![]()

1

Introduction: Berlin becomes the Cold War espionage capital

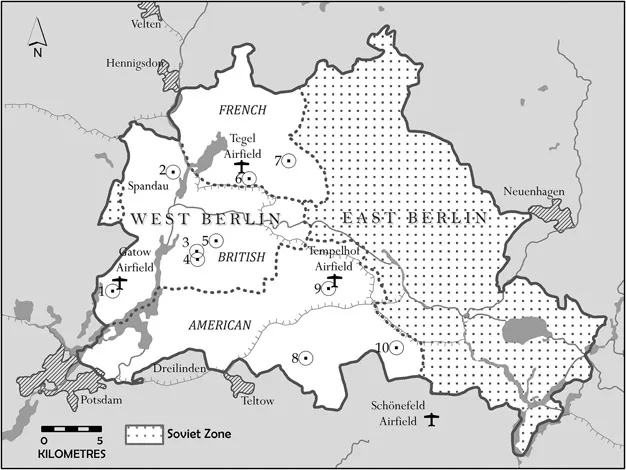

Berlin’s history is long and complex. It is a city known for its troubled past, not least over the course of the twentieth century in which legacies of the Second World War and Cold War periods have become deeply ingrained in her character (eg Ladd 1997). Nowhere is this more keenly felt than at some of the city’s key landmarks: the Jewish memorial and site of Hitler’s bunker, close to the Brandenburg Gate, and at the Topography of Terror where Nazi and Cold War remnants are juxtaposed. But it is the city’s Cold War legacies that are the subject of this book, legacies that present Berlin at the heart of European if not global Cold War history, and on the front line between East and West for much of the later twentieth century. After the end of the Second World War in May 1945, Berlin was divided into four occupation zones or ‘sectors’ controlled by the wartime allies: the United States, Great Britain, France and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Throughout the ensuing Cold War (1946–1989), the city’s strategic location between what had become East and West ensured that Berlin became the prime location for western intelligence services. (Figure 1.1).

By the 1980s, the significance of West Berlin as an intelligence-gathering centre was such that huge numbers of personnel were engaged in this activity. For example, of the 5,000 United States American military and civilian personnel in the city, 40 percent were employed in intelligence or counter-intelligence activities, additional to British and French personnel (Herrington 1999, 6). As well as military intelligence gathering carried out by the service teams, other allied security agencies, including the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the National Security Agency (NSA) and British staff from the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) also operated from various listening stations in the city. More shadowy organisations, including the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), also exploited the special position of Berlin to mount operations against East Germany (Maddrell 2012, 48). The co-location of American and British intelligence personnel at sites including the Teufelsberg was one expression

Figure 1.1 Cold War Berlin showing the occupation sectors and principal western signals intelligence-gathering sites

of the now widely known ‘special relationship’ between the two countries, cemented by a top secret pact on the sharing of intelligence signed in 1948 (Stafford 2002, 51).

Set within this wider context of complex geopolitics and regular episodes of tension, and given Berlin’s strategic location on the Cold War’s front line, this book explores the various ways in which surviving physical evidence creates opportunities for understanding a subject barely represented by available documentary and oral historical sources. This is because documents that relate to matters of continued relevance as matters of national security remain classified after the period of the ‘30 Year Rule’ has elapsed. Equally, those who worked at the Teufelsberg signed the Official Secrets Act (an Act of Parliament that cannot later be ‘unsigned’), and therefore commit an offence in speaking out, although this is more likely to be implemented in matters of strategic importance than in revealing the purpose of specific rooms within the complex. Given this lack of documentary information, and building on other archaeological studies of the contemporary past (eg Harrison and Schofield 2010) and the Cold War in particular (Cocroft and Thomas 2003; Schofield and Cocroft 2007), this study is presented specifically as an archaeological investigation of the buildings, as well as the often subtle traces within and around them, that modern military activities leave behind. Significantly, this is the first use of archaeological methods to investigate the undercover world of Cold War signals intelligence, and the first time a former intelligence-gathering site has been subjected to such close and critical scrutiny, a unique opportunity made possible only through its abandonment as an operational facility, but retention as a ruin. It is for this reason that the description of the facility is presented in close detail. In short, there may never be another opportunity.

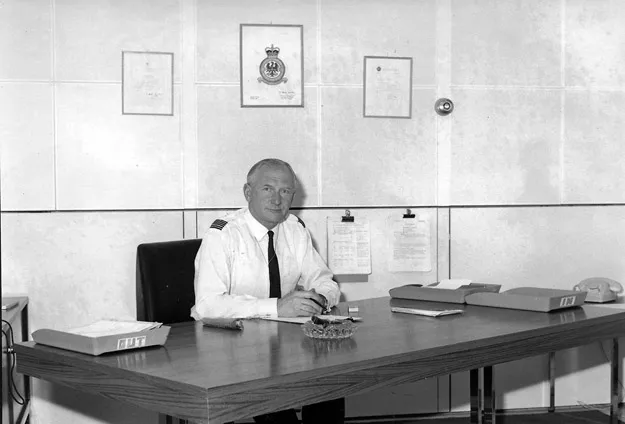

In amongst the abandoned ruins of the Teufelsberg today, we should not forget that this was also a place of work for very large numbers of people, the identities of most of whom will never be known. There are however some notable exceptions. References exist within the text to Wing Commander A E Schofield, who was Officer Commanding 26 Signals Unit in Berlin from 1971–1973, a role that involved command of the British operations at the Teufelsberg. This was John’s father. They lived on RAF Gatow during this time, and John recalls watching his father leave for work, in his black Opel with a flag on the bonnet, to his office at RAF Gatow, or on the Teufelsberg. While John was often shown the Teufelsberg as a distant landmark, from the opposite side of the River Havel, he never went closer, and his father never said anything to him or to his wife about what went on there. John’s father died in 2001 and took his knowledge of the Teufelsberg with him. Conducting field-based research on any recent site or building which has a strong personal connection gives proximity that is unfamiliar for archaeologists who typically only encounter sites of earlier periods. Archaeologists are not trained for this close proximity, which can feel uncomfortable. There is also an argument that studies and assessment of the significance of such recent places can lack objectivity for this reason, although recent developments in understanding social value within a heritage context have created more systematic frameworks for such judgements to be made (eg English Heritage 2008). John has the photograph of his father shown in Figure 1.2 on his desk, a photograph his father always told him was taken at the Teufelsberg.

John naively hoped to find this office during the project, but given the condition of the site and the changes made since his father left in 1973, this was never likely to happen. To see his signature in Operational Records Books, however, partly made up for this disappointment, while the process of conducting the research also drew them closer. A short essay about John’s time in Berlin and his connections with Gatow and the Teufelsberg has been previously published (Schofield and Schofield 2005).

Figure 1.2

Wing Commander A E Schofield, Officer Commanding 26 Signals Unit 1971–1973, reputedly in his office at the Teufelsberg

The book begins (in Chapter 2) by summarising the geopolitical context and the presence of signals and intelligence in Berlin, amongst the British, American and French forces. Chapter 3 then considers in more depth the activities of British and American units at the Teufelsberg, before going

on (in Chapter 4) to describe the archaeological approach adopted for this investigation. Chapter 5 then contains a detailed site description, presenting the only such description available for a signals intelligence site of this Cold War period. This descriptive chapter is intended to serve as a record of the site’s extant remains at the time of survey (Summer 2011), and as the basis for self-guided exploration. Chapter 6 then provides an architectural summary, before Chapter 7 explores the site’s ‘afterlife’, prior to providing some general discussion and conclusions. We begin with the start of intelligence gathering in Cold War Berlin, immediately after the close of the Second World War.

![]()

2

Electronic intelligence gathering: beginnings

All military signals units are aware that their transmissions may be intercepted, and also of their capacity to eavesdrop on the transmissions of opposing forces. From the arrival of the western allied occupation forces in Berlin in July 1945, radio operators would have been conscious of their ability to pick up Soviet radio transmissions. That said, post-war reductions in military spending had led to a rapid run down in allied wartime intelligence capabilities, and there is no evidence of any systematic attempts to analyse Soviet radio traffic collected in Berlin during the late 1940s. Even during the intense air activity during the Berlin Airlift, 1948–1949, it does not appear that Soviet activity was routinely monitored. Yet contemporary British intelligence assessments had commented that the Soviet Army used mainly landlines and was comparatively poorly equipped with wireless equipment. It also warned British units of the Soviet army’s skill in radio interception (War Office 1949, 54–55). The United States Army Security Agency (USASA) was equally poorly resourced and until at least 1949 was passing its material to the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) for analysis (Aldrich 2001, 77). From 1950 however the situation became increasingly complex, and for clarity we can divide Allied intelligence gathering in Berlin by the three allies present in the city: the British, the Americans and the French. It is also important to recognise the three main areas of activity:

SIGINT – Signals intelligence

Signals intelligence may be further subdivided into three areas:

COMINT – Communications intelligence, the interception, collection and analysis of radio, wire or other electronic communications. ELINT – Electronics intelligence, the interception and analysis of electronic signal.

RADINT – Radar intelligence, the collection and analysis of data from foreign radar, telemetry stations and beacons, and also information gathered from the tracking of aircraft, missiles and other moving objects.

PHOTOINT – Photographic intelligence

HUMINT – Human intelligence, including information provided by spies and agents, and in this case by the official western military missions operating in East Germany.

The British

British intelligence-gathering activity in Cold War Berlin was initially focussed at RAF Gatow, the British occupation force’s airfield, a former Luftwaffe training base located at the western extremity of the British occupation zone, with part of its boundary set against the sector boundary with the East. The station also acted as the parent unit for the successive signals intelligence units, covering many of their functional requirements, including accommodation. The station’s Operational Record Books provide some information on the signals units’ facilities. Elsewhere in the city British personnel also worked alongside the Americans at Rudow, Marienfelde and at the Teufelsberg.

From at least 1947, the RAF commenced a programme of ‘ferret’ flights along the Iron Curtain by modified Lancaster and Lincoln aircraft principally to gather information on the capabilities of Warsaw Pact air forces (Aldrich 2001, 81). Across the British post-war occupation zone it also maintained a network of signals intelligence stations. The RAF’s signals intelligence presence probably began with the Air Scientific Research Unit (ASRU), which was the precursor of 646 Signals Unit formed on 1 September 1952. The unit controlled all ...