eBook - ePub

Entrepreneurial Ethics and Trust

Cultural Foundations and Networks in the Nigerian Plastic Industry

- 275 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Entrepreneurial Ethics and Trust

Cultural Foundations and Networks in the Nigerian Plastic Industry

About this book

Published in 1999. This book provides an analytical framework of the way culture influences entrepreneurial ethics and trust in a semi-industrial society. Culture provides rules and norms that govern societal behaviour. Yet it differs greatly in the way it influences economic performance across societies.

The book, which embodies both general and micro-institutional perspective on economic behaviour, addresses the core question, how does culture influence entrepreneurial ethics and trust in a developing society?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Entrepreneurial Ethics and Trust by Yakubu Zakaria in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Entrepreneurship. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Method of Analysis, and Theoretical Orientation

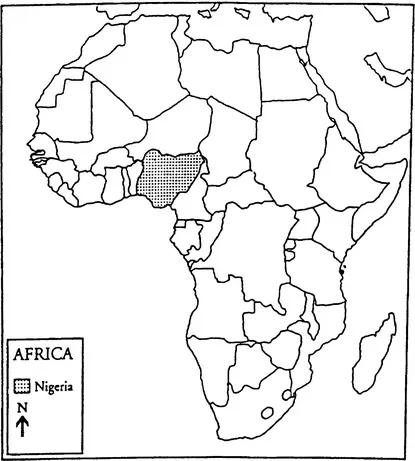

Map 1.1. Nigeria in Africa

Source: Survey Department Kano.

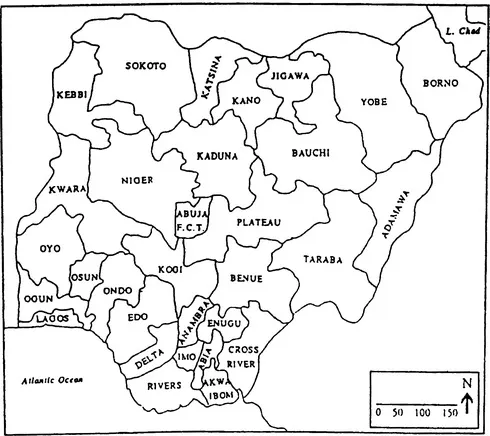

Map 1.2. Nigeria: State Boundaries, 1993–1996

Source: Survey Department Kano.

1 Introduction

Cultural analysis is intrinsically incomplete. And, worse than that, the more deeply it goes the less complete it is. It is a strange science whose most telling assertions are its most strenuously based, in which to get somewhere with the matter at hand is to intensify the suspicion, both your own and that of others, that you are not quite getting it right (Geertz, 1993, p. 29).

Culture is relevant. It is relevant not just because it is a repository of societal values, habits and conventions. It also provides rules and beliefs for what individuals and groups do. Societal values, rules, and belief systems pave the way for rationality, which provides guidance on how individuals and groups pursue economic development. Culture’s significance lies in the sense that it regulates the rate at which societies and groups adapt to change. Despite the ‘aura of illrepute’, ‘multiple referents’, and ‘vagueness’1 surrounding cultural explanations, they are useful in providing us with the subtle meanings that underlie ethics and interpretations about what is rational or irrational economic behaviour across societies. Yet, culture does not operate in a vacuum. Of course, it influences political, economic, and social institutions in society and vice versa.

The study features three firms with distinct cultures and subcultures. Central to the outline of empirical analysis is the cultural dimension of economic performance in the northern Nigerian plastic industry. Of particular significance to the study is the proposition that cultures vary in the way they influence economic performance across societies. Much of the analysis in this book centres on how cultural and religious2 values influence entrepreneurial ethics and trust relations in business transaction. The central focus and important question in this triad study is: how does culture influence entrepreneurial ethics and trust in a developing society?

There is no single but a variety of cultural responses to modernity across societies. As such, when capitalism penetrates developing societies, indigenous cultural values usually determine the social formations of production. Capitalism often assumes a syncretic form peculiar to the cultural environment.3 Culture is therefore not arcane but germane to the study of societal development process.

Equally relevant to this study is the social transformation involved in the adoption of new patterns of manufacturing activities in northern Nigeria where there is much of a heritage in commerce to build on. Today, manufacture involves the introduction of new technologies and social patterns. From a sociological point of view, the most significant aspect of this process is the interplay among these new economic activities and the indigenous patterns of culture and religion.

Culture, a key concept in this study, is an umbrella-term that refers to the all-encompassing material and non-material shared aspect of the human heritage, which includes values, norms, customs, and belief systems that are governed by rules. Culture has three dimensions: the cognitive, normative, and conative. These dimensions, which correspond to thinking, judging, and acting, are regulated by established rules within a particular group. Thus, culture is applied in a pluralistic sense to recognise the existence of subcultural groups within the northern Nigerian society and the business organisations under study. Cultural and subcultural groups often have values, norms and myths that may be similar or distinct from each other.

Values, on the other hand, are ‘relatively general and durable internal criteria for evaluation’ (Hechter, 1993, p. 3). Although they differ in scope and application, they largely influence people’s subjective definitions of what constitutes rationality and which outcomes are labelled as good or bad. Instrumental4 values exercise profound influence on trust, risk, and investment attitudes. Human action depends on internalised values that are acquired or learned through a process of socialisation. Social action and verbal statements provide cues to personal values (Kunkel, 1971). On a general level, societal values and norms tend to exert influence on the individual. This, however, does not foreclose personal or individual values, which sometimes do clash with the values of the larger society. Since values are interwoven with past and present experiences, previous disappointments with old values make people receptive to new ones. Unlike values, norms are evaluative, durable, and external to actors. Norms require sanctions for their efficacy (Hechter, 1993, pp. 2-28).

Islamic and Hausa cultural values are regarded as influences quintessential to understanding entrepreneurial ethics in northern Nigeria. In order to describe these tendencies, entrepreneurial ethics are characterised as both a ‘set of normative prescriptions’, ‘emotions’ and ‘dispositions’,5 which underlie business behaviour. Business, in this context, refers to the sum of organised or patterned activities by which people engage in commerce and industry to provide goods and services and for the acquisition of income.

Business is conceptualised in a much broader context than in its daily Hausa usage. In Hausa society, business activity has several linguistic equivalents. These include koli, which implies the peddling of small wares; bojuwa, or long distance commercial activity; ciniki and kasuwanci, which translate as acts of trade; and sana’a, or occupation. This implies that itinerant vendors and food hawkers with very little capital are regarded as businesspeople. They are considered the same as those engaged in large commercial and manufacturing activities with substantial capital at their disposal. In attempting to overcome these ambiguities, the business activity on which the study is focused is the plastic manufacturing industry in northern Nigeria. In order to grasp the nettle firmly, entrepreneurial strategies in the modern manufacturing activities are examined from cultural and historical perspectives.

Distinct Characteristics of the Study

The distinct characteristics of the study are as follows: First, it investigates the role of Hausa and Islamic cultural values in shaping specific entrepreneurial ethics in northern Nigeria. Essentially, the study provides a cross-cultural comparison of Hausa, Lebanese, and Chinese plastic firms in the northern Nigerian city of Kano. Such a comparative analysis on how local cultural values penetrate modern business organisations is rare. For many years, Nigerian social scientists have underestimated the role of culture in economic development. Although both indigenous and foreign scholars have studied local businesses, few have investigated the cultural impact on entrepreneurial ethics and trust patterns. The plethora of macro-studies, which often do not reveal micro-empirical links, are based on tacit assumptions that economic and political factors operate independently of societal values. This study attempts to bridge the lacuna in the Nigerian business literature.

In spite of the significant cultural and economic differences between especially the Hausa and Chinese, such a comparison makes sense because both groups represent cultures with a strong sense of family. My field studies of 1994/95 and a subsequent follow-up in 1998, shows that most Hausa, Chinese, and Lebanese economic activities are labour-intensive family businesses whose operations are sometimes shrouded in secrecy. In particular, entrepreneurial investment patterns are influenced by a form of rationality that suggests low degree of trust in the business environment. Trust is crucial in influencing investment strategies in Nigeria as in many developing countries. The book explores contributions of private entrepreneurs in the socioeconomic transformation of northern Nigeria, and challenges Weber’s viewpoint that economic progress is less likely in an Islamic society.

A fourth distinct feature of this study is the focus on entrepreneurial performance in the modern manufacturing sector6 from a cultural perspective. The evidence in Southeast Asia suggests that there is no single path to economic development. This shows that genuine development processes need to be approached from cultural vantage points. Thus, sustainable development must consider peculiar local circumstances. Cultural studies are significant in the sense that they allow us to capture the indigenous point of view on how economic goals could be pursued under a given situation. In a semi-industrial city like Kano, business operators and factory workers live in two worlds. In one world, they imbibe the cultural and religious values of the general society; in the other, they are engaged in opposing forms of modern economic activity involving foreign technology and capitalist modes of production.7 An examination of how these dual roles are encountered and reconciled in the economic process is significant. It may suffice to mention therefore, that this comparative study of indigenous and expatriate firms, via cultural processes, is justifiable.

Following logically from these queries and possible conjectures, this study has three main objectives. Firstly, to do a cross-cultural examination of entrepreneurial and managerial strategies. Secondly, to explore entrepreneurial trust and risk-related attitudes that exert significant influence on the nature and size of business enterprises. Here, the patterns and structure of business and their possible effects on entrepreneurial resource controls in indigenous and expatriate firms are relevant. Finally, the study seeks to provide an understanding of the nature and impact of cultural values on the three plastic firms.

Method, and Unit of Analysis

The research reported here makes use of a variety of methods which include: interviews, observations, analysed records from three firms, and reanalysis of secondary materials particularly concerning labour market and entrepreneurial activity from historical perspectives. The units of analyses are three business firms in the plastic sector of Kano, which include an indigenous Hausa, a Lebanese, and a Chinese firm. In addition, some major activities in the commercial sector and their relevance on the modern industrial sector of Kano are examined. The selection procedure of firms was based on accessibility.

There are currently over 60 plastic firms operating within the Kano metropolis. Three firms in the plastic sector, with a total population of 820 employees from which a random sample (N=l 80), was drawn, form the basis of the interview population. Respondents in the study consist of 14 managers and 166 employees in the three plastic manufacturing firms. In addition, 30 interviews were conducted among artisans, and traders outside the three firms. Together, 210 respondents were interviewed.

These respondents, with the proprietors of the plastic firms, are labelled as entrepreneurs in the entire study. Although entrepreneurs are treated as distinct from managers, entrepreneurial, and managerial responses are often lumped together in this study to distinguish them from lower-rank factory employees. Additional information was also received from important figures in the Kano State Ministries of Industry and Commerce. Although the sampling frame may not be strictly representative of a specified population, Zetterberg’s (1965, pp. 128-130) study shows that representativeness is not the only goal in sampling, variation or scope is another. The use of three case studies with considerable variations in cultural and economic potentials is therefore considered adequate. Case studies are useful in providing an understanding of areas of enterprise or organisational function that is often not well documented or amenable to investigation by other methods.8

Entrepreneurial performance regarding modern manufacturing activities is examined, with particular interest paid to the peculiar character of each firm. The approach in this study is comparative and intra-organisational in scope. Essentially, three case studies are compared. The study is largely a fusion of quantitative and qualitative methods. Multiple methods were adopted to tap and maximise the strength of each method. This allows the reduction and prevention of total error through cross-checking and comparing the findings elicited by each method. Web et al (1966) stress the relevance of combining more than one method in research investigation for providing reliable results.

The focused interview method was considered as the most appropriate investigation tool for this study. The interviews focused on variables considered important in analysing entrepreneurial behaviour. In addition, single and group interviews were conducted with key businesspeople and workers in each firm. This approach changed when I interviewed factory workers on the shop floor. Because of their large numbers, group interviews were conducted in which up to a maximum number of ten workers were sometimes randomly selected and interviewed together. Duration of the interviews varied from one hour to one and one-half hours, depending on the setting.

The focused interview method has the ability to reveal ‘deep-seated trends or values’ of the persons being interviewed. Merton, et al (1956), first popularised the method. Its distinct characteristics are as follows. First, the persons interviewed are known to have been involved in some specific kind of activity. Second, a ‘content’ or ‘situation’ is made of the activities in which the persons are engaged. Third, the ‘situational’ or ‘content’ examination provides an interview guide for other related areas of enquiry. Finally, interviews focus on ‘the subjective definitions of persons exposed to the preanalysed situation’. Attention is therefore given to the retrospective and introspective experiences of the interviewed persons. The special application of the focused interview was derived from the economic activities of the entrepreneurs in the plasticmanufacturing sector. Identification of entrepreneurs and businessmen was derived from type of economic activity, tangible and physical assets such as buildings, machines, or the workers they employed. Interview questions focused on the subjective definitions of entrepreneurs on risk, profit, business success and the economic situations or challenges they faced.

In designing the interview questions, the ‘funnel technique’ was applied. In this technique, interview questions normally begin from the general and move towards the specifics. Its importance lies in the clarification of general questions. Since most of the questions were open-ended, a great amount of care was needed to prevent the provision of ‘single links’ or responses by adopting a technique of ‘asking why’ (Lazarsfeld, 1935).9 In-depth interviews were conducted with entrepreneurs, managers, and workers who played essential roles in the firms. All the recorded interviews were later transcribed verbatim on paper, coded, and processed through the statistical method.

Some advantages of the interview method are that literacy is not necessary, especially if the interviewer understands and speaks the local language. This personal approach allows for intimate knowledge and behaviour of respondents (Peil, 1982). An additional advantage of the focused interview is its ability to yield both anticipated and unanticipated results within a short period. It allows for a range of both intensive and extensive interview questions. Furthermore, it enables the interviewer to pick up important cues, from which additional questions and information can be obtained. Some disadvantages of the method, however, are the tendency to put the interviewer in the position of ‘arresting comments’ or ‘cutting leads open before they are fully developed’. There is also a tendency to fixity and the imposition of a fallacy of preconceived topics which respondents may not be familiar with or even exposed to (ibid.).

Participant observation10 in this study is a combination of obtrusive and unobtrusive methods. A major advantage of this approach is the tapping of additional information which respondents could not provide in the interview process. Three informants were hired in the factories for acquiring additional information which the management and owners of the firms may not have provided. The entire period of the field study was six months. During the fieldwork, I observed and compared specific nonverbal behaviour with verbal utterances of both entrepreneurs and employees...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Maps

- Abbreviations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Part I: Method of Analysis, and Theoretical Orientation

- Part II: The Nigerian Plastic Industry, Entrepreneurial Profit Motive, and Resource Controls

- Part III: General Summary, and Conclusions

- Notes

- Glossary of Hausa and Arabic Terms

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index