- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1986. This book explores developments in the cinema, sport, holidays, gambling, drinking and many more recreational activities, and situates working-class leisure within the determining economic and social context. In particular, the inventiveness of working people 'at play' is highlighted.

Drawing on an extensive range of source material, the book has a wide general appeal, and will be useful to those professionally concerned with leisure, as well as teachers and students of social history, and all those interested in the patterns of working-class life in the past.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Workers at Play by Stephen G. Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Entertainment Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The demand for leisure

During the inter-war years leisure in Britain was provided in three main forms. First, there were commercial providers of recreational products, facilities and services, who regarded leisure as a source of profit. In very broad terms, business enterprises penetrated many leisure activities, including sport, entertainment and the arts, and holidays. Second, recreation was provided in the voluntary sector by a variety of associations and societies. Voluntary recreation and leisure groups banded together in most towns and consisted of youth organizations, outdoor activity groups, sports clubs, cultural organizations and so on. It is correct to say that there were very few leisure pursuits which were not catered for in the voluntary sector. Lastly, there was leisure provision in the public sector, both at national and local level. The central and municipal authorities provided a wide array of recreational amenities such as urban parks, playing fields, swimming baths, concert halls, libraries and museums. As will be claimed in subsequent chapters, there was an expansion of all forms of leisure in the 1920s and 1930s. One of the reasons for this is that the demand for leisure goods and services was buoyant.

This chapter will consider the nature of the demand for leisure; more specifically, the demand for leisure time and the financial means to enjoy that leisure time. The demand for leisure is determined by a number of economic and social variables. For instance, it is clear that real wages, hours of work, the price of recreation, the level of transport systems, and the general commitment of communities and governments to recreational provision will all have an impact on total leisure demand. Here, it is assumed that the demand for leisure is determined by two main factors: first, purchasing power in terms of wages and the cost of living; and second, the amount of spare time available in terms of the number of hours worked and holidays taken. The rationale behind this is that purchasing power provides the consumer with greater command over leisure goods and services, particularly in the commercial sector, while reduced working time simply provides the consumer with more leisure. Having said this, the chapter will examine where appropriate those other factors which directly impinged on demand. Finally, something will be said about the campaign of the trade unions for greater leisure time in the form of the shorter working week and paid holidays. Because of the differences in working-class experience created by the disparities of region, occupation, skill and gender (the average worker is something of a statistical illusion), and also the lack of certain key data, the following analysis is not meant to be conclusive, merely suggestive.

Purchasing power

It is important to examine purchasing power, for without money individuals could not have participated in the commercialized leisure sector. In addition, income was also required in the voluntary sector for membership fees, equipment, club premises and so on. Equally, money was exchanged for municipal services as in the use of swimming pools and park amenities, as well as in the hiring of playing fields and town buildings for organized recreation.

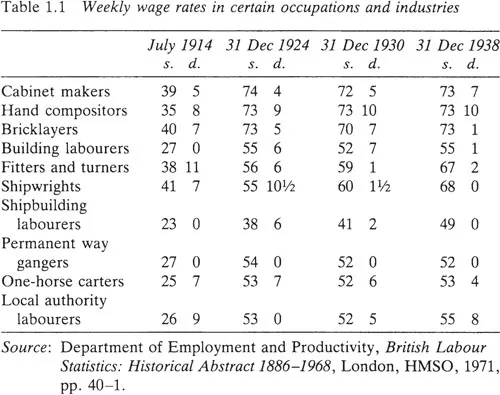

For the account of wages and the cost of living a number of sources have been consulted ranging from the statistical to the impressionistic, though quantitative estimates will be stressed. Various indices have been constructed for the movement of basic weekly rates of wages. Although there are many problems connected with the construction of such an index, the general trend is fairly clear. There was a strong rise in money wages immediately after the end of the first world war. In 1920, however, came a dramatic collapse which lasted until 1923, by which time wages had fallen to approximately twice their 1913 levels. For the rest of the decade they stayed fairly stable, but in 1930 there was a further decline which, though only moderate, lasted until 1934. Thereafter, wages rose slightly, so that by 1938 they were about double the pre-war level.1 Thus, whereas the average weekly wage in 1913 was £1.60, by 1938 it was about £3.50.2 A wage index is, however, only an average, so to be more precise about the true movement in money wages it is necessary to investigate further.

It is quite clear from the statistics that there were wide differences in wage rates, determined by occupation and skill.3 Although these examples follow the overall national trends, they also illustrate the differentials according to industry and grade. It can be seen that not only did wages differ between the skilled and the unskilled, they also differed within these two distinguishable groups. Obviously differences in weekly wage rates had an effect on the workers’ ability to consume leisure; a bricklayer on 65s 6d or a hand compositor on 73s 10d in 1934 was likely to consume more units of leisure in the market place (ceteris paribus) than was a goods porter on 43s or a building labourer on 49s 4d. Hence one study of income and expenditure patterns made in 1936 found that spending on recreation increased with average weekly income: for a family on £2 11s 4d, expenditure on recreation amounted to 1s 3d, whereas for a family on £3 17s 6d, recreation spending was 5s 01/2d.4 The figures for wage differentials are given in Table 1.1. In addition to this, there were also regional variations in wage rates. In London, for example, the weekly wage in 1928 for wiremen was 84s, for carpenters and joiners 77s, and for engineers’ labourers 45s 31/2d, compared to the national averages of 74s 5d, 72s 5d, and 41s 11d respectively.5 If the further complexities of unemployment, short-time working, basis of payment, bonus systems and so on are taken into consideration, the difficulties of using this data would be increased. Nevertheless, enough has been said about the movement in money wages to suggest that those workers in full employment in 1938 were in a better position to purchase leisure than they had been in 1914. The analysis will now continue by considering the cost of living factor.

As with weekly rates of wage, a number of cost of living indices have been compiled.6 The one used here has 1930 as the base year (see Table 1.2). The movement of prices follows a similar path to that of money wages. There was price inflation in the immediate post-war period followed by a rapid deflation in the two years after 1920. For the ten years after 1923 there followed a much more moderate decline in prices, and from the trough of 1933–4 prices increased slowly to the outbreak of the second world war, so that the cost of living index lost 37.4 points between 1919 and 1938.

Using the movement in money wages and the cost of living as a basis for calculations, what can be said about the overall change in the level of real purchasing power? Both money wages and prices fell in the period after 1920, but prices fell at a faster rate than wages, thus bringing an increase in purchasing power or, to put it another way, an increase in real income per head.7 Table 1.2 provides figures showing the movements in money wages, the cost of living and real wages. Moreover, the working population also benefited from a change in the distribution of income in favour of wages, a fall in family size, and a fall in the price of foodstuffs – a major component of the working-class budget.8 Certainly, the conclusion to be drawn from a study of the statistics of money wages, the cost of living and real wages points to an increase in working-class material standards of living, though once again the significant differentials in wage rates should be stressed. How, then, was leisure provision affected by this increase in purchasing power?

Table 1.2 Wage and cost of living indices (1930 = 100)

| Average wage | Cost of living | Average real wages | |

| 1913 | 52.4 | 63.3 | 82.8 |

| 1919 | - | 136.1 | - |

| 1920 | 143.7 | 157.6 | 91.2 |

| 1921 | 134.6 | 143.0 | 94.1 |

| 1922 | 107.9 | 115.8 | 93.2 |

| 1923 | 100.0 | 110.1 | 90.8 |

| 1924 | 101.5 | 110.8 | 91.6 |

| 1925 | 102.2 | 111.4 | 91.7 |

| 1926 | 99.3 | 108.9 | 91.2 |

| 1927 | 101.5 | 106.0 | 95.8 |

| 1928 | 100.1 | 105.1 | 95.2 |

| 1929 | 100.4 | 103.8 | 96.7 |

| 1930 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 1931 | 98.2 | 93.4 | 105.1 |

| 1932 | 96.3 | 91.1 | 105.7 |

| 1933 | 95.3 | 88.6 | 107.6 |

| 1934 | 96.4 | 89.2 | 108.1 |

| 1935 | 98.0 | 90.5 | 108.3 |

| 1936 | 100.2 | ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The demand for leisure

- 2 Commercialization and the growth of the leisure industry

- 3 Leisure provision in the voluntary sector

- 4 State provision: the role of central and municipal authorities

- 5 Work, leisure and unemployment

- 6 The Labour Movement and working-class leisure

- 7 The politics of leisure

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index