Azeta Cungu and Johan F.M. Swinnen

Introduction

The Albanian agricultural reform differs from reforms in other Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) in several aspects. The starting point for the reform differed because, first the share of agriculture in total employment and output was much larger than in any of the other CEECs. Second, all agricultural land and other assets were nationalised during the Communist regime, unlike most other CEECs.

The reform process contrasted reforms pursued in other CEECs because Albania was the only country which decided to distribute all land to the rural families and farm workers. Furthermore, the implementation of the land reform and privatisation process was extremely rapid compared to any other CEECs. Moreover, the Albanian reform has resulted in a complete break-up of the collective and state farms. By 1995, all land was used by small-scale family farms - unlike any other CEECs.

This chapter describes the reform process and its outcome and analyses the factors which have influenced the reform policy choice and caused the radical restructuring of the agricultural economy in Albania. The paper is organised as follows: the first section gives an overview of the traditional land tenure rights and farm structures in Albania. Next, we discuss the post-Communist reforms in agriculture, the 1991 privatisation process, land reform and the emerging agrarian structures. In the last section, we analyse the determinants of the reform policy choices and factors which have affected the decollectivisation process.

Historical perspective of land ownership and farm organisation in Albania

The pre-transition structures of ownership and production in the Albanian agriculture are closely related to the Communist reforms which were the most radical reforms in the history of the country’s property rights. These reforms were themselves affected by the traditional farming relations and the pre-1945 structure of ownership in the Albanian countryside. In fact, one might argue that the Communist reforms which violently expropriated all landholders of more than 5 ha of land, would have been more difficult to implement had the pattern of land ownership been less polarised. With the bulk of the rural population owning little or no land at all, this radical land reform received large popular support. It is therefore interesting to have a brief look at the recent history and evolution of the agrarian relations in Albania.

Land ownership before 1945

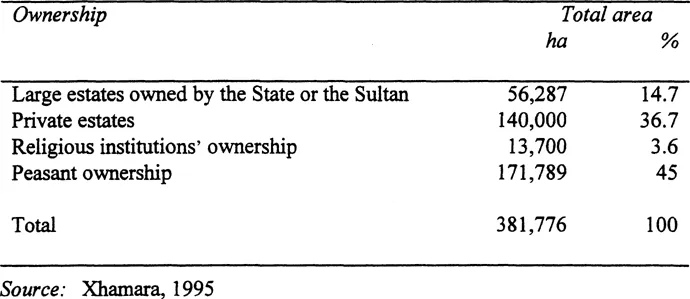

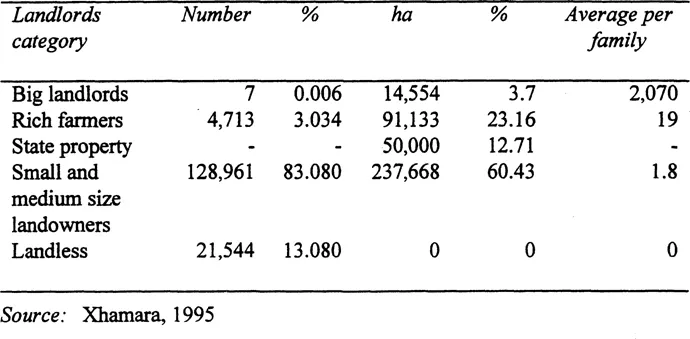

In 1912, only five families owned most of the arable land and 36.7 percent of all agricultural land (including forests and pastures) in the coastal plain and hilly region of the country (Table 1.1). After the independence from the Turks (November 1912), all land owned by the Turkish state and the Sultan was confiscated by the Albanian state, but private landowners were not affected. A land reform in 1924 tried to give 4 ha of agricultural land to each of those tilling the land but failed because of strong resistance from large landlords. Instead, the royal regime, which came into power shortly after the democratic government failed in its reform attempts, claimed that landholders’ property is ‘unviolable’. The King’s government allowed large landholders and high-ranking officials to acquire even more land by manipulation of a law for the distribution of agricultural land to Albanian emigrants returning from abroad and settling in rural areas, and by forcefully removing peasants from their lands. The King’s government distributed a few thousands of hectares of land, mostly state owned, to small and landless farmers in 1930. This reform only marginally affected the big landowners. Other factors reduced the concentration of land ownership between 1925 and 1945. The most important were land sales and estate divisions through inheritance (Civici, 1994). Table 1.2 shows how the land ownership distribution had become somewhat less unequal by 1945. However, these data do not account for differences in land quality: the inequality of land ownership was much stronger on the best quality land and peasant farms were mostly situated in the hills and mountainous areas. Furthermore, 13.8 percent of the farming population was still landless.

Table 1.1 Land ownership pattern in Albania, 1912

Table 1.2 Land ownership pattern in Albania, 1945

Communist reform and farm restructuring

The Communist economic reform started with reforms in agriculture. Soon after taking over government, the Communists launched an agrarian reform, distributing at least three hectares of average quality land to every rural family of two persons. For any additional members, 0.5 additional ha of land were granted. All large landowners and religious institutions were to be expropriated and financially compensated. This approach was not considered radical enough and an amendment ruled out compensation for all those who were not themselves farming their land. Land transactions and hiring non-family labour were banned.

Owners of large and medium sized holdings were allowed to retain 5 ha of arable land; land above this amount was redistributed to small and landless peasants (Sjoberg, 1991 quoted in Stanfield et al., 1992).

After only a few months of individual farming, the Albanian farmers were required to pool their recently acquired land into collective farms. The process was initiated on a voluntary basis in one region (Lushnja) but expanded very quickly into other areas where farmers were often forced to join the collectives. Those who did not join were labeled ‘enemies’ and became targets in the ‘class struggle’.

Collectivisation was carried out in three stages, but it was complete and radical. It was first initiated in the lowlands and later extended into hilly and mountainous areas. Alongside the process of creating the Agricultural Producer Co-operatives (APCs), State Farms (SFs) were established on the best land of the country on estates belonging to the previous state, religious institutions or big landholders. The Communist state invested substantially in modernising the state farms, which were intended to become the superior model of the socialist production structures. High quality inputs, imported machinery and other equipment, greenhouses, large storage facilities, big animal houses and selected breeding livestock were all made available to the SFs. The APCs were intended as a first step towards total nationalisation of production as their means of production were still, in theory, collectively owned. With time, it was expected that all land and assets would be state owned and APCs would therefore be transformed into SFs.

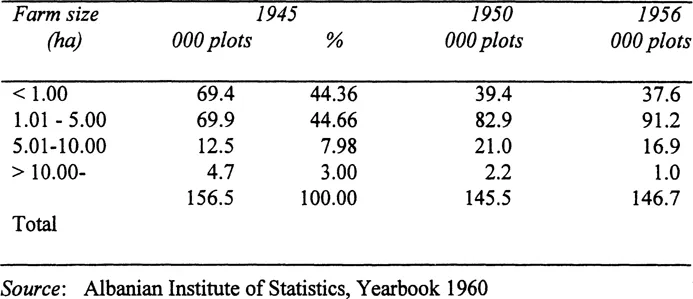

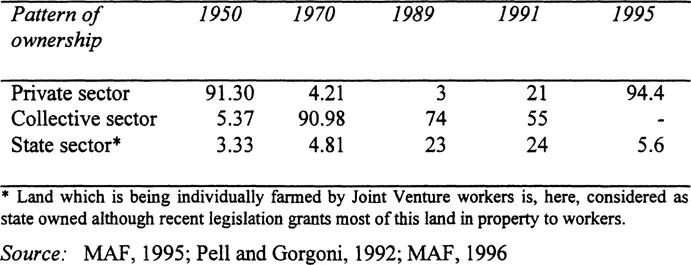

In SFs and in APCs, cropping patterns, input supplies, output marketing and sales and the structure of activities were imposed from above. The process was driven entirely by political objectives and carried out through a centralised approach. Economic considerations of profitability and incentives, efficient resource allocation and comparative advantage as well as farm specific location and climatic conditions, were less important. A characteristic feature of the period was the general trend of enlarging the collective and state farms’ scale of operations by extending the collectivisation process and reducing individual property, as well as by merging two or even more of the existing APCs together (Table 1.3 and 1.4).

Collectivisation was completed in 1967. The next step was the total abolition of private farming and nationalisation of all land. This occurred in 1976.

The pre-transition farm structure

In late 1989, some modest reforms were introduced by giving APC members small plots for individual farming: 0.2 ha in the plains and 0.3 ha in the hills and mountains (Pell and Gorgoni, 1992). However, these small plots quickly produced an important share of output: Christensen (1993) estimated that 21 percent of total agricultural output was produced by the small plots which operated on only 3 percent of the total arable land. For comparison, 160 SFs produced 29 percent of total agricultural production and owned 170,000 ha (23 percent) of arable land. Their size ranged from 500 to 2000 ha with an average size of 1,070 ha. 50 percent of production was supplied by the 492 APCs which cultivated over 74 percent of arable land. Although all land continued to be publicly owned1, most APCs were being subdivided and, by March 1991, the 492 units had increased to 1,000.

Table 1.3 Restrictions on the size of private farms, Albania 1945-1956

Table 1.4 Changes in land ownership in Albania, 1950-1995 (in %)

Despite these changes, the diversion of members’ efforts onto their private plots was detrimental for the production on land which remained with the collectives. In fact, production in 1990 and 1991 fell dramatically. The threat of food shortages and widespread economic difficulties indicated the need for much deeper reforms which would ensure a recovery of production, and a reduction of the inefficiency of the collectivised sector.

Agricultural privatisation, land reform and farm restructuring

This section summarises the main features of the current privatisation and restructuring reform in agriculture. A detailed discussion of the process and the legal framework for agricultural privatisation in Albania, is provided in Cungu and Swinnen (1997).

Privatisation and initial restructuring in agriculture

Privatisation in agriculture started spontaneously in the beginning of 1991. The Land Law (June 1991) recognised the right of APC members to receive land, in the framework of a distribution program, and leave the APC if they preferred so. This law was followed by a number of Government decrees which regulated the distribution of APC assets (other than land) as well as the complete liquidation of these structures. A number of regulations set out the procedures for the implementation of the legislation. The most important regulation was that the APCs’ land was to be divided up amongst the member families on an equal per capita basis. Specialised bodies were created to organise and monitor the distribution process at national level, the National Land Distribution Council (NLDC); at district level, the District Land Distribution Councils (DLDCs) and village level, the Village Land Distribution Councils (VLDCs). The land distribution process was formalised by issuing land ownership titles to the APC members. Besides land, other assets were also distributed amongst members once all APC debts were paid off.2 Also, Land Distribution Councils were authorised to correct the improper possession of assets which took place when villagers spontaneously broke-up the collectives.

The only exception to the above rules was witnessed in some mountain areas of the country where land distribution was not carried out according to the normal criteria of per capita allocation, but rather restituted to ex-owners in their old boundaries. The functions of the formal VLDCs were, for this purpose, performed by the so-called ‘Councils of Elderly’ which were composed of old village people known for their ‘fairness and traditional wisdom’. Families who did not own land before 1945 but who were members of the APCs and would benefit from the application of the Land Law, were thus excluded from the process. Decree No. 230, did provide some room for a de jure accommodation of what de facto had already happened in that it specified that the quantity, quality and location of...