![]()

PART I

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

Emily Carr

Source: credit #42673 Provincial Archives, Victoria, British Columbia

![]()

FEMINISM AND PACIFISM: HISTORICAL AND THEORETICAL CONNECTIONS

Berenice A. Carroll

In an essay entitled “Peace Studies and the Feminist Challenge,” Beverly Woodward wrote:

Peace studies is a discipline rooted in our passions—in fear, in revulsion, in love, in hope, in stubbornness: in the fear of what humankind may yet do to itself, in revulsion at the cruel destruction that has already been wrought, in the love of life and the potentialities it bears, in the hope that we may still affect our common human future, in the stubborn refusal to give up in the face of the seemingly insuperable obstacles to the creation of a peaceful and just world order.1

As I read this it struck me that Woodward could as readily have begun with the words “feminist studies” instead of “peace studies.” The statement then takes on some subtle changes of meaning, but still rings true.

This strikingly easy translation from “peace studies” to “feminist studies” (or vice-versa) in such a passage corresponds to an intuitive feeling—a “gut feeling” of mine, which I know at least some others share—that there is some fundamental bond between feminism and pacifism, some inherent and inevitable logic that binds them ultimately together.

Yet there are many facts and arguments that dispute this intuition. Despite the frequent stereotypical association of women with pacifism, women do not find it easy to work for peace. In the peace movement, we often find ourselves outsiders: if not excluded, then accepted mainly as exception or as servant. In the world of national and international “politics,” we find doors closed in our faces, deaf ears turned to our pleas and demands alike. And if we turn to the history of feminist politics, we find sister pitted against sister, suffragette against pacifist, moderate against militant, conservative against radical. The goals of feminism and pacifism may appear to some of us to be in excellent harmony, yet the women struggling for these goals find themselves continually in conflict, not only with the declared enemies of both feminism and pacifism, but with our supposed friends and even with each other.2

Efforts to integrate feminism with pacifism have come mainly from the pacifist side, or rather, from the side of pacifist women. Women in the peace movement have sought to combine their own concerns, to respond to male dominance in the peace movement, and at the same time to promote peace as a feminist issue. Feminists, though widely supportive of peace and internationalism, have been more reluctant to identify themselves with pacifism.

I

One line of argument against linking feminism with pacifism comes from those who see feminism as primarily concerned with opening opportunities for women on an equal basis with men in all aspects of our present-day society, including those relating to war.3 This position is allied with another which holds that women’s subordination and dependency are perpetuated by stereotyped associations between women and pacifism.

This is the view represented, for example, by Emily Stoper and Roberta Ann Johnson in their paper, “The Weaker Sex and the Better Half: The Idea of Women’s Moral Superiority in the American Feminist Movement.”4 Stoper and Johnson argue that feminists have often asserted women’s moral superiority over men, and in particular have claimed a special role for women as peacemakers. Unfortunately this may be turned against us:

Once women admitted that there was a significant difference between the sexes, the argument could be reversed once more and used against them again. Women’s uncorrupted nature, it could be argued, might make her too soft in hard negotiations and too naive in policy-making. … [The claim of moral superiority] has made [women] vulnerable to the charge that being different makes them inferior; has reinforced their traditional roles; and has saddled them with a self-defeating approach to politics. In these ways, it has severely limited women’s access to and effectiveness in the political arena.

Others have argued that for women to refuse participation in military policy and armed forces of nation-states leaves these key arenas of power and control in exclusively male hands and constitutes a failure of responsibility. “By accepting a categorical prohibition against women’s exercise of society’s force, all women become protectees and all men potential protectors,” writes Judith Stiehm. But the “protection” is of a very dubious character. “Not having direct access to force makes women appear as potential victims, while men who are accustomed to acting with force become potential attackers … ” We must then wonder “when protection becomes a racket—when ‘protectors’ align themselves to their mutual advantage while offering false protection to persons forbidden to participate in their own defence.” And Stiehm suggests: “While one does not want to fall into the trap of demanding something simply because it is denied, shared risk and responsibility would seem to be the sine qua non of citizenship.”5

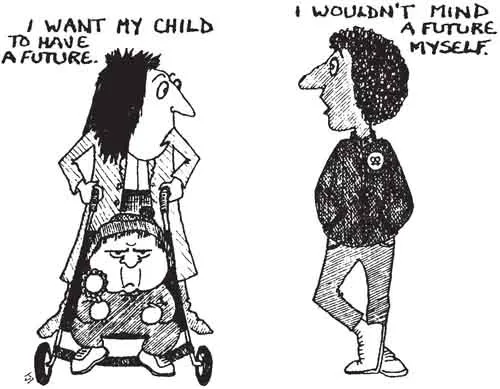

Elizabeth Janeway, in The Powers of the Weak, while not rejecting nonviolence, also cautions that it “may suit women too well.”6 Avoidance of the use of force is so “typically feminine,” she suggests, that it may fail to have the impact of nonviolent tactics carried out by men. Even radical feminists committed to nonviolence may be uneasy on this point. The Feminism and Nonviolence Study Group, concerned that “traditional nonviolence” has been male-led and male-defined, acknowledge too that “certain women’s actions for peace can tend to perpetuate our subordination by portraying women as natural peacemakers and not as powerful activists for change.”7

Source: Breaching the peace (London: Only women Press, 1983)

The Onlywomen Collective, in Breaching the Peace, have argued strongly against the women’s peace movement on the grounds that it is an arena of cooptation and diversion of energies from feminism, that it rests on dangerous “biological” assumptions, that it presents a “reactionary reinforcement of the stereotyping of women,” obstructs us in “taking our own oppression seriously” (by emphasizing the goal of “saving the children” and working for a “greater cause”), and uses arguments very similar to those of “Women for Defence” (protecting the children, keeping the peace, etc.). “We see the women’s peace movement as a symptom of the loss of feminist principles and processes—radical analysis,__Acriticism and consciousness raising.”8

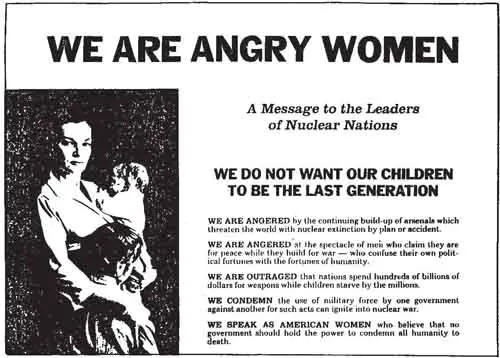

The charge that the women’s peace movement has been sexist may seem strange, but the evidence of it surrounds us still today in many quarters. An example is the striking advertisement circulated by Women Strike for Peace and published in the New York Times on June 1, 1980, declaring “We Are Angry Women.”

Source: The New York Times, Sunday, June 1, 1980

The textual reference to “angry women” calls to mind images of feminism, but what is the picture actually used in the ad? Not women in a protest march or some other militant collective action, but a single, stern-looking woman, attractive and fairly young, with a baby held over one breast and another child leaning against the other, under her protective arm, her hand spread tensely over the child’s shoulder. The subliminal images silently projected are: woman as mother, woman as an isolated being, surrounded only by children, woman as stern moralist, woman as sex object (pencilled eyebrows, emphasis on breasts), woman as anxious and fearful, woman as nurturant and protective.

One of the most recently established organizations in the women’s peace movement, Peace Links, founded by Betty Bumpers, also emphasizes women’s mothering role. The New York Times wrote on May 26, 1982: “‘The disarmament campaign is directed toward women,’ Mrs. Bumpers said, ‘because it is the ultimate parenting issue.’” And the Peace Links brochure says: “We hope that the women of the Soviet Union, just as all women of the world, share our concern for the future of our children.”9 Peace Links and Women Strike for Peace might argue that they are seeking to appeal to a mass audience, and must use images acceptable to that audience. Whether this is a valid position is debatable, but for our purposes the point is that the priority is clear: one wants to get across a message concerning the danger of the nuclear arms race (the “greater cause”); if one can do this by projecting a stereotyped image of woman, one does it, regardless of the possible effects of perpetuating the stereotype.

II

The tension between the women’s peace movement and the organized feminist movement is not new. Historically, relations between the two have been complex and ambivalent.

To begin with, it is necessary to distinguish between women’s organizations and feminist organizations, and even between ...