![]()

1

Interviewing and Deception

DAVID CANTER AND LAURENCE ALISON

Investigative or police decision making involves the identification of and choice between options from amongst a number of different possible lines of enquiry. We argue that this iterative process or feedback loop, the ‘Investigative Cycle’, involves three continuous processes: information collection, investigative inferences and the implementation of investigative actions. Within this cycle we identify a sequence of four stages of potential distortion in information processing: the collection, examination, evaluation and utilisation stages. These distortions include cognitive, presentational, social and pragmatic components. We argue that errors at any of these stages will profoundly effect the other two processes in the investigative cycle. The identification of these cycles, stages and types of distortion allow for the development of a more systematic approach to uncovering where potential weaknesses in an enquiry may evolve.

David Canter is Director of the Centre for Investigative Psychology at the University of Liverpool. He has published widely in Environmental and Investigative Psychology as well as many areas of Applied Social Psychology. His most recent books since his award winning “Criminal Shadows” have been “Psychology in Action” and with Laurence Alison “Criminal Detection and the Psychology of Crime”.

Laurence Alison is currently employed as a lecturer at the Centre for Investigative Psychology at the University of Liverpool. Dr Alison is developing models to explain the processes of manipulation, influence and deception that are features of criminal investigations. His research interests focus upon developing rhetorical perspectives in relation to the investigative process and has presented many lectures both nationally and internationally to a range of academics and police officers on the problems associated with offender profiling. He is currently working on false allegations of sexual assault and false memory. He is affiliated with The Psychologists at Law Group - a forensic service specialising in providing advice to the courts, legal professions, police service, charities and public bodies.

The Investigative Process

Investigative Psychology draws upon a range of psychological principles to contribute to the conduct of criminal or civil investigations and uses behavioural science to assist the management, investigation and ensuing legal outcomes of criminal cases. The discipline has grown out of offender profiling in an attempt to introduce scientific rigour into what were essentially experience based procedures (Canter, 1995).

What fuels the investigative process is the information upon which sequences of decisions are made. A basic example would be matching fingerprints found at a crime scene with known suspects. From this straightforward use of the information drawn from the fingerprint a likely culprit can be identified prompting further actions such as arrest and questioning.

However, in many cases the investigative process is not so simple -detectives often have information that is rather more opaque. For example, they may suspect that the style of the burglary is typical of a number of people arrested in the past. Or they may infer from the disorder at a murder case that the offender was a burglar disturbed in the act. These inferences will either result in a decision to seek further information or to select from a possible range of actions including the arrest and charging of a potential suspect.

Investigative decision making therefore involves the identification and selection of options - options such as suspect selection or selection between specific lines of enquiry. The investigative team hope that such a selection process will lead to narrowing down search parameters. In order to generate and select from a range of options detectives and other investigators must draw upon an understanding of the actions of the offender(s) involved. In other words they must have some idea of typical ways in which offenders behave that will then enable them to make sense of the information obtained. Throughout this process a parallel concern is amassing the appropriate evidence to identify the perpetrator and prove their case in court.

Investigative psychology has systematically identified three psychological processes that may be of particular relevance to the process - assessing the accounts of the crime, making decisions upon this information and developing an understanding of the actual actions of the offenders themselves (Canter and Alison, 1997)

First, the collection and evaluation of information derived from accounts of the crime. Accounts may include photographs or other recordings derived from the crime scene; they may be records or other transactions such as bills paid or telephones calls made or they may be accounts from witnesses, informants or suspects. In the latter case the accounts are drawn from interviews or written reports. Moreover, once suspects are available there is often other information available about them - either directly from interviews, or indirectly through the accounts of others. In addition there may be information provided by experts (i.e. psychiatrists, psychologists) that has to be assessed and may influence subsequent investigative actions. The foundations of any police investigation therefore rest very squarely upon the shoulders of efficient and professional assessment and utilisation of a great variety and quantity of information.

Fictional and media accounts of the work done by detectives tend to exaggerate the second investigative psychology domain - i.e. decision making - as the dominant activity. However this usually takes up far less time than the collection and assessment stages. Though there is remarkably little study of exactly what decisions are made during an investigation, or how those decisions are made, decisions taken on the basis of the information available require some inferences to be made about the import of that information. Much of this import derives from views about, or an understanding of, criminal behaviour. For appropriate conclusions to be drawn from the accounts available of the crime is necessary to have, at the very least an implicit model of how various offenders act. An understanding of criminal behaviour is therefore the third domain.

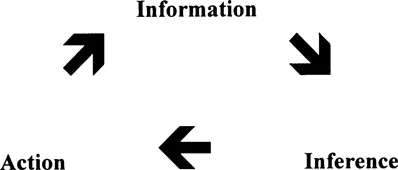

A simple model of these three sets of tasks that gives rise to the field of Investigative Psychology is shown here. (Figure 1.1)

Figure 1.1 Investigation Cycle Giving Rise to Field of Investigative Psychology

- Information - The collection phase: Interviewing suspects, witnesses, the collection of evidence

- Inference - Inferential assessment based upon the information, previous cases etc.

- Action - Investigative decisions taken based upon inferences

The present volume deals with the first area of Investigative Psychology, the examination of the accounts that are given in relation of offences which provide the information on which all aspects of the work of law enforcement agents, and the subsequent work of the courts are based. These accounts have to be collected, assessed and evaluated as effectively as possible if an investigation is to proceed with any chance of success. In the following chapters various aspects of the process of information retrieval and assessment are examined.

The Process of Information Retrieval and Its Assessment

The decision model of investigations demonstrates how crucial is the information that is collected a part of any criminal or civil enquiry. At many stages in the investigative cycle material of many kinds becomes available. It all has to be assessed for the information it offers. If the information derived from these accounts is to contribute to the investigation it must be systematically recorded and evaluated.

The process of recording and evaluation of information of relevance to criminal investigations and the legal process goes through a number of stages. At each of these stages there is the need for quality control - both in the way that the material is obtained and recorded and in the way that it is assessed. If professional standards are maintained throughout - from the collection stage, through to utilisation of the material, then there is increasing likelihood that any decisions based on the information will be valid and worthwhile. Yet there are many possibilities for distortion and the introduction of bias into this process, especially when relying on the verbal accounts given by the main participants in the crime, witnesses, victims and suspects.

The police investigator therefore has to carry out a task that has some parallels to a chemist trying to purify a compound in order to test its properties. There are many stages of filtration and titration that will remove impurities and at each of these stages there is the risk of introducing further impurities. But the analogy to a chemical process has to be treated with caution. The very impurities that need to be removed may themselves indicate important aspects of the crime, as when a suspect claims they have an alibi that is not substantiated. For even though this does not prove guilt it increases suspicion. Further there may be no definitive account of the offence ever available because everyone involved is trying to make sense of complex circumstances in which they were participants. Issues like motivation and consent, so crucial for the judicial process, for example, may always be matters of interpretation rather than clearly objective fact.

Success in collecting, assessing and evaluating the information needed for an investigation therefore requires a clear understanding of the theory behind the process, of the most appropriate means of collecting the materials and of the constraints and limits on those means. The investigator must secure strong evidence and ensure that the irrelevant, distorting information is removed. Reaching the ‘best solution’ (i.e. as close to the facts of the offence as possible), relies on a form of professionalism that requires a detailed understanding of the potential strengths and weaknesses of all aspects of collecting the information. Understanding of the most appropriate ways in which to assess and evaluate that information is also necessary.

The Processing of Investigative Information

In many areas of research involving responses from people the integrity of the initial information is taken for granted. Few opinion pollsters assume that the answers offered on the High Street are deliberately distorted. Historians examining early documents may expect the authors of those documents to be biased but will rarely consider how the trauma, for example, that the author might have faced during the events they describe, may have distorted his or her attention at the time. Psychologists do not seek, nor are they offered accounts of what goes on in their laboratories from the perspectives of different participants, deriving some consensus of the views offered on which to base the tests of their hypotheses. Yet all these approaches and issues form the day to day mix on which criminal investigations are based. As a consequence, it is of value to examine the various stages that information goes through, on a par with the purification of the chemist, in order to understand more fully the different aspects of information retrieval and assessment that are so crucial for solving crimes.

In essence, accounts of crimes are processed through four stages. A range of distortions may occur at any one (or all) of these stages. Different procedures may be necessary to enhance the detail and reduce distortions at any stage. A cumulative effect of ‘impurities’ introduced early in the process may also be expected. Assuming a crime had occurred, for instance when none had, as would be the case with a false allegation, could lead to many confusions and inappropriate actions.

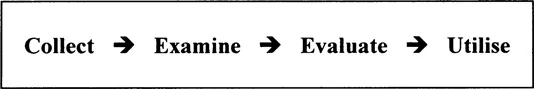

A graphic representation of the sequence of stages is given (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Processing Investigative Information

The following chapters deal in various ways with each of these stages, but it is worth emphasising at present that as the information derived gets further away from the original source there is more influence of inference processes. With some training in collection, observing the crime scene or interviewing witnesses can be a relatively overt, neutral process. The examination of the information requires some consideration of how it was collected as well as some knowledge of the criminal processes to which it refers. Evaluation takes the inferences a stage further by comparing the actions revealed with known patterns and actions of offenders. At the end of the process the possibility for using the inferences as a guide for investigative actions has to be assessed in relation to other aspects of the investigation. Thus material that seems important in the early stage of the detection process may turn out to be of little utility when seen in the light of other information collected later.

This examination of the processing of accounts of crime helps to emphasise the ways in which inferences can become disassociated from the original, possibly hesitantly offered, material. For example the reconstruction of what an assailant may have looked like, or the possibility that a supposed murder victim had intended to commit suicide, or a description of abuse in childhood, may all take on an unchallenged existence by the time they are utilised to guide crucial decisions in an enquiry. Evidence cannot be constantly questioned in the throes of detection. Judgements have to be made about the information collected and the investigation moved on from there. This is all the more reason why each of the stages requires careful examination.

Possibilities of Distortion

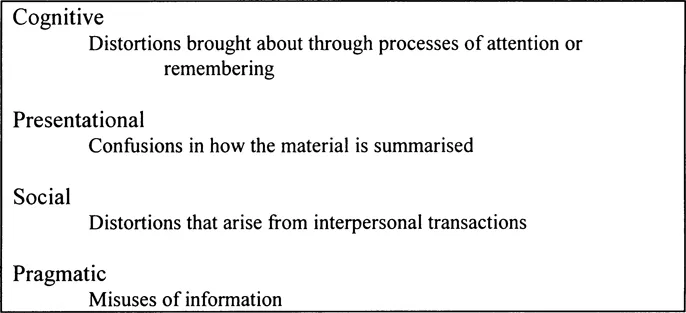

There are many possibilities for distortion of the information at the different stages of an enquiry. Some aspects have been more fully examined by psychologists than others, but four aspects can be identified, which broadly map onto the four stages mentioned above.

Figure 1.3 Possibilities for Distortion of Information in Police Investigations

At any stage a variety of distortions may occur - cognitive, presentational, social and pragmatic. The following chapters provide many examples of these possibilities. For instance a major aspect in the development of interview technique has been to reduce the distortions brought about by cognitive processes. By contrast research on the detection of deception has been more oriented to examining the ways in which the social transactions between people and the way information is presented can lead to biases and confusions. Some consideration of the use of expert testimony also highlights the ways in which material can be inappropriately used by investigators or the courts.

The People of the Drama: Explanatory Roles in the Investigation of Crime

Another aspect of investigative information that helps clarify the possibilities for distortion is the significance of the different relationships the people involved may have to the account they are giving or examining, their ‘role in the drama’. As already emphasised the information can come from many different sources, what is left at the crime scene, or in various records, accounts given by witnesses, victims, informants or suspects, reports from experts and opinions from people involved in or associated with the investigative process. Perhaps the most significant variation this introduces is the form of contact the individual providing the account has to the account they are giving. This relationship brings with it many different contexts for the accounts that are given. Understanding the role and context of an account helps to alert us to the possibilities for distortion.

At each stage of the enquiry individuals (whether members of the enquiry team, witnesses, suspects or barristers) ‘play’ different roles. Each ‘player’ will have varying degrees of involvement with, and skill in conveying or eliciting an account of the offence and each individual will ‘play’ his/her role as a function of the context in which the eve...