head of State.

Saraya, a deeply religious woman, must have prayed that her son would be worthy of her. She had been taught by the Mission how to care for her children and, as soon as custom permitted, she placed Yakubu on her back and tied him to her body with a strong cotton wrapper for his safety and her own convenience. Only so could she know at all times where he was and only thus when she heard his little cries for the breast, could she so conveniently slip him round under her arm to satisfy his needs.

As he grew and began to walk she would at times loosen the cloth and set him down on the ground to toddle around her as she sat weaving or talking to her friends. Sometimes he would be fast asleep on her back as she was striding home from a market with all her purchases in a reed basket on her head. He would sleep soundly on her back, as in a rocking chair, when she prepared corn for the evening meal, pushing her hands on the grindstone steadily to and fro. A quiet, happy life for a fortunate small boy.

Yakubu’s earliest memories are of playing with his sister, Maryamu, having lots of fun with her, teasing her, sometimes bullying her and making her cry and in turn being beaten by their elder sister as a punishment, after which they were all loving friends again. He chattered in Angas, his mother tongue, and in Fulani, using words picked up from the young women who brought milk into the village whenever there was a cattle camp near by. Yakubu would run along beside them as they came striding towards their home, laughing and singing, carrying the large bowls of fresh and soured milk on their heads. As he ran, trying to talk to these gaily dressed girls, he would be followed by his special pet, a large black puppy which became his inseparable companion and protector. One day his sister sat herself in a large basket on a raised platform in the front porch of their home. She rocked it about pretending to be driving a motor car, a new wonder which had appeared on the rough roads near the village. Yakubu pulled her out of the basket and jumped into it himself, rocking it so violently to show its speed that the ‘car’ overturned. He was thrown out and fell head first onto a small fire. He still has a scar on his forehead to remind him of the burn he suffered that day. He was taken crying to the mission dispensary where the wound was treated and then his naughty behaviour was surprisingly rewarded with a piece of cake. He says that he vividly remembers seeing the white icing through his tears.

One of the leading members of the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) in Northern Nigeria in the nineteen-twenties was Dr. Walter Miller. He was a forceful person who did not agree that the missions were bound to accept the pact which Colonel Lugard, British High Commissioner, had made with the Moslem Emirs in 1900 which permitted the missionaries to work only in the non-Moslem parts of the country. He claimed that the Christian Church was bound to preach its good news everywhere.

Dr. Miller spoke Hausa fluently and, being a medical man, was widely respected as a healer of the sick. He became friendly with the Emir of Zaria, the ruler of one of the larger of the Moslem Emirates, and persuaded him to allow the Mission to build a hospital, a school and a church in Zaria city, close to the palace of the Emir. Later, in 1929, the Mission moved to a site just outside the walls of Zaria at Wusasa.

Thus, it happened that when the large mission station was built at Zaria, the C.M.S. handed over its work on the Plateau, including the Angas lands, to the Sudan United Mission. So Yakubu Gowon’s father Mallam Yohanna Gowon and the Christian community at Tuwan became members of this new mission. That may not at first have seemed to be a very great change. The two missions preached the same religion and the Christians in Tuwan used the same little school and church but there were differences and his father was unhappy. He felt that the aim now was only to teach converts to read the Bible, whereas the C.M.S. missionaries had laboured to teach them to understand the Christian religion and to introduce them to higher education.

A friend, Bishop Alfred Smith, suggested to Yakubu’s father than he and his family should leave the Plateau and go down to the C.M.S. mission at Zaria. It was pointed out to him that he would be working with old friends and his children would have the benefit of all the schools there. So, in due course Mallam Yohanna Gowon decided to leave the Plateau with his family and go down to make a new home in Wusasa.

It was almost as big a change in his life as had happened when he became a convert to Christianity. Now he was leaving his birthplace, leaving all his kinsmen, the people who spoke his mother tongue and all the customs which he had known since his earliest days. He was going down from the cool air of the Plateau to the heat of the Zaria plains where he would be among strangers. If he and his wife were sorry to be quitting their home and perhaps uncertain about the future, their doubts and fears were nothing to the sadness of their children leaving the only home they had ever known, parting with all their friends and many of their possessions.

Yakubu well remembers the beginning of the journey along the rough red earth road and how, when they came to a stream, he was carried across the water by his mother’s younger sister. At length they reached Jos: in those days a small town on the Plateau plain at the head of the narrow-gauge railway, which had been built to carry the bags of tin from the European-owned mines all the way downhill to the main railway at Zaria. This was great excitement for him and his brothers and sisters. The small engine, popularly known as ‘Dan Bauchi’, was standing in the station on two iron rails which seemed to go on and on for ever, with smoke coming out of the chimney on top and steam hissing from so many places. It was so mysterious, puzzling and frightening. They were tired, and after eating some food they settled down on the hard seats in one of the coaches of the little train. The engine blew its whistle and began to pull them along the rails. They looked out for a while at the passing Plateau lands and were soon asleep. The first chapter of their lives was closed.

M. Yohanna Gowon and his family arrived at Zaria, the end of their journey, where they were made welcome by Mallam Nuhu Bayero, who was the Sarkin Wusasa, the chief of the mission village. He was very kind and lent them a house. Then, after they had settled into their new life, Mallam Bayero marked out a plot of land for them on which to build their permanent home. Life in Wusasa was at first very strange: so hot, so noisy and everywhere so many great trees. At Tuwan all their friends had been Angas; here at Wusasa there were many differing peoples: Kanuri, Gwari, Jarawa, Nupe, Ibo, Yoruba and Hausa, each speaking their own tongue; most of them also speaking Hausa, the common language, which Yakubu quickly learned. He kept near to his father, following in his footsteps. When his father started to make a farm and later when he began to build the new home, Yakubu would offer to carry things and try to help him with his work or, if he was tired, he would sit down by his father’s cloak in the shade of a dorowa and go to sleep.

After the family had been at Wusasa for about three years, it was decided that Yakubu had grown enough and that it was time for him to enter the Infant School. There, during the first year, the boys and girls learned to put letters together to form words and were encouraged to read sentences in their ‘readers’. Yakubu was thrilled with this. It was an exciting new skill and he put his heart and mind to it and soon was surprising himself and his class teachers by his progress. The children were allowed to take their ‘readers’ home and Yakubu could always look into his father’s Hausa Bible also and practise reading it.

His success became known to one of the teachers in the Junior School, who took him into Primary Class I (Standard One) and said to the pupils there who were not learning quickly enough, ‘Listen to Yakubu! He is still in the Infant School and he did not speak Hausa when he came to Wusasa!’ He gave him the Hausa reader which was used in that primary class and Yakubu read it to the older pupils, some of whom may have been annoyed that a pupil from an infant school had been used to shame them. However, Yakubu was growing up and could look after himself.

The school had a small farm where the children grew maize, guinea corn, ground nuts, millet and sweet potatoes etc., for use in the school kitchen. It happened that there was a boy, Jonny dan Kande, whose father had land near the school farm and had planted in it a row of guava trees. They probably served as a windbreak, keeping the hot winds off the other plants on the farm but they also produced very sweet fruits. The boys stole some of them, so Jonny dan Kande decided to protect his father’s fruit. He could not fight them all at once so as Yakubu was the smallest of the boys who had stolen the fruit he began to punch him. Yakubu knew that Jonny was right but he stood up for himself; he fought back and somehow won. After this, they became the best of friends and the other boys and girls looked on them with respect.

During the following year, Yakubu went into the first of the four Junior School classes where the work was all in Hausa. He enjoyed the new things they were learning and made good progress. So much so that he and two or three other pupils were promoted by their teacher into the second Junior School class before the end of the year. In those days, the promotion from one class to another was more flexible than it is now. A bright pupil or an older one might be advanced before the end of a school year and a dull or lazy pupil was not automatically promoted if the year’s work had not been satisfactorily completed.

Unfortunately for him, Miss Locke, the Missionary who was in charge of the Junior School, came back to check the register one day and noted that ‘Yakubu Gowon’ was in the register for Class II and that she had not authorised it. She thought that he was a naughty little boy who had simply pushed himself forward. He was ordered to return to Class I. The other boys laughed at him. Feeling angry and humiliated, Yakubu turned on them and retorted ‘You may laugh but I shall catch up with you and pass you all’, which of course he did.

Looking back on his days in the Junior School, Yakubu feels that he was not an exceptionally brilliant pupil but that, without much effort, he seemed always to be near the top of the class. Unfortunately, as so often happens, such easy success arouses envy. It was perhaps inevitable, therefore, that some of his fellow pupils should gang up to disparage and bully him. This came to a head when a small group of them began to stop him on his way home and force him to take another and probably longer path. Day after day, whichever path he chose, they would be there to stop and harass him. So he decided that he had to fight them. Therefore, when they attacked him, he went for one of the bullies so violently that his surprised opponents turned and fled and they never again tried to stop him from going home by whichever path he chose. Looking back, Yakubu Gowon says:

The Wusasa Junior and Senior Schools and their pupils were fortunate for they were in the hands of well-educated missionaries with well-trained and dedicated Nigerian teachers....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Nigerian Political Terms

- 1. Early Days

- 2. Military Career

- 3. Military Coups

- 4. Gowon v Ojukwu

- 5. Civil War

- 6. Unity Assured

- Notes

- Bibliography