- 207 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Medieval Bishops' Houses in England and Wales

About this book

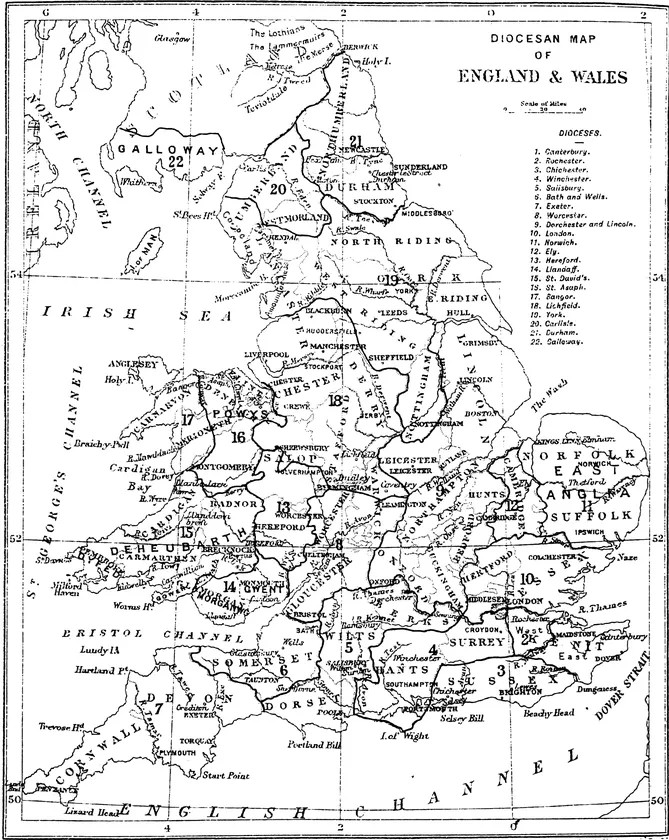

First published in 1998, this book describes the surviving medieval remains there and the far more numerous manor houses and castles owned by the bishops, as well as their London houses. Apart from royal residences these are far the largest group of medieval domestic buildings of a single type that we have. The author describes how these buildings relate to the way of life of the bishops in relation to their duties and their income and how in particular the dramatic social changes of the later middle ages influenced their form. The work of the great bishop castle-builders of the 12th century is discussed, as are the general history of the medieval house with its early influence from the Continent, the changes in style of hall and chamber (still controversial) and its climax in the great courtyard houses of Cardinal Wolsey, Archbishop of York. The book includes over a hundred plans, sections and photographs of the surviving parts of bishops' residences, with a survey of 1647 of the Archbishop's palace at Canterbury before demolition.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 Introduction

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Castles by the cathedral

- Chapter 3 See palaces

- Chapter 4 London houses

- Chapter 5 Castles on the manors

- Chapter 6 Episcopal security in the later middle ages

- Chapter 7 Manor houses

- Chapter 8 Conclusion

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index