- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Island Of Bali

About this book

First published in 1937, Island of Bali is still regarded by many as the most authoritative text on Bali and its fascinating people. Included is a wealth of information on the daily life, art, customs and religion of this magical Island of the Gods. In the author's own words it presents a bird's-eye view of Balinese life and culture. Miguel Covarrubias, the author, was a noted painter and caricaturist as well as a student of anthropology. He lived in Bali for a total of three years in the early 1930s, and today his account is as fresh and insightful as it was when it was originally published. Introducing the island with a survey of hits history, geography and social structure, Covarrubias goes on to present a captivating picture of Balinese art, music and drama. Religion, witchcraft, death and cremation are also covered. Island of Bali will appeal to anyone with interest in this unique island, from general Eat, Pray, Love readers to serious anthropologist alike. Complementing the text are 90 drawings by Covarrubias and countless others by Balinese artists. Also included are 114 half-tone photographs, and five full-color paintings by the author.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Island Of Bali by Miguel Covarrubias in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Note on Pronunciation

THE Balinese language is a difficult one to pronounce properly; it abounds in subtle sounds – two sorts of d’s, t’s, a’s, e’s, etc. At present there is an officially recognized system, taught in Balinese schools, for the spelling of Balinese words in Latin characters. However, for English-speaking readers this system would be confusing and a few of these rules of spelling have been modified here for the sake of convenience.

In general all consonants are pronounced as in English. The Dutch dj which sounds like j in “jam” and the tj with a sound of ch as in “church” have been retained because they are nearer the Balinese pronunciation of these sounds and in order not to further confuse those accustomed to the Dutch spelling; j has been changed to y as in wayang, which is in Bali spelled wajang; nj is changed to ny—i.e., njepí: nyepí – pronounced as in “canyon.” The ng sound typical of Malay languages should be pronounced as one sound, as in “ringing” – peng’iwa and not pen’giwa.

All vowels are pronounced as in Spanish or Italian: a as in “artistic,” i as in “miss,” o as in “photo”; e, however, is short and hardly pronounced unless accented, é, è, when it is as in “egg” or “eight.” The most important modification of the Dutch spelling is that oe has been changed to u, pronounced as in “bull” or like the oo in “fool.” This is to be remembered especially in connection with geographical names as they appear in Dutch maps; for example, Kloengkoeng, Oeboed, spelled here Klungkung, Ubud.

Always in a word ending in a, this letter has a sound rather like the last a in “America,” or as in “odd.” Other phonetic signs have been omitted.

Chapter I

The Island

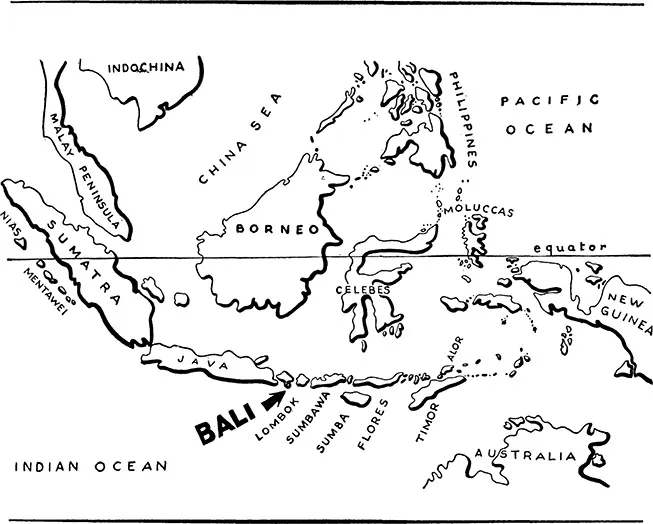

THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO lies directly on the volcanic belt of the world. Like the backbone of some restless, formidable ante-diluvian monster, more than three hundred volcanoes rise from the sea in a great chain of islands – perhaps all that remains of a continent broken up in prehistoric cataclysms – forming a continuous land bridge that links Asia with Australia. Because of its peculiar and fantastic nature, its complex variety of peoples, and its fabulous richness, the archipelago is one of the most fascinating regions of the earth. It includes famous islands like Java, Borneo, Sumatra, New Guinea, the Philippines, and the hysterical island-volcano of Krakatao. Such freaks of nature as the giant “dragon” lizards of Komodo, the coloured lakes of Flores, the orangutans, the rafflesia (a flower over three feet in diameter), and the birds of paradise, are to be found nowhere else. The population of the islands ranges from such forms of primitive humanity as the Negritos, the Papuans, the Kubus, who seem only a few steps away in the evolutionary scale from the orangutan, to the supercivilized Hindu-Javanese, who over six hundred years ago built monuments like Borobudur and Prambanan, jewels of Eastern art.

Through the centuries, civilization upon civilization from all directions has settled on the islands over the ancient megalithic cultures of the aborigines, until each island has developed an individual character, with a colourful culture, according to whether Chinese, Hindu, Malay, Polynesian, Mohammedan, or European influence has prevailed. Despite the mental isolation these differences have created, even the natives believe that the islands once formed a unified land. Raffles, in his History of Java, mentions a Javanese legend that says “the continent was split into nine parts, but when three thousand rainy seasons will have elapsed, the Eastern Islands shall again be reunited and the power of the white man shall end.”

One of the smallest, but perhaps the most extraordinary, of the islands, is the recently famous Bali – a cluster of high volcanoes, their craters studded with serene lakes set in dark forests filled with screaming monkeys. The long green slopes of the volcanoes, deeply furrowed by ravines washed out by rushing rivers full of rapids and waterfalls, drop steadily to the sea without forming lowlands. Just eight degrees south of the Equator, Bali has over two thousand square miles of extravagantly fertile lands, most of which are beautifully cultivated. Only a narrow strait, hardly two miles across, separates Bali from Java; here again the idea that the two islands were once joined and then separated is sustained by the legend of the great Javanese king who was obliged to banish his good-for-nothing son to Bali, then united to Java by a very narrow isthmus. The king accompanied his son to the narrowest point of the tongue of land; when the young prince had disappeared from sight, to further emphasize the separation, he drew a line with his finger across the sands. The waters met and Bali became an island.

The dangers lurking in the waters around the island suggest a possible reason why Bali remained obscure and unconquered until 1908. Besides the strong tidal currents and the great depths of the straits, the coasts are little indented and are constantly exposed to the full force of the monsoons; where they are not bordered by dangerous coral banks, they rise from the sea in steep cliffs. Anchorage is thus out of the question except far out to sea, and the Dutch have had to build an artificial port in Benua to afford a berth for small vessels.

One of the volcanoes, the Gunung Batur (5,633 feet), is still active. In the centre of the old crater an enormous amphitheatre ten miles across by a mile in depth rises like a dark blister, the smoking cone of a more recent crater (see map), its sides covered with the black lava spilled out into the great bowl of the older crater in the latest eruption. It is said that this lava has not yet cooled deep down, and when the rain water seeps through the cracks it turns into clouds of steam. Half-circling the new crater is the peaceful, misty lake Batur, its shores dotted with the ancient villages of the oldest present inhabitants of the island. In former times the prosperous village of Batur rose at the foot of the volcano, but today only the villages across the crater remain, those on the safe side of the lake. One day the Batur began to growl and in 1917 it burst into a violent eruption accompanied by earthquakes. The whole of the island was affected, and 65,000 homes, 2,500 temples and 1,372 lives were lost. The lava engulfed the village of Batur, but stopped at the very gate of the temple. The villagers took the miracle as a good omen and continued to live there. In August 1926, however, a new eruption buried the sacred temple under the molten lava, this time with the loss of one life, an old woman who died of fright. The people of Batur, unable to break the spell that links their destinies to the mountain, rebuilt their village high up on the rim of the outer crater, renamed it Kububatur, and will probably remain there until again driven away by the anger of the volcano.

According to legend, Bali was originally a flat, barren island. When Java fell to the Mohammedans, the disgusted Hindu gods decided to move to Bali, but it became necessary for them to build dwelling-places high enough for their exalted rank. So they created the mountains, one for each of the cardinal points. The highest, Gunung Agung, was erected at the east, the place of honour; the Batur at the north; the Batukau at the west; and since there had to be one for the south, the raised tableland (Tafelhoek) of Bukit Petjatu became the seat of the patron of the south.1 The Batur is venerated in its neighbourhood, and the Batukau is holy to the villages on its slopes, but it is the Gunung Agung, Bali’s highest mountain (10,560 feet) that is most sacred to the whole of the island. Half-way up the mountain is the mother temple for all Bali, the great Besakih with its impressive stone gate and its hundreds of towers thatched with sugar-palm fibre. The Gunung Agung is regarded as the Navel (puséh) of the World. It is to the Balinese what Kailasa and Meru are to the Hindus of India. As Mahameru it is the Cosmic Mountain, the Father of All Humanity.

To the Balinese, Bali is the entire world. Knowledge of the other nations of which they are conscious – China, Java, and Europe – does not influence their belief in the least. They are simply other worlds that have no relation to their own conception of the earth. There is an old manuscript which gives a description of the structure of the world. Although not very highly regarded by scholars, it gives us the popular Balinese conception of the cosmos, especially as it justifies their faith that Bali is the world. The following are excerpts from a free translation:

“At the bottom of everything there is magnetic iron, but in

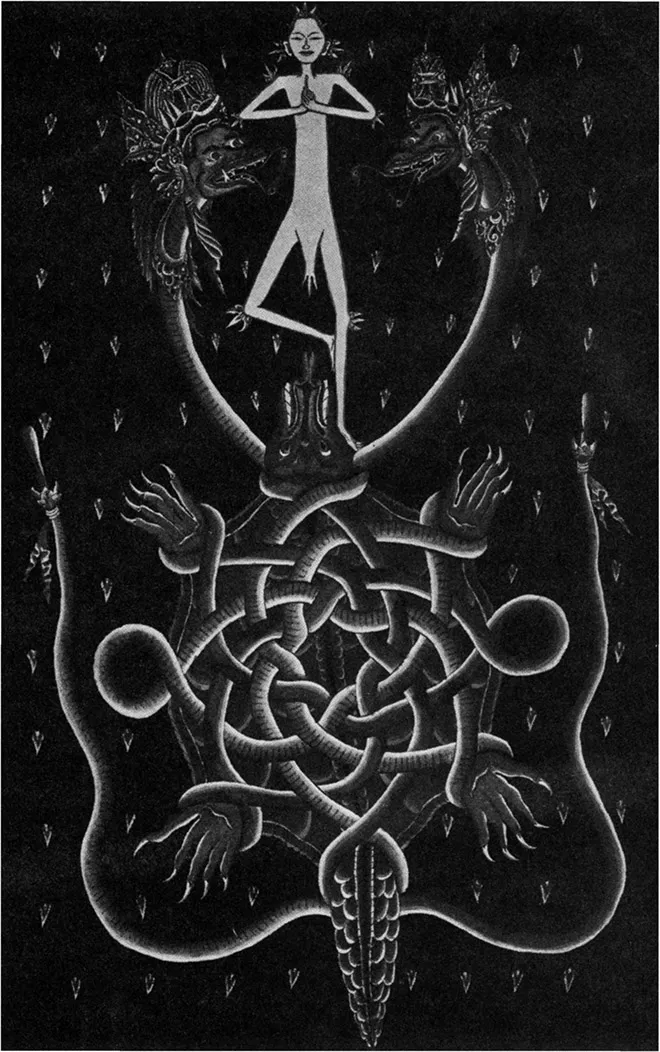

The Balinese Cosmos

The World Turtle, Bedawang, and the Supreme Being, Tintiya by Ida Bagus Togog, of Batuan

the beginning there was nothing, all was emptiness; there was only space. Before there were the heavens, there was no earth, and when there was no earth, there was no sky.… Through meditation, the world serpent Antaboga created the turtle Bedawang, on whom lie coiled two snakes as the foundation of the World. On the world turtle rests a lid, the Black Stone. There is no sun, there is no moon, there is no night in the cave below (the underside of the stone); this is the underworld, whose gods are the male Batara Kala and the female Setesuyara. There lives also the great serpent Basuki….

“Kala created the light and Mother Earth, over which extends a layer of water. Over this again are consecutive domes or skies, high and low; one of mud (which dried to become the earth and the mountains); then the ‘empty’ middle sky (the atmosphere), where Iswara dwells; above this is the floating sky, the clouds, where Semara sits, the god of love. Beyond that follows the ‘dark’ (blue) sky with the sun and the moon, the home of Surya; this is why they are above the clouds. Next is the Perfumed Sky, beautiful and full of rare flowers, where live the bird Tjak, whose face is like a human face, the serpent Taksaka, who has legs and wings, and the awan snakes, the falling stars. Still higher in the sky gringsing wayang, the ‘flaming heaven of the ancestors.’ And over all the skies live the great gods who keep watch over the heavenly nymphs.”2 Thus we have it that the island rests on the turtle, which floats on the ocean.

As the last Asiatic outpost to the east, Bali is interesting to the naturalist as an illustration of the theory of evolution. In 1869 Alfred Russell Wallace discovered that the fauna and flora typical of Asia end in Bali, while the earlier, more primitive biological forms found in Australia begin to appear in the neighbouring island of Lombok, just east of Bali. Here the last tigers, cows (banieng), monkeys, woodpeckers, pythons, etc., of Asia are not to be found farther east, and the cockatoos, parrots, and giant lizards predominate. Bali has the luxuriant vegetation of tropical Asia, while Lombok is arid and thorny, like Australia. Wallace drew a line across the narrow straits between Bali and Lombok, the deepest waters in the archipelago, to divide Asia from Oceania.3 Today, however, scientists are more inclined to regard the islands as a transitional region.

As in all countries near the Equator, Bali has an eternal summer with even, warm weather, high humidity, and a regular variation of winds, but the unbearable heat of lands similarly situated is greatly relieved by sea breezes that blow constantly over the descending slopes of the four volcanoes that form the island. The seasons are not distinguished as hot and cold, but as wet and dry. It is pleasantly cool and dry during our summer months, when the south-easterly winds blow, but in November the northwest monsoon ushers in six months of a rainy season so violent that it makes everything rot away, growing green whiskers of mould on shoes that are not shined every day. Then the atmosphere becomes hot and sticky and the torrential rains that lash the island cause landslides that often carry enormous trees into the deep ravines cut into the soft volcanic ash by the rivers, themselves red with earth washed from the mountain. Brooks and rivers swell into huge torrents (bandjir) that rise unexpectedly with a deafening roar, in front of one’s eyes, carrying away earth, plants, and occasional drowned pigs, destroying bridges and irrigation works. It is not unusual for a careless bather to be surprised by a sudden bandjir and to be carried away in the muddy stream.

It is only natural that in a land of steep mountains, with such abundant rains, crossed in all directions by streams and great rivers, on a soil impregnated with volcanic ash, the earth should attain great richness and fertility. The burning tropical sun shining on the saturated earth produces a steaming, electric, hot-house atmosphere that gives birth to the dripping jungles that cover the slopes of the volcanoes with prehistoric tree-ferns, pandanus, and palms, strangled in a mesh of creepers of all sorts, their trunks smothered with orchids and alive with leeches, fantastic butterflies, birds, and screeching wild monkeys. This exuberance extends to the cultivated parts of the island, where the ricefields that cover this over-populated land produce every year, and without great effort, two crops of the finest rice in the Indies.

Despite the enormous population, the lack of running water has kept the western part of the island uninhabited and wild. The few remaining tigers, and the deer, wild hog, crocodiles, great lizards, jungle cocks, etc., are the sole dwellers in this arid hilly country covered with a dusty, low brush. Curiously enough, the Balinese regard this deserted land (Pulaki) as their place of origin. They explain in an old legend that a great city, which still exists, once flourished there, but has been made invisible to human eyes by Wahu Rahu, the greatest Brahmana from Java, who was forced to flee from the capital, Gelgel, to save his beautiful daughter from ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- Introduction

- PART I

- PART II

- PART III

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index