![]()

Lyndal Hickey, Vicki Anderson, and Brigid Jordan

Acquired brain injury (ABI) can result from a number of causes after birth, including trauma, hypoxia stroke, infections, neurological disorders, and tumors. An ABI can cause physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and sensory impairments, which could lead to restrictions in various areas of life (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2007). Pediatric ABI is often sudden and unexpected; families are unprepared to deal with issues surrounding the injury, subsequent hospitalization, and reintegration into the home. A child’s injury can be experienced as a psychological trauma to the whole family system. It is a period of crisis and disruption for families as they support the child throughout the acute and rehabilitation phases of care while striving to meet the needs of all family members.

Rehabilitation outcomes for children with ABI are closely associated with family functioning and capacity to meet the changing needs of the injured child over time (Lax Pericall & Taylor, 2014; Ryan et al., 2015; Schmidt, Orsten, Hanten, Li, & Levin, 2010; Taylor et al., 1995; Yeates, Taylor, Walz, Stancin, & Wade, 2010; Ylvisaker et al., 2005). Families experience substantial stress and burden, depression, psychological distress, and economic disadvantage in the first 12 months following a child’s injury (Conoley & Sheridan, 1996; Gan, Campbell, Gemeinhardt, & McFadden, 2006; Stancin, Wade, Walz, Yeates, & Taylor, 2008; Wade, Michaud, & Brown, 2006; Wade, Taylor, et al., 2006; Wade et al., 2001). It is therefore vital for rehabilitation services to develop effective ways of working with families during the early stages postinjury to maximize outcomes for the child.

The social work scope of practice within pediatric rehabilitation services is to provide psychosocial interventions to assist families during the child’s inpatient and ambulatory rehabilitation. Despite the recognition in the literature of the importance of families in child rehabilitation outcomes, there is limited research about effective psychosocial interventions to promote family adaptation following the early stages postinjury (Conoley & Sheridan, 1996; Gan et al., 2006; Wade et al., 1996). Currently, there is no evidence base for effective social work interventions with families during a child’s inpatient rehabilitation phase of care.

Family Forward is currently under trial in a pediatric inpatient service at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. It is a response to the clinical and research gap about how social workers best meet the psychosocial needs of families during a child’s inpatient phase of care and transition to home. The evaluation of this intervention will contribute to ABI research and inform future social work rehabilitation practices with families as they embark on a process of adaptation parallel to their child’s recovery from injury.

This article outlines important contributions to the development of Family Forward, including research knowledge on family adaptation for pediatric ABI, a definition of family adaptation that reflects the family experience after ABI, and family therapy as a conceptual framework and practice approach. Family Forward is described using themes derived from the family adaptation definition of the resiliency model of family adjustment and adaptation (H. I. McCubbin, Thompson, & McCubbin, 1996; M. A. McCubbin, McCubbin, Danielson, Hamel-Bissell, & Winstead-Fry, 1993).

Family adaptation

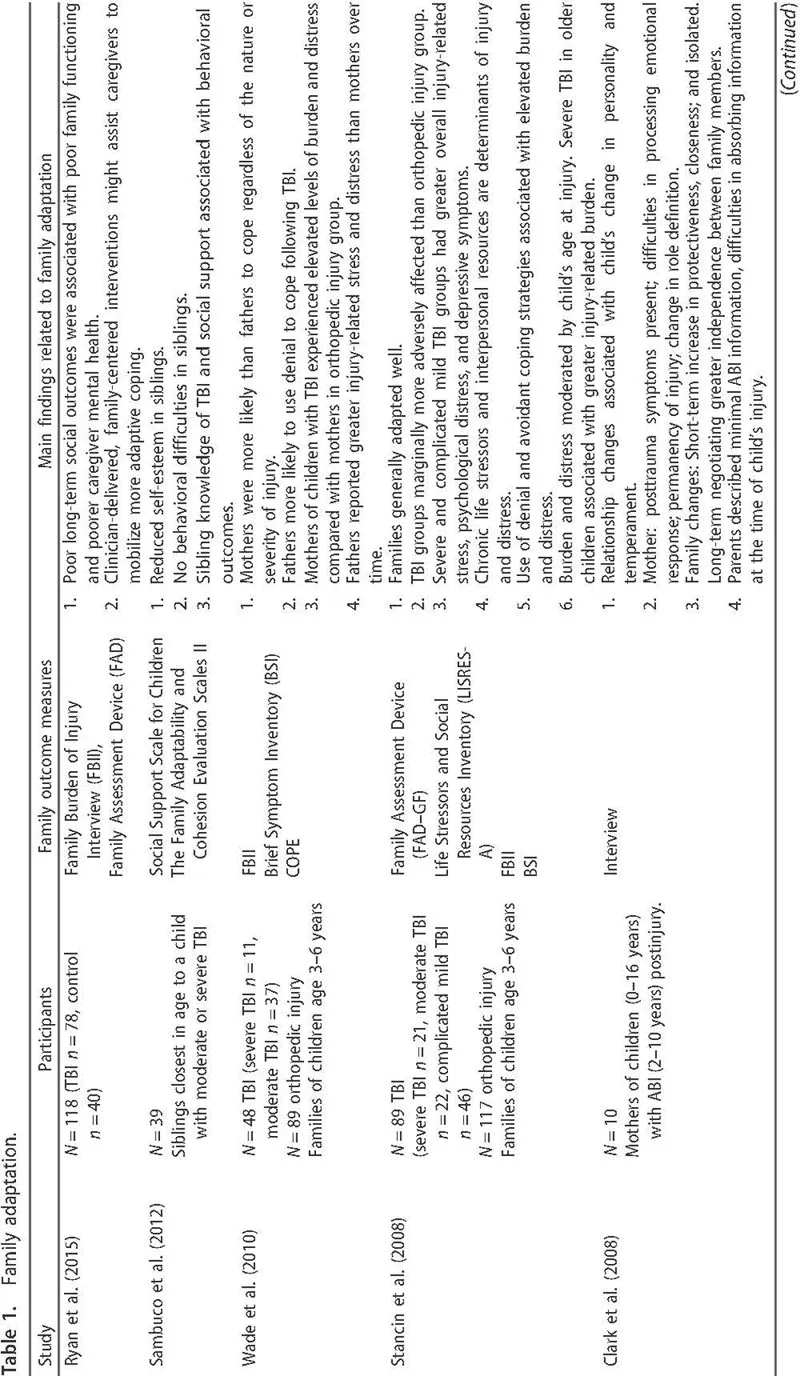

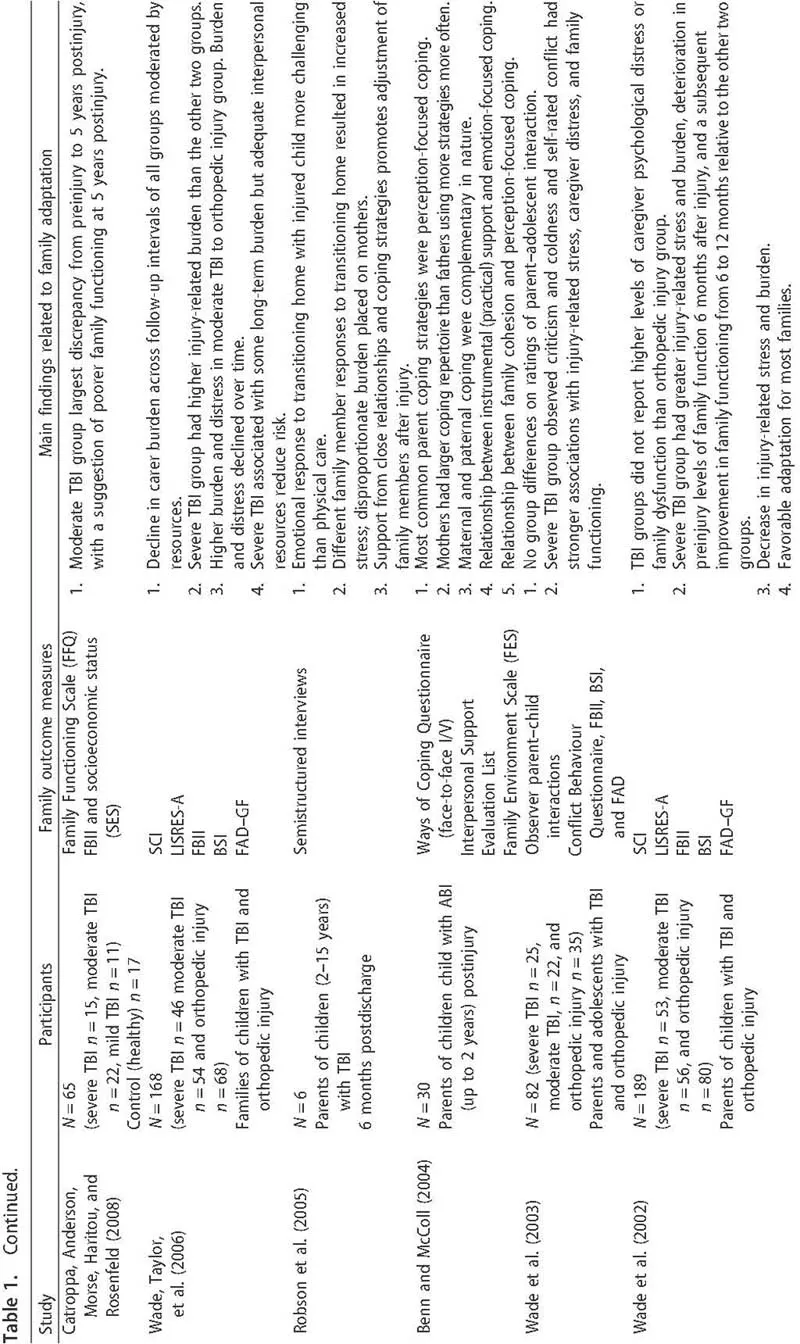

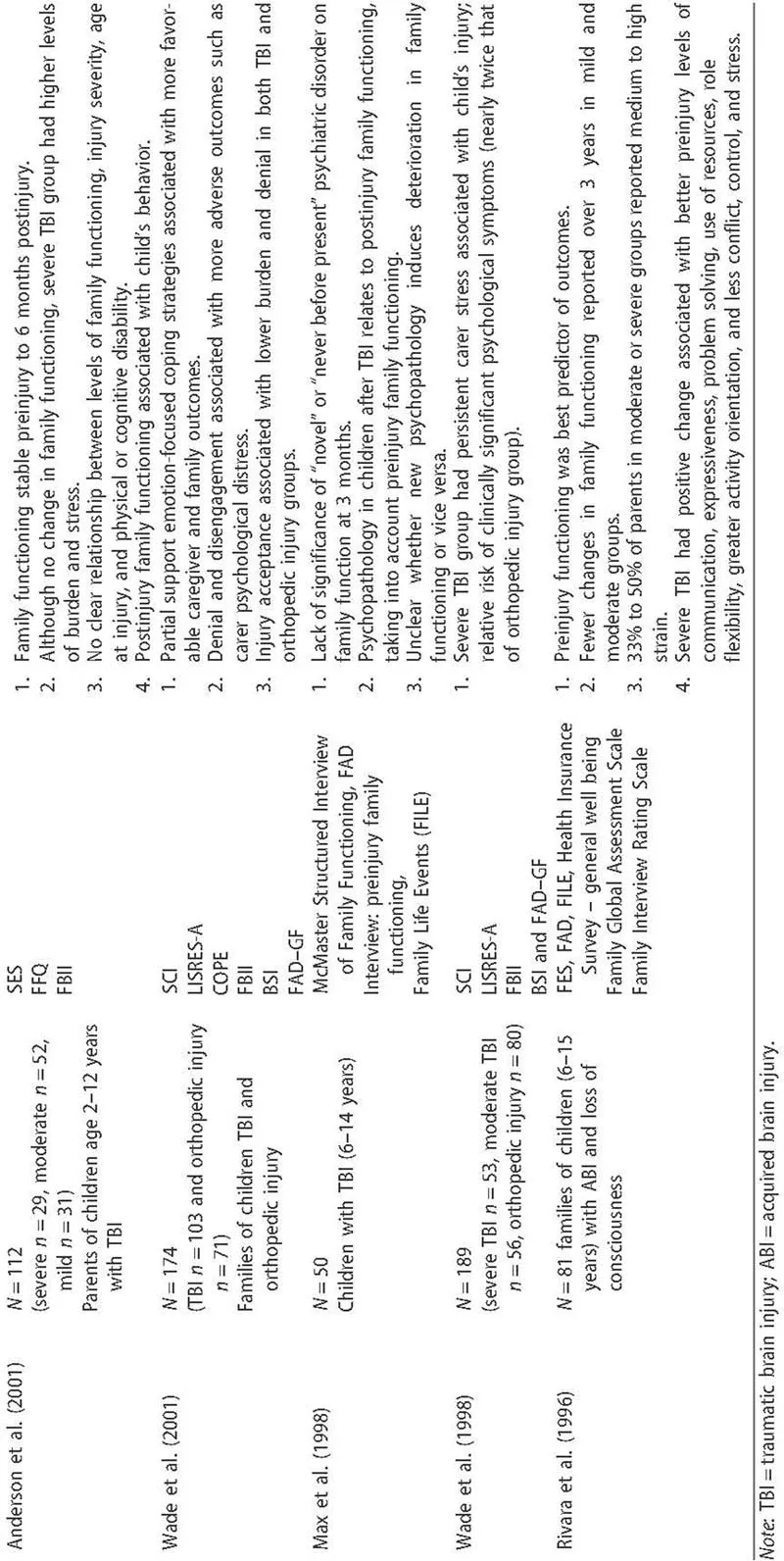

The Family Forward design has been informed by research in the area of family adaptation following pediatric ABI. The research to date has defined the adaptation process using one or two constructs such as family functioning, family burden and distress, parent coping, and predictors of family outcomes (Stancin et al., 2008; Wade, Taylor, et al., 2006; Wade et al., 1996). Quantitative studies have focused on child and family outcomes, whereas qualitative studies have explored the impact on family relationships. All relevant studies that have informed Family Forward are summarized in Table 1.

Family functioning has a significant influence on child and family outcomes. Aspects of family functioning that might alter as a result of the child’s ABI are division of day-to-day tasks, communication patterns, the amount and quality of time spent with various family members, and limit setting with the injured child (Wade, Drotar, Taylor, & Stancin, 1995). Longitudinal studies up to 6 years postinjury have found most families make the necessary adaptations to care for the injured child and restore family functioning with some variability related to injury severity (Anderson et al., 2001; Catroppa, Anderson, Morse, Haritou, & Rosenfeld, 2008; Ryan et al., 2015; Wade, Taylor, et al., 2006). Nevertheless some families have reported some deterioration in family functioning in the first 12 months postinjury, particularly evident in families caring for a child with a severe injury (Robson, Ziviani, & Spina, 2005; Wade et al., 2003). The majority of children with severe ABI are admitted to inpatient rehabilitation services during this period and tailoring interventions to alleviate challenges for this group was a key consideration for the design of the intervention described in this article. Similarly, the intervention needed to take into account key findings from the qualitative literature to assist families’ transition to home and to promote positive patterns of family interaction and relationships.

Family functioning is also associated with the development of psychopathology in the injured child in the first 24 months postinjury (Max et al., 1998). In a qualitative study conducted with families transitioning their child from hospital to home, changes to the spousal relationship and parent–child dyad with noninjured siblings were also noted. Families attributed these changes to the stresses associated with the child’s injury and prolonged periods of separation. The relationship between the parent and injured child was also affected, with parents experiencing an increased level of protection toward the child and reluctance to separate (Robson et al., 2005). Mothers interviewed several years after their child’s injury report changes in family functioning as a response to the behavioral problems of the injured child (Clark, Stedmon, & Margison, 2008).

The identification of predictors of child and family outcomes also provide important insights for how Family Forward tailors interventions and targets resources for families during the rehabilitation phase of care. Pre and post family functioning, which includes family cohesion, good communication, and better coping resources, have been found to be reliable predictors for positive child and family outcomes postinjury (Anderson et al., 2001; Max et al., 1998; Rivara et al., 1996; Stancin et al., 2008; Wade, Michaud, et al., 2006). Predictors of negative family outcomes are associated with family members’ premorbid psychiatric health and general health, families with poorly functioning households, fewer coping skills, anxiety and depression, and higher levels of stress (Max et al., 1998; Rivara et al., 1996). Chronic life stressors and interpersonal resources are also predictors of families experiencing injury burden and distress (Stancin et al., 2008; Wade, Michaud, et al., 2006), and there is a relationship between the predictors of psychosocial outcomes such as the injured child’s behavior, family functioning, and family burden. The injured child’s problematic postinjury behavior is associated with his or her preinjury behavior, increased care related to physical impairment, and family difficulties postinjury (Anderson et al., 2001).

Studies focusing on family burden, stress, and psychological distress report that families with children with ABI are more adversely affected compared with families of children with orthopedic injuries, although the differences are small (Stancin et al., 2008; Wade, Michaud, et al., 2006; Wade, Taylor, Drotar, Stancin, & Yeates, 1998, 2002). Severity of injury is also a factor in the level of stress and burden experienced by families. Families of children with severe or complicated mild injuries report greater overall stress compared with the moderate TBI and orthopedic cohorts (Anderson et al., 2001; Stancin et al., 2008).

The time lapsed since injury is also a consideration. Wade and colleagues have reported that families of children with severe TBI experience far greater stress and burden at 12 months, with a deterioration in preinjury levels of family function at 6 months and a subsequent improvement from 6 to 12 months relative to other groups (Wade et al., 2002). Several years on, families reported a decline in carer burden and stress moderated by interpersonal resources (Stancin et al., 2008; Wade et al., 1998; Wade, Taylor, et al., 2006). The findings of elevated burden and stress are important considerations for Family Forward as similar to the family functioning research; families identified at risk of increased burden and stress in the first 12 months are those with children with severe TBI, and this cohort is typically admitted for inpatient rehabilitation services.

Coping is another construct employed in research to understand the family adaptation process. Studies have defined the positive and negative impacts of coping on adaptation in relation to family cohesion, optimism, participation in recreational activities, and the subjective meaning parents give to the experience (Benn & McColl, 2004; Martin, 1988; Wade et al., 2001; Wade et al., 2010). Parents reporting positive coping tended to use strategies that altered their perception of the child’s injury; experienced differences in maternal and paternal coping as complementary; and employed emotion-oriented strategies to deal with their changed circumstance (Benn & McColl, 2004; Wade et al., 2001). Differences in coping within families can prove problematic for family adaptation, particularly in the initial period postinjury. Coping challenges have also been reported in the areas of learning about the child’s ABI, the increased amount of care for the injured child, the emotion...