![]()

Part 1

Introduction

![]()

Chapter 1

The Setting: a Profile of Leigh Park

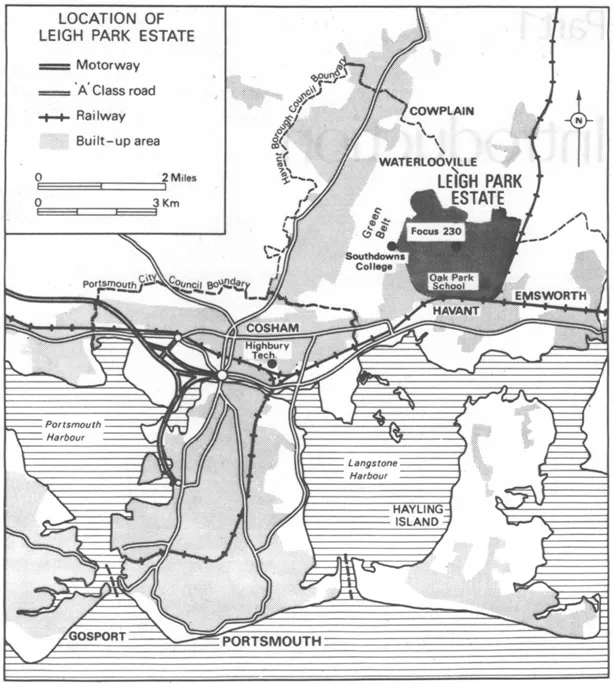

The spread of city populations into the surrounding countryside has become familiar since the early 1920s. Large concentrations of local authority housing built on the peripheries of towns and cities now form a standard pattern throughout much of Britain. Roughly one-third of the nation’s housing stock is local authority-owned and -controlled and a large proportion of it is situated on the ‘city rims’. Some of these estates have been developed beyond the rims of cities. In the jargon of planners, they are referred to as ‘areas of urban overspill’; they pose a number of political, economic and social problems both for their residents and for the policymakers responsible for them.

This book is about the exploration and subsequent action of a research team in one such overspill area. While the focus of our inquiry was the provision of adult education, it was impossible to isolate this from its surrounding social context. We became involved with a wide range of locally organised activities; we often operated in a way that our professional colleagues wanted to label ‘community work’ or ‘social work’; and we were much less involved than we had expected in the rather formal evening classes that are the staple provision of ‘adult education’. Thus in the chapters that follow we describe the detail of our inquiry, which lasted for three and a half years in Leigh Park, both emphasising those factors and events that seem specific to life on the estate and drawing attention to what generalisations can be made from our findings. We return in the final three chapters to the questions that preoccupied us throughout our inquiry: how can education for adults be made more accessible to the majority who currently play no part in the existing adult education services (the ‘non-participators’, as today’s jargon has it)? What changes will be necessary if this is to happen?

Over the past five decades conventional thinking has produced a stereotype housing estate where people accept subsidised accommodation, make little effort to care for council property and have limited desire or need for community facilities.

The evidence provided by tenancy agreements drawn up by many local authorities1 shows until quite recently a clear expectation that council tenants would behave differently from private householders. Implicit in this paternalistic view has been the notion of second-class citizenship, especially to be seen in the numbers of housing estates that have become stigmatised over time, often through isolated ‘anti-social’ behaviour by some of the tenants.

Certainly many local authority housing estates have inadequate community facilities such as shops, meeting places or play areas. Poor public transport and long journeys to work may well produce burdens of expense and loneliness among residents. We would argue, however, that each housing estate possesses its own unique history and development which needs to be carefully taken into account when considering the attitudes of the residents towards their environment and its potential needs. The greyness of conventional stereotypes is largely the product of standardised architectural and planning forms, themselves constrained by centrally established limits to housing expenditure. But the residents are far from grey. Ideas about apparent differences from other sections of British society appear to stem from the attitudes held by outsiders - people living in areas adjacent to estates and also by those professionals and others in the social or educational services whose job is to help meet the needs of residents.

The task of the New Communities Project team was to observe and examine the attitudes of residents and professional educators towards adult education provision as it existed in 1974 and, if necessary, to develop more relevant approaches. The first two chapters of this book are concerned with the social context that formed the arena for the Project’s work and, equally importantly, with a rationale for establishing it. Based on a long tradition of providing adult education services through local education authority centres, Workers’ Educational Association branches and university extramural studies departments, assumptions were made about the need to adopt alternative strategies of provision. Assumptions were also made about the reasons why people living in Leigh Park did not make fuller use of existing services. Later chapters describe events that caused modifications to both sets of assumptions and led us to develop what we call an ‘ecological’ approach to adult education and a parallel ‘non-formal’ programme alongside the more usual formal classes. The starting points for learning must be found within the social context of people’s lives and not artificially imposed in a formal way from outside sources.

The origins of Leigh Park

Over the past two centuries the growth of Havant, Fareham and Gosport has been inextricably linked to developments in Portsmouth. Havant, a town with Roman and Saxon origins, began to grow in importance as businessmen and naval officers from the city of Portsmouth built substantial houses there in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Portsmouth was eleven miles away but reasonably accessible on coach roads. After the opening of the railway to Brighton in 1847 and to London in 1852, Havant became a suburb of the city and was inhabited largely by middle-class families.

The largest of the houses built by these new families was Leigh Park. It was situated in nearly 2,000 acres of land to the north of Havant, enlarged by William Garrett in 1802 and sold in 1819 to Sir George Staunton. Sir George developed the estate and landscaped part of it to form a garden, influenced strongly by his experience and knowledge of Chinese horticulture. In 1875 the Staunton family sold Leigh Park to Sir Frederick FitzWygram. Sir Frederick, who was a veteran of the Crimean War, was active in public affairs locally, being both a magistrate and a Member of Parliament for South Hampshire; he held his seat for twenty-two years until his death in 1902. The estate remained in the hands of the FitzWygram family until the death of Sir Frederick’s daughter in 1943.

During the tenure of the FitzWygram family changes were occurring in the region. In 1894 the Havant area was reorganised into urban and rural districts; Havant and the adjoining village of Warblington became Havant Urban District. Portsmouth too was growing in population as its status as a major naval port increased and the naval dockyards were expanded to cope with the requirements of a sophisticated fleet of warships based on the port. In the 1920s Portsea Island became too small for its population growth and the city boundaries were extended along the coastal strip on the north of the island to include Farlington in 1932. Thus for the first time the boundaries of Portsmouth and Havant met.

It is interesting to reflect on the probable causes of Portsmouth’s expansion during the 1920s and 1930s. Economically the area was becoming less dependent on the naval dockyard. Disarmament had become government policy after 1918, and, although redundancy and a general running down of the dockyard work force occurred, the effects of economic depression were less severe in the area than in many northern industrial towns. Portsmouth had become a popular seaside resort, and to some extent the earlier impetus of population growth could be absorbed by the employment requirements of the holiday and distributive trades, so softening what otherwise may well have been a severe economic depression in the area. Industrial estates that centred on consumer products were encouraged along the coastal strip, and private housing development was accompanied by council housing within the new city boundaries. The older workers’ housing in the Portsea district around Portsmouth dockyard was seen by many residents of the city as a slum area and the tenants of the cramped streets were stigmatised as ‘Portsea-ites’.

The Second World War brought dramatic and tragic changes for many families living in the district. Portsmouth contained a number of military targets, notably the naval repair yards, submarine and torpedo bases and a variety of radio, radar and gunnery installations. Although German bombing raids destroyed buildings in many parts of the city, the greatest damage to private housing occurred in the Portsea districts surrounding the dockyard. By 1945 Portsmouth Council faced a grave problem of rehousing families made homeless from the ravages of war as well as an increased demand for homes from newly married ex-servicemen. The council had a programme of rehabilitating war-damaged property, but its main opportunity for large-scale housing development existed over the city boundary in Havant Urban District.

An astute purchase during 1943 and 1944 of 1671 acres of the Leigh Park estate by the city council from its general rate fund account ensured that land would be available for future development. The land cost Portsmouth City Council a little over £80 per acre.2

Building began in 1948. At this time of acute housing shortage, a number of families were already living on the site in an ex-naval camp consisting of Nissen huts. Piecemeal development caused concern in both Portsmouth City and Hampshire County Councils, but a decision on cost grounds to develop as a satellite area rather than a designated ‘new town’ meant an inevitable shortage of amenities and facilities. The scene was set for the growth of an amorphous sprawl of houses which would be occupied by families alien to the residents of Havant.

The story of Leigh Park’s development is not unique. Sadly, it can be applied to many areas surrounding other large cities in this country. In the early days of the estate three-quarters of the working population had to commute to and from Portsmouth, since at that time there was little alternative employment in the immediate vicinity. A large number of men worked in secure, but low-paid, jobs. Bus fares were expensive and many made the daily eighteen-mile return journey on bicycles.

Most of the new tenants had grown up and had lived in well established neighbourhoods in Portsmouth. Although people welcomed better housing conditions, some found it difficult to settle down in alien surroundings removed from family and friends and the ‘corner shop’ community. There were few amenities. For some years more than 10,000 people lived on Leigh Park before any shops were opened, and this influenced many families to re-establish their former links with the city through weekend marketing. As more houses were built, prospective tenants became uneasy at the prospect of settling permanently on the estate, but saw the move more in terms of a temporary solution to their housing problem – a transit camp before finally settling down elsewhere.

The restlessness of some residents, particularly adolescents, was manifested in damage to property and materials. They quickly became labelled as vandals who were apathetic to any attempts by the local authority to provide help. The earlier stigma that attached to people living around Portsmouth dockyard was transferred to Leigh Park residents, not only by Havant dwellers, but also by people in Portsmouth. In the 1960s, as private estates were developed rapidly in the Havant area, many skilled workers gave up their tenancies on Leigh Park to purchase their own homes nearby.

The growth of Havant Urban District population, although swollen by 33,700 Leigh Park residents (1971 Census), had been due mainly to a large number of owner-occupied and privately built houses. From the 1951 total of 35,146 residents its population had increased to 111,520 in 1972. By contrast, Portsmouth’s population had declined over the same period from 233,545 to 196,950. Thus by the start of the New Communities Project in 1973 Leigh Park was almost fully developed, with a town-sized population surrounded by a number of large private housing estates, but geographically separated from them by a railway line and a green belt of government-owned land all within the Havant boundary.

However, in spite of its town-sized population and its location within the boundaries of one borough, the administrative structure of local government is complex for a Leigh Park tenant. He pays rent to Portsmouth Corporation and rates to Havant Borough. But he receives education and social services from Hampshire County (since 1974 the overall authority for the area) and technical and leisure services from Havant Borough.

As the estate developed, and because it came to contain 40 per cent of Portsmouth’s council housing stock, decisions taken by Portsmouth Housing Committee frequently affected Leigh Park tenants, who in turn had no means of influencing the committee members through normal political channels. The Portsmouth Housing Committee continues to exercise its right as a landlord to control the granting of tenancies to applicants on its own housing list as vacancies occur on the estate; a young family acquiring a council house is more than four times as likely to be rehoused in Leigh Park as in the city area.3

In the next generation, what was a Portsmouth housing problem now becomes the responsibility of Havant Borough. The Borough Treasurer has outlined the size of the problem of housing second-generation Leigh Park tenants:4

The Portsmouth problem: the problem reiterated: Portsmouth house a family in Havant (man, wife and two young children). Twenty years later the children require their own homes. The parents’ house, when eventually vacated is filled by another immigrant family. Assume only one child in two requires housing in the district. Result: for every Portsmouth family housed in Havant, the Borough Council has to provide one new house every twenty years. This is the equivalent of a perpetual 5 per cent demand (with ten thousand houses as a base, Havant would have to find five hundred houses every year to meet the needs of the original progeny). Eventually there will be no land left in the Borough for housing. Building at three hundred units per year would use up all available land in ten years.

The emerging picture of a cuckoo in the nest which arrives without invitation and eventually grows to swallow all the borough’s resources while the progenitor that spawned it enjoys relatively copious resources may seem to overemphasise one aspect of the situation. However, we produced a comparative study which does point to an imbalance of services available as between Havant and Portsmouth – and the results of the study surprised politicians and administrators in both areas. The fact remains that Leigh Park has not been seen favourably by Havant people and appears to have been forgotten by Portsmouth once individual housing needs have been met. The rapid growth in south Hampshire generally has placed innumerable strains on existing facilities and services. Leigh Park, the boundaries of which encompass five of Havant’s political wards, has had to compete, often unsuccessfully, for resources with other fast-growing areas nearby, and local planning has been almost exclusively concerned with housing.

Provision of housing on Leigh Park for specific categories of tenants has produced an imbalance in the numbers of the most vulnerable sections of society, namely children under the age of five years and adults aged over sixty years. Thus the estate has grown in size over a twenty-five-year period but has not enjoyed a natural development in the age structure of its population. It contains a higher proportion of residents who by virtue of their age would be considered potentially ‘at risk’ by social services. The problems of these residents have been exacerbated by an unprecedented increase in Havant Borough’s population as a whole which has stretched existing services fully.

Problems of those residents with low incomes are exacerbated by the fact that the south-east of England has a cost of living second only in England and Wales to that of London. This shows itself in a number of ways, but particularly in the high cost of land and the high level of rents and rates. In 1973 a comparison of Portsmouth’s rents with those of other local authorities revealed that only certain London boroughs – the City, Kensington, Chelsea, Kingston-upon-Thames and Sutton – charged higher rents than Portsmouth Qty Council. In 1971 9,154 households were paying these rents in Leigh Park, and although 14.8 per cent of Portsmouth council tenants received a rent rebate, they were still paying higher rents than a tenant in the average county borough who was not receiving a rebate. The amount of rent arrears, however (twice that for Southampton), was higher than for neighbouring areas, contributing to evictions and to the problems of homelessness.5

A profile of the estate

It is from a general background of the area’s growth and development that we now consider the details of the estate itself. The population is a very young one, with 46 per cent under twenty years old. Forty per cent of families have more than three children compared with less than 5 per cent for the rest of the Borough. In 1974 some 60 per cent of all children in the Borough aged three to five lived on Leig...