- 340 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Breadline Britain in the 1990s

About this book

First published in 1997, this series, published in association with the Social Policy Research Unity at the University of York, is designed to inform public debate about these policy areas and to make the details of important policy-related research more widely available.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Measuring poverty: Breadline Britain in the 1990s

Poverty and politics

During the 1980s the ‘poverty debate’ became much more politically sensitive than in the past. John Moore (who was then Secretary of State for Social Security) in his speech on 11.5.89 at St Stephen’s Club claimed that poverty, as most people understood it, had been abolished and that critics of the government’s policies were:

“not concerned with the actual living standards of real people but with pursuing the political goal of equality … We reject their claims about poverty in the UK, and we do so knowing that their motive is not compassion for the less well-off, it is an attempt to discredit our real economic achievement in protecting and improving the living standards of our people. Their purpose in calling ‘poverty’ what is in reality simply inequality, is so they can call western material capitalism a failure. We must expose this for what it is … utterly false.

– it is capitalism that has wiped out the stark want of Dickensian Britain.

– it is capitalism that has caused the steady improvements in living standards this century.

– and it is capitalism which is the only firm guarantee of still better living standards for our children and our grandchildren.”

A senior Civil Servant, the Assistant Secretary for Policy on Family Benefits and Low Incomes at the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS), had made the same point more succinctly when he gave evidence to the Select Committee on Social Services on 15.6.88. He stated “The word poor is one the government actually disputes.”

Yet, despite the government’s claim that poverty no longer exists, social attitude surveys have shown that the overwhelming majority of people in Britain believe that ‘poverty’ still persists. Even the 1989 British Social Attitudes survey, conducted at the height of the “Economic Miracle” found that 63% of people thought that “there is quite a lot of real poverty in Britain today” (Brook et al, 1992). The 1986 British Social Attitudes survey found that 87% of people thought that the government ‘definitely should’ or ‘probably should spend more money to get rid of poverty’. In 1989, the European Union-wide Eurobarometer opinion survey found that British people thought the ‘fight against poverty’ ranked second only to ‘world peace’ in the list of great causes worth taking risks and making sacrifices for (Eurobarometer, November 1989). This view was widely held across the 12 member countries of the European Union, as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Worthwhile great causes

Question: “In your opinion, in this list which are the great causes which nowadays are worth the trouble of taking risks and making sacrifices for?”

Worthwhile great causes

Question: “In your opinion, in this list which are the great causes which nowadays are worth the trouble of taking risks and making sacrifices for?”

| In order of preference | UK (%) | 12 EC Countries (%) |

| World peace | 71 | 75 |

| The fight against poverty | 57 | 57 |

| Human rights | 55 | 60 |

| Protection of wildlife | 48 | 57 |

| Freedom of the individual | 43 | 39 |

| Defence of the country | 41 | 30 |

| The fight against racism | 32 | 36 |

| Sexual equality | 25 | 25 |

| My religious faith | 18 | 19 |

| The unification of Europe | 9 | 18 |

| The revolution | 2 | 5 |

| None of these | 2 | 1 |

| No reply | 1 | 2 |

Some aspects of the increase in poverty in the 1990s have become very conspicuous. The ‘problem’ of homelessness is very visible; young people can be seen begging on the streets of virtually every major city in Britain. Sir George Young (then Housing minister) even noted that homeless beggars in London were “the sort of people you step on when you came out of the Opera” (Guardian, 29.6.91, p.2). Similarly, the Prime Minister (John Major) claimed that

“the sight of beggars was an eyesore which could drive tourists and shoppers away from cities” and “it is an offensive thing to beg. It is unnecessary. So I think people should be very rigorous with it” (Bristol Evening Post 27.5.9, p.1–2)

A Department of Environment survey of 1,346 single homeless people in 1991 found that 21% of people sleeping rough said they had received no income in the previous week (Anderson, Kemp and Quilgars, 1993). The median income of those sleeping rough from all sources was only £38 per week, despite this only one fifth tried to beg. People who begged often encountered problems and begging was seen as an uncertain or precarious source of income (Anderson, Kemp and Quilgars, 1993).

The ‘poverty’ of the homeless people sleeping on the streets is shocking. An analysis of the coroner’s court records in Inner London1 indicated that the average age at death of people with ‘no fixed abode’ was only 47 (Keyes and Kennedy, 1992). This is lower than the average estimated life expectancy of people in any country in the world (not at war) with the exception of Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger and Sierra Leone (UN 1991, UNDP 1992).

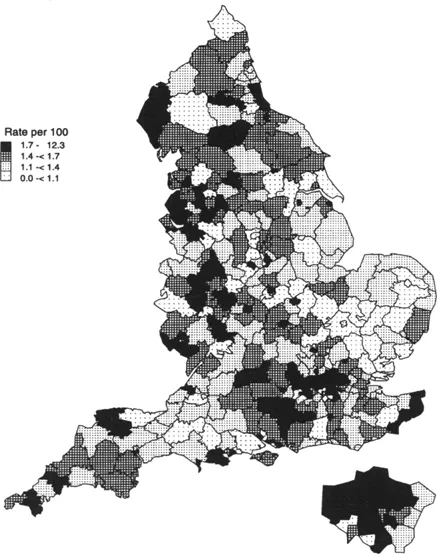

The 1991 Census recorded the numbers of homeless people in hostels, bed and breakfast and sleeping rough on census night;2 it also estimated the numbers of ‘concealed’ households. Figure 1.1 shows the rate of homelessness/housing need per 100 people (divided into quartiles) for each of the 366 local district authorities of England. A clear pattern is evident; there are high rates of homelessness in the Metropolitan districts and also in the more rural areas with little council housing, particularly in the South East (Gordon and Forrest, 1995).

Detailed analysis of the 1991 Census returns has shown that these homeless figures are just the ‘tip of the iceberg’. There are between 200,000 and 500,000 additional people with no permanent home. They are largely young men (aged 18–36), mainly in the inner cities, who move frequently and stay with friends or relatives, probably sleeping on the sofa or in a spare bed. This phenomenon of ‘hidden homelessness’ was not found in the 1981 Census (Brown, 1993).

Figure 1.1

Homeless people in hostels, bed and breakfast, sleeping rough and concealed households

Homeless people in hostels, bed and breakfast, sleeping rough and concealed households

To unders...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of tables

- List of figures and CHAIDS

- List of contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Studies in Cash and Care

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Measuring poverty: Breadline Britain in the 1990s

- Chapter 2 The poverty line: methodology and international comparisons

- Chapter 3 The public’s perception of necessities and poverty

- Chapter 4 Poverty and gender

- Chapter 5 Poverty and crime

- Chapter 6 Poverty and health

- Chapter 7 Poverty and mental health

- Chapter 8 Poverty, debt and benefits

- Chapter 9 Poverty and local public services

- Chapter 10 Adapting the consensual definition of poverty

- Chapter 11 Conclusions and summary

- Bibliography

- Appendix I: Technical appendix

- Appendix II: Annotated questionnaire

- Appendix III: Additional tables

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Breadline Britain in the 1990s by David Gordon,Christina Pantazis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.