![]()

1 The who and whys of ideological polarization

John Gerring (1997: 957, 959) notes that “few concepts in the social science lexicon have occasioned so much discussion, so much disagreement, and so much self-conscious discussion of the disagreement, as ‘ideology.’ ” Notwithstanding its “semantic promiscuity,” academics and nonacademics alike have frequently defined ideology in terms of support for or opposition to government intervention in the economy or in expanding civil rights protections to various groups. Ideology or, more accurately, policy preference is then classified along a left/liberal – right/conservative continuum for which the scope of government intervention – expanded or limited – provides the poles, a practice that has dominated such analyses for no less than 60 years.1 Based on this view, researchers have largely concluded that ideological polarization has significantly increased over the past generation both in Congress and among the public such that two distinctive, consistent sets of views are expressed on economic, social, and cultural issues. As a matter of party politics, this means that being a liberal is now synonymous with being a Democrat, being a conservative is one with being a Republican, and being a moderate holding inconsistent views is a walking “liberal Republican” or “conservative Democrat” oxymoron.

The who

Turning first to Congress, numerous studies conclude that, beginning in the 1970s, polarization has increased among legislators to a level not seen since the 1870s.2 Particularly noteworthy here is the work of Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal (1997) who in collaboration with Nolan McCarty (McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 1997) developed the NOMINATE (Nominal Three-Step Estimation) scaling method, and a related DW-NOMINATE (Dynamic, Weighted NOMINATE) procedure. NOMINATE scores are based on spatial modeling that assumes that legislators’ Yea or Nay votes are aligned with their “ideal point” on the model’s primary liberal-conservative dimension that addresses the role of the government in the economy.3 A legislator’s voting record can then be averaged and scaled to assign a score ranging from −1 to +1 on the liberal-conservative dimension (McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 2006, chap. 2). The method is used to plot legislators’ ideological positions and their positions relative to other members of Congress. Moreover, legislators’ scores can be aggregated to assign an ideological score to the two major parties that in turn serves as an indicator of polarization within a particular congressional session or across nearly the entire sweep of their histories.

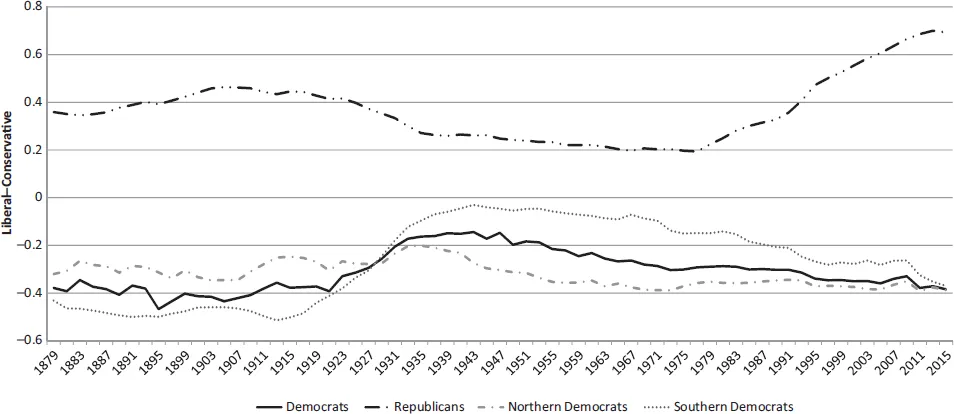

The following two figures depict changes in the parties’ ideological positioning. Turning first to the House, Figure 1.1 shows that through the 1930s to the 1960s, the ideological distance between the Democrats and Republicans remained stable and comparably narrow, suggesting that each party was dominated by moderates. Yet since the late 1970s, the distance between the two parties has increased markedly. Importantly, this polarization is almost entirely a result of growing extremism within the Republican Party. The picture in the Senate (see Figure 1.2) is similar, albeit relatively muted. From the late 1950s to the present, Democratic voting scores have gradually moved in a more liberal direction while Republican senators have moved sharply from a half century of moderate voting to more extreme positions.

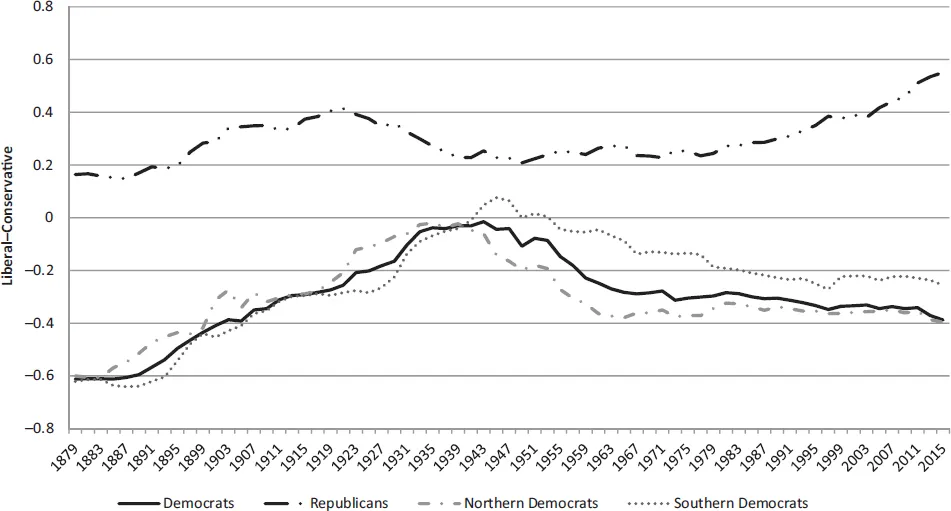

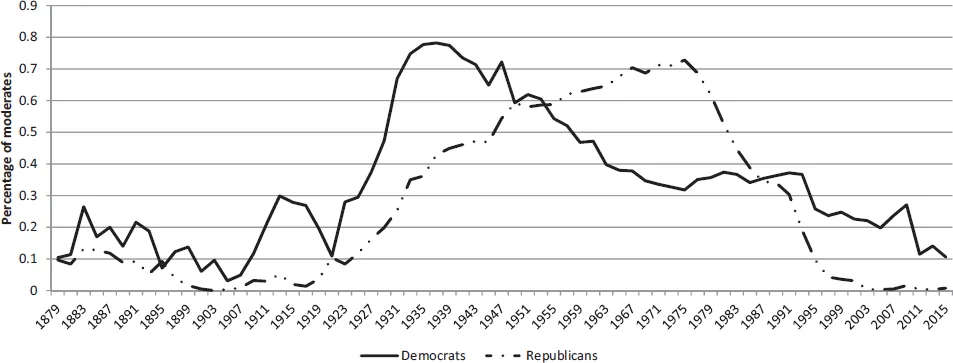

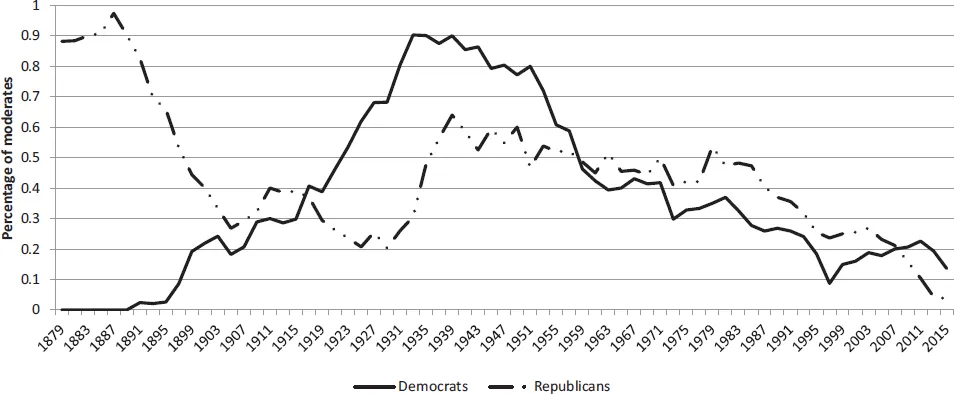

With polarization levels now at their highest since Reconstruction, it is not surprising that the number of moderate legislators has precipitously declined. In the House, Republican moderates have been all but extinct for over a decade, while only 10 percent of Democratic representatives maintained a moderate voting record in the 114th Congress (2015–2017) (see Figure 1.3). Moreover, fueled by the rise of the Tea Party movement, since 2007, 80 percent or more of Republicans in the House, compared to 10 percent of Democrats, have “noncentrist” voting scores (defined as scores that are less than −0.5 and greater than +0.5 on the DW-NOMINATE scale), demonstrating a heretofore unseen commitment to ideological purity. Contrast this to the period from the mid-1920s to the late 1980s during which time less than 20 percent of either party had noncentrist voting scores. The Senate again holds to this same pattern, with a trend toward more ideological consistency and a decline in moderates, most notably among Republicans, since the late 1970s (see Figure 1.4). At its peak level in 2015, just over 60 percent of Republicans had noncentrist voting records, a pattern evidenced by only 10 percent of Democratic senators (Poole and Rosenthal n.d.).

Legislators’ voting records demonstrate that increasing polarization has been the product of growing extremism within the Republican Party (e.g., Grossman and Hopkins 2016; Hare and Poole 2014; Parker and Barreto 2013; Skocpol and Williamson 2013; Kabaservice 2012; McCarty et al. 2006; Hacker and Pierson 2005). Mann and Ornstein argue that the asymmetric extremism of the party is a primary reason for today’s dysfunctional government. In their bestseller, It’s Even Worse Than It Looks, they contend that the mainstream Republican Party:

Figure 1.1U.S. House 1879–2015: Party means on liberal-conservative dimension

Figure 1.2U.S. Senate 1879–2015: Party means on liberal-conservative dimension

Figure 1.3Percentage of House moderates, 1879–2015

Figure 1.4Percentage of Senate moderates, 1879–2015

has become ideologically extreme; contemptuous of the inherited social and economic policy regime; scornful of compromise; unpersuaded by conventional understanding of facts, evidence, and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition, all but declaring war on the government.

(2012:103)

And with the ensuing years offering no reasons to celebrate, the authors lamented in their sequel, It’s Even Worse Than It Was, that the Republican Party “has become so radicalized… [i]t is as if one of the many paranoid fringe movements in American political history has successfully infected a major political party” (2016:xv).

The whys

Given that historically high levels of ideological polarization are due almost entirely to the extremism of the GOP, the question begged is why? While pinning down the causes of Congressional polarization is messier than marshalling evidence for its existence, the various factors explored by scholars can be divided into two broad and recursively intertwined categories: (1) those that focus on institutional shifts within the political domain narrowly defined and (2) those that focus on broader societal changes and pressures emanating from the electorate. In the following sections, I briefly review some of the more frequently discussed causes.

Institutional shifts

The Civil Rights movement altered the reigning New Deal electoral coalition that brought the Democratic Party to legislative power during the 1930s by suppressing regionally based dissension on the issue of racial segregation. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act the following year, both spearheaded by a Democratic administration, the party’s stranglehold over Southern states began to loosen (Jacobson 2000; Layman, Carsey, and Horowitz 2006; Rhode 1991; Roberts and Smith 2003). As newly enfranchised black American voters were overwhelmingly identifying with the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, led by Barry Goldwater’s failed 1964 presidential campaign and Richard Nixon’s so-called Southern Strategy, was primed to market itself as a new home for white, conservative, Southern voters disaffected by the Democrats’ evolution on racial and cultural matters.4 Electorally speaking, the GOP’s strategy has proved a success. In the 88th Congress (1963–1965), Republicans in the House accounted for 13 percent of the representatives from the 16 Southern states. In the 116th Congress (2019–2021), Republicans make up nearly 65 percent of Southern representatives. The Reagan revolution of the 1980s and the Republicans’ recapturing of the House in 1994 after some 60 years of being in the minority further solidified the party’s pull toward economic and social conservativism.

In developments that have had greater impact on the GOP, from the late 1970s onward, previously cross-pressured or moderate politicians have been disappearing as the processes of “replacement” and “conversion” have either led to electoral victories for the more extreme candidate or, in the case of conversion, prompted politicians to switch parties as a matter of electoral strategy or as a result of pressures from party leaders to conform to party orthodoxy (Fleisher and Bond 2004). What remains is a “conditional party government” comprised of more disciplined partisans who are more likely to vote along ideologically distinctive party lines and more inclined to grant additional powers to their party and its leadership (Aldrich and Rhode 1997, 2000; Aldrich 1995; Rhode 1991; see also Theriault 2008).

For the majority party, this provides essential institutional leverage to its leaders for shaping policy outcomes that are more in line with the party’s own center of gravity (Aldrich and Rhode 2000).5 For instance, party leaders are able to appoint loyalists to those committees seen as most critical to the party’s policy ambitions, add “bonus” seats to those committees, and even substitute committee members on an ad hoc basis to ensure the desired outcomes. And for committee members who need to be sold on the party’s position, leaders can allocate pork barrel funds to the congressperson’s district. Relatedly, party leaders can derail bipartisan outcomes by calling for a second vote on settled agenda items, scheduling a vote during a time when dissenters are unlikely to be present, and pulling legislation from consideration on the floor when unsure of having secured the votes necessary for its passage (ibid.). The latter tactic was employed by House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) in the spring of 2017 and later by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) when each pulled the Republicans’ health care plan from consideration when it became clear they did not have the votes to pass it.

Party leaders, however, do not hold all the cards. Given that a main objective of the Speaker is to produce a legislative record that will best guarantee his party’s majority status, more extremist members of the party can move the agenda further from the center as a condition for securing their votes (Aldrich and Rhode 2000; Grossman and Hopkins 2016). In effect, majority party leaders have to navigate not only the minority party’s opposition but also opposition from ideologically strident members of their own party, an effort complicated by campaign financing laws that steer contributions to candidates as opposed to parties (Issacharoff 2017). With members of Congress now able to act “as independent entrepreneurs and free agents,” a key mechanism for enforcing and rewarding party loyalty is lost (Pildes 2014:830). The difficulties of walking this tightrope were evident in the case of John Boehner (R-OH) who quit his position as Speaker and left the House in 2015 due to the intransigence and ideological extremism of his party’s Freedom Caucus that saw even the hint of compromising with Democrats and President Obama as an act of treason.

While Democratic Party leaders are not immune from threatening retribution for those who fail to tow the party line, Newt Gingrich (R-GA) has few peers when it comes to demanding party fealty. In 1983, Gingrich spearheaded the creation of the Conservative Opportunity Society. As part of its single-minded attempt to defeat Democratic incumbents, the group called for the party to withhold its cooperation with their rivals at every opportunity. Opposition, not compromise was their raison d’être (Roberts and Smith 2003; Mann and Ornstein 2016). Indeed, “reflexive partisanship” has led legislators to oppose proposals simply “because it is the opposing party’s president that advances them” (Lee 2009:4). Particularly when faced with the prospect of close elections, members of both parties are incentivized to adopt opposing positions on all matters of legislative procedure and policy, even those for which there is no clear ideological division, in order to accentuate partisan differences. As legislators adopt more extreme views and call attention to new issues, they provide cues for voters, allowing them to better align different policy positions as well as their own ideological positions with a given party (Layman, Carsey, and Horowitz 2006:95).6 With partisan voters more likely to change their beliefs than their party (Campbell et al. 1960; Pildes 2011:293; see Sundquist 1983 for an opposing view), the fusion of ideology and party affiliation in the electorate then reinforces the extremism of politicians who adopt polarizing views as a means to secure the support of their core electoral constituents (Galston and Nivola 2006:18).

The “teamsmanship” (Lee 2009) that breeds additional points of confrontation and encourages members of Congress to institutionalize and exacerbate existing partisan divisions (Barber and McCarty 2013) has morphed into a “rule or ruin” strategy that has converted the modern GOP into the party of “no” and left it ill equipped to craft and pass major legislation. Perhaps the best evidence for their fecklessness (and ideological posturing) is again the Republican-led House’s inability to propose a viable health care plan despite holding over 50 votes to repeal the Affordable Care Act (2010) and having eight years and counting to develop an alternative to it. And though the Senate is considered the more staid chamber, reflexive partisanship is not foreign to its members. For instance, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s (R-KY) refusal to consider President Obama’s nomination to the Supreme Court and his later decision to employ the “nuclear option” that allowed the nomination of Neil Gorsuch to proceed on a simple majority vote, upended centuries of tradition and eliminated the Democrats’ ability to filibuster Gorsuch’s appointment to the Court. Yet McConnell was only extending that tactic to its logical conclusion. Four years before, then Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV), in the face of historic levels ...