- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1998, this volume examines the 'economic miracle' of Taiwan's remarkable transition from poverty to one of the world's most affluent economies, ten years after its emergence from martial law. Gerald A. McBeath explores Taiwan from its time as a country barely recovered from Japanese occupation and wartime damage to a nation filled with new office buildings and skyscrapers where few think twice about frequenting expensive restaurants. Beginning with the State of Taiwan between 1945 and 1986, McBeath progresses through the transformation of the Party-State, the changing status of economic interests, policy-making in the democratic era and Taiwan's internationalisation campaigns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wealth and Freedom by Gerald A. McBeath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

When Chinese Nationalists retreated from the mainland to Taiwan in 1949–50, they governed a people barely recovered from the Japanese occupation and Pacific War. Wartime damage to factories, plants, and buildings had not been completely repaired; housing was scarce for the flood of mainland Chinese immigrants; food was barely sufficient to feed a population that within a year had increased by over 20 percent. Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was about US $110, which placed Taiwan among the poor, or “underdeveloped”, countries emerging from the Second World War.

In 1997, nearly a half-century after it became the headquarters of the Republic of China, Taiwan has entered the select list of wealthy nations. New office buildings and skyscrapers reconfigure the urban landscape, and few buildings date to the 1940s. Most people can own their own homes, and housing is abundant at affordable prices. Few think twice about eating out at expensive restaurants. Per capita GDP is about US $13,000. Taiwan is the world’s fourteenth largest trading nation, has the third largest foreign reserves, and is the sixth largest outbound investor. The International Monetary Fund reviewed Taiwan’s economic indicators in 1997 and placed it for the first time among the world’s “developed” nations. This transition from poverty to affluence in less than 50 years constitutes an “economic miracle”, and its explanation is the first theme of this book.

For its first 40 years on Taiwan, the Nationalist government ruled under martial law. Public demonstrations of any kind were banned, as were strikes, peaceful marches, and rallies. Although free elections were conducted at the local level, no party could form in opposition to the ruling Kuomintang (KMT or Chinese Nationalist Party). Newspapers and electronic media were censored. Vocal opposition to the regime was hazardous, and dissidents routinely were arrested and imprisoned during the KMT’s “White Terror”.

Now, in 1997, Taiwan’s government has been operating without the crutch of martial law for ten years. Demonstrations, rallies, marches and strikes, while not daily events, happen freely and usually peacefully. Since 1986, political parties have organized. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and New Party (NP) together control nearly half of the seats in the Legislative Yuan and can stall and sometimes defeat government proposals. Taiwan has a free press and alternatives to government broadcasting stations. Critics of the regime do not face arrest. This transition from authoritarianism to democracy in little more than a decade constitutes a “political miracle”, and its explanation is the second theme of this book. Wealth and freedom have been goals of statesmen throughout the 20th century, and they have been achieved more nearly in Taiwan than in any other Chinese state system in world history. Their achievement, however, has come at the cost of increases in pollution, in social disorder, and in “black and gold politics” (influence of organized crime and the super-rich in politics) to name three negative externalities of rapid economic development and political liberalization. We will consider these negative correlates along with the positive consequences of Taiwan’s economic and political development, but our main objective is to examine the conjunction of wealth and freedom. Specifically, we seek to understand the impact that economic systems, forces, and changes have had on Taiwan’s political system and, conversely, the impact that changes in the state and democratization have had on economic fortunes. Before turning to the plan of the book, however, we need to introduce Taiwan: its land and environment, people and culture, institutions, and geopolitical status in the late 1990s.

Land and Environment

Taiwan’s geography, climate, and resources distinguish it from all of its East Asian neighbors.

Geography

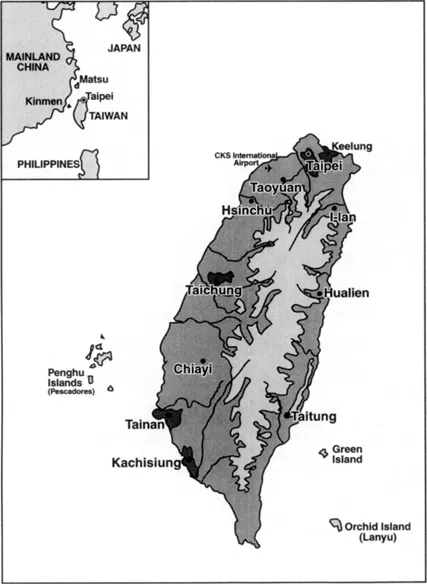

The island of Taiwan is the largest body of land between Japan and the Philippines. It lies on the edge of the Asian continental shelf in the western Pacific. Resembling the shape of a tobacco leaf, Taiwan is located between 21°53’50” and 25°18’20” north latitude and between 120°01’00” and 121°59’15” east longitude. It crosses the Tropic of Cancer in a position comparable to Cuba. The island is about 240 miles long from north to south and 98 miles broad at its widest point. No part of Taiwan is more than 50 miles from the sea. (See Figure 1)

With a total area of 13,884 square miles, Taiwan would be the second smallest province of China (after Hainan island). It is about the size of the American states of Connecticut and New Hampshire, a little larger than the Netherlands, and a bit smaller than Switzerland. Politically, 77 surrounding islands, 13 of them abutting the Chinese mainland and 64 comprising the Penghu group in the Taiwan Strait, form part of Taiwan.

Figure 1. Map of Taiwan

Source: Government Information Office, ROC, 1997.

The strait itself separates Taiwan from the Chinese mainland by 100 miles of turbulent waters. Taiwan lies some 700 miles south of Japan and 200 miles north of Luzon, the northernmost island in the Philippines. Taiwan is equidistant from Hong Kong and Japan and sits astride strategic shipping lanes in East Asia.

Mountains form the central backbone of Taiwan, stretching from northeast to southwest. About 32 percent of the land area is steep mountains of more than 3,280 feet in elevation; hills and terraces between 328 and 3,280 feet above sea level comprise 31 percent of the land area; and alluvial plains under 328 feet in elevation make up the remaining 37 percent.1 Most of Taiwan’s 21.4 million people live on the plains, giving Taiwan a population density of 590 persons per square kilometer, the second highest (after Bangladesh) in the world.

Taiwan has 151 rivers and streams, most of which originate in the central mountain range and flow either east or west. Rivers are short and swift, lending the island a radical drainage pattern as they become torrential during heavy rainstorms and disgorge silt and mud as they descend from the mountains.

The vegetation zones of Taiwan range from tropical to alpine, and natural flora resemble those of the Chinese mainland. Once, the island was heavily forested; today, stands of acacia cover many areas, and bamboo groves grow in central and southern regions. Soils range in fertility because of leaching through centuries of irrigation and heavy rainfal1.2

Climate

Taiwan is hot, steamy, and windy much of the year because of its position relative to the ocean and the Asian mainland, ocean currents, and the pattern of its mountains. Northern Taiwan has subtropical weather, and the south is tropical. During the winter, from October to March, monsoon winds from the continent hit the northeastern part of the island, bringing steady rain; central and southern areas, lying in a rain shadow area, have sunnier and drier winters than those in the north. During the summer, from May to September, the southwest monsoons control Taiwan’s climate; they bring rain to the south, leaving the north relatively dry.3

Tropical cyclones or typhoons rage across Taiwan three to five times a year, usually from July through September. The storms carry heavy rainfall, a major source of water for Taiwan. Their violent winds often severely damage crops and buildings.

Taiwan’s rainfall is abundant throughout the year, but it is not evenly distributed. The driest part of the island is the southwest coast, which averages 40–60 inches annually and has experienced mild droughts in recent years. The eastern coast and mountainous areas have absorbed about 148 inches of rainfall. Average rainfall is approximately 98 inches annually, and the relative humidity is 80 percent.

Summers in Taiwan are long and hot, while winters tend to be very short and mild. The annual mean temperature is higher than 70° F. There is little temperature difference from east to west, but as one travels from north to south, with each degree of latitude, the mean temperature increases 1.5° F. Winter temperatures average in the mid-60s, while summer temperatures hover above the low 80s.

Natural Resources

Taiwan has a varied endowment of resources but is richest in those considered renewable, particularly agriculture and fisheries.

Renewable resources Fertile lowland alluvial soils have supported a rich agricultural industry in Taiwan for centuries, but the types and quantities of crops produced are changing rapidly. The historical staple has been rice, both double- and triple-cropped, in which Taiwan is self-sufficient. Other crops include betel nuts, sugar cane, corn, mangoes, peanuts, grapes, watermelons, tea, bananas, and pears. Of increased importance to Taiwan’s agricultural industry are horticultural products, such as flowers, exotic fruits and vegetables, and chemical-free organic products.

Livestock production now comprises about one-third of Taiwan’s total agricultural production. Taiwan is self-sufficient in production of pork, chickens, eggs, and milk, even exporting pork to Japan.

Fish is Taiwan’s second most important renewable resource. Once, fishing was a small-scale coastal industry, but in recent years over-fishing has propelled Taiwan’s fishermen to engage in deep-sea commercial fishing, which now produces the lion’s share of Taiwan’s catches. Also, aquaculture’s role in the fishing industry has expanded recently.

The wood products industry is less important in Taiwan now than in the years immediately following World War II, when nearly 3 percent of the population earned a living by logging, lumbering, or processing wood products. Forests cover about half of Taiwan’s terrain, but most are located in less-accessible mountainous areas. Also, growing environmental consciousness has led to the withdrawal of forested lands into preserves and parks.

A final renewable resource is Taiwan’s beautiful scenery and attractive cultural fare, which drew 2.3 million tourists to the island in 1995.

Non-renewable resources Taiwan is poorly endowed with valuable rocks and minerals. The chief minerals produced on the island in the post-war period have been gold and sulphur; other mineral resources of importance include copper, salt, dolomite, and nickel. Marble has been mined near Hualien to support production of vases and other artifacts; Taiwan’s jade is considered of low quality, although it is used for some jewelry production.

Taiwan is particularly deficient in natural energy resources. Coal deposits occur in the northern parts of the island. Taiwan’s coal was sufficient to make it attractive as a coaling station in the nineteenth century; in 1996, however, coal reserves amounted to only 170 million tons, and coal comprised only 34 percent of gross power generation.4

Small amounts of oil and natural gas have been found in onshore and offshore areas, but almost all of Taiwan’s petroleum supplies are imported (70 percent from the Middle East and the remainder from Indonesia, the Congo, and Australia). Global energy crises have prompted Taiwan to reduce its use of petroleum in energy consumption from 51 percent in 1979 to 14 percent in 1995.5

Hydroelectric resources supplied much of Taiwan’s power needs during the Japanese colonial and early post-war period. However, total hydropower reserves consist of only 5,048 megawatts, of which 1,592 megawatts have been developed along several major rivers. Hydropower accounts for only 7 percent of gross power generation.6

Three nuclear power plants produce nearly 29 percent of Taiwan’s total electrical output, and this resource had become much more important by the 1980s. However, growing environmental awareness and vigorous protests against construction of a fourth nuclear power plant have brought into question the expansion of energy generation from this source.

Taiwan has not been uniformly blessed with the bounties of nature; moreover, as its industrial economy matures, it has become more and more dependent on the importation of energy resources from abroad.

The Peopling of Taiwan

Five historical processes describe the development of Taiwan’s modern population and its ethnic divisions: aboriginal settlement, foreign interest and brief occupations of Taiwan, successive waves of immigration from mainland China, Japanese colonialism, and Taiwan’s retrocession to the Republic of China upon the Japanese defeat in World War II.

Aboriginal Settlement

Archaeologists date Taiwan’s pre-history to 15,000 years ago, with its settlement by aborigines who came either from Southeast Asia and the islands of the central and south Pacific or from southern China. Their origin is reflected in aboriginal languages used today that belong to the Malayo-Polynesian family of agglutinative languages.

Although there are nine different aboriginal peoples in Taiwan, they once shared several char...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Client and Corporate State of Taiwan: 1945–1986

- 3 Transformation of the Party-State in Taiwan

- 4 Pluralism within the State

- 5 Changing Status of Economic Interests

- 6 Policy-Making in a Democratic Era

- 7 Taiwan’s Internationalization Campaigns

- 8 Comparative Perspectives on Taiwan’s Political Economy

- 9 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index