This chapter considers the wider context within which the Henley Project was planned and developed. It discusses known links between high child protection referrals, other evidence of harm to children and aspects of disadvantage. Policy and legislation which fosters an active approach to preventive work, family support and promoting wellbeing is referred to. Some approaches which have had success in preventing harm and the principles on which they have been based are discussed. The value of community wide, interdisciplinary strategies is emphasised.

Links between disadvantage and harm to children

The social and economic circumstances of substantial minorities of families are associated with difficulties in bringing up children in health and safety. Childcare problems including high child protection referrals, are common in areas where there are high crime rates, poor school attendance, under achievement, drug use, teenage pregnancies. (Wilson and Herbert 1978; Brown and Madge 1982; Wedge and Essen 1982; Brown 1982; Becker and MacPherson 1988; Chamberlin 1988; Bebbington and Miles 1991; Blackburn 1991; Baldwinand Spencer 1993; Sedlak 1993; Spencer 1996; Reading 1997; Parton 1997). All these problems are associated with major social and economic disadvantages. Family breakdown and stress are closely linked to multiple deprivations in income, employment, housing, education and health (Court report 1976; NCB 1987 and 1992; Chamberlin 1988; Schorr 1988; DoH 1992; Graham 1993). Loneliness, stress, social isolation and vulnerability to mental health problems are particularly common for women with young children (Blackburn 1991) and are also associated with disadvantage.

Infant mortality in the United Kingdom is higher than in most other European countries and inequalities in children’s health are substantial (NCH 1992; Spencer 1996; Reading 1997). High rates of low birth weight, infant mortality and poor health outcomes within countries are concentrated in the groups and regions with lowest incomes.

Children between 1 and 15 years in England and Wales are twice as likely to die in social classes IV and V as in I and II (Blackburn 1991). In England and Wales:

Not all parents are assigned a social class in official figures, for example, single mothers who have never had a job. Reading draws attention to the implications of this for the real social differences:

Inequalities in child health are greater in countries with wide differences in income — such as the USA — than in countries where there are narrower differences in income between social classes — such as Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark (Reading 1997, p. 464)

There are also striking differences across Europe in the availability of publicly funded childcare services, which might be seen as providing a measure of support for families and children, and which are associated with educational and other advantages in later life (New and David 1985). Between 35 and 40% of children aged 3-5 years have access to publicly funded childcare services in the UK, compared with 85% in Denmark and more than 95% in France and Belgium (NCH 1992).

There is a close correspondence between disadvantage and many aspects of harm to children (Schorr 1988; Utting 1993 and 1995; Baldwin and Spencer 1993; Roberts et al. 1995; Tennant 1995). Following major studies into possible ‘cycles of deprivation’ Brown and Madge (1982), concluded that the evidence showed that various aspects of harm and social and educational disadvantage were closely connected with the limitations imposed by adverse economic circumstances. The effects of adverse economic circumstances may persist over generations (Brown and Madge 1982; Brown 1983).

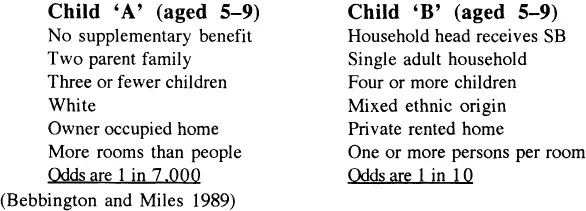

In their study of the circumstances of children who come into public care, Bebbington and Miles (1989) showed huge discrepancies between the likelihood of children in advantaged circumstances and those in disadvantaged circumstances coming into care.

Table 1 Likelihood of children in different circumstances coming into the care of the local authority

They also showed that living in areas with high rates of poverty had an independent influence, over and above that related to individual circumstances.

In Strathclyde 78% of children who came into care between 1985 — 92 were from families on benefits (Tennant 1995).

The fact that children of mixed racial heritage are exceptionally likely to come into care may reflect inordinate stresses within family groups where the racism, prejudice and inequality common within society enter into every aspect of life. It may also be connected with discriminatory processes and attitudes of agencies and professionals with responsibility for assessing the needs of children. More research is needed in this area. Meanwhile, it would appear that particular attention is needed to provide support for such families, in ways which will avoid stigma.

Black families are particularly likely to suffer material disadvantages and social injustice and to have to cope with added stresses because of individualised prejudice, harassment and abuse (Devore and Schlesinger 1987; Blackburn 1991; Cook and Watt 1992).

The Booths’ study (1994) showed that mothers and fathers with learning disabilities are particularly vulnerable to intervention in their lives and the removal of their children from home. They too are likely to be materially disadvantaged.

NSPCC figures for the circumstances of children on child protection registers show very strong correlations between economic disadvantage and registration for child abuse and neglect. The forms used for registering children asked for approximate weekly income of families, but this was recorded for less than a quarter of those registered, so was not analysed. However, over half of all the registered children’s families were recorded as in receipt of supplementary benefit. Over three quarters of the cases registered for neglect and failure to thrive were in receipt of benefit. (NSPCC 1987). In 1990, only 13% of mothers of children registered were in paid employment. Where there was a father in the family, 40% were unemployed (NSPCC 1990).

The percentage of parents whose employment status put them into the higher social class categories used by the Registrar General was so low that figures were combined in the NSPCC analysis. Social classes I and II were combined with the non manual occupations of class III. Only 4% of mothers of children registered were in this combined group, and only 5% of fathers. 1% of mothers and 11% of fathers were in occupations classified as Social Class 3 — manual. Compared with the population generally, semiskilled and unskilled occupations were heavily over represented. Debts were recorded for 25% of families on the registers. Of those registered for failure to thrive and neglect, 45% were recorded as having debts. (NSPCC 1987 and 1990) Some of the poorest families (Reading 1997) do not appear in a category at all — as mentioned under aspects of health and mortality earlier.

In a comprehensive study of the circumstances of children on Child Abuse Registers in America (Sedlak 1991 and 1993), low income was a powerful variable associated with abuse of all kinds. High income was a protective factor (Pelton 1994).

Interpretation of the data is complicated by the methods of collection, differing definitions of what constitutes abuse and neglect and the policing and social control role of professional childcare agencies. Nevertheless, the association between disadvantage and harm to children is so strong as to suggest that attention to economic factors is crucial in planning child protection strategies (Baldwin and Spencer 1993; Melton and Barry 1994; Parton 1997). When the individual harm suffered by children who are placed on child protection registers is looked at in parallel with other aspects of harm — ill health, poor school attainment, crime, drug abuse — associated with the disadvantaged neighbourhoods in which most of them live, the multiple chances of harm for some children become strikingly clear. In our view, these figures support the claim that adverse economic circumstances and the problems of living with inadequate resources severely limit the capacity of families to provide a nurturing and protective environment for their children. They raise questions about whether children in such families and neighbourhoods should be considered as ‘in need’ or ‘at risk of significant harm’ under the Children Act 1989, and Children Scotland Act 1995 (Baldwin and Spencer 1993; Melton and Barry 1994; Tuck 1995 and forthcoming; Sinclair et al. 1997).

In drawing attention to some of the statistics showing links between harm to children and aspects of disadvantage, we want to take care not to stereotype and further stigmatise disadvantaged groups. Whilst asking questions about the resources needed for families to provide a healthy environment, we want to pay attention to the strengths, skills and commitment of families and be aware of differences in family values, patterns of child rearing and cultural and religious priorities. Our approach to families as experts on their own situations is based on respect for difference and a view that families want the best for their children (Wilson and Herbert 1978; Mayall 1986; Blackburn 1991), without denying that serious harm can and does take place within families. The principles of the United Nations Convention and the Children Acts allow attention to be paid to the interconnected needs of children and families, without deviating from a commitment to the child’s welfare as paramount and without allowing a ‘rule of optimism’ (Dingwall et al. 1988) to obscure potentially conflicting interests. The Henley Project was concerned to bring together the views of parents living in an area of disadvantage, about what would be helpful in protecting children, with knowledge gained from other projects which had been successful in preventing harm, to move toward positive strategies for services to children and families in the neighbourhood. We started from an ecological approach, seeing the child and family within wider social and economic contexts (Garbarino and Sherman 1980; Whittaker 1988; Schorr, 1988; Chamberlin 1988; McGuire and Shay, 1994; Melton and Barry 1994).

In exploring the value of community wide strategies of family support and prevention of harm, we do not wish to suggest that the major inequalities associated with the conditions in which crime and abuse flourish are unchangeable. Policies which allow deprivation and harm to continue need analysis and challenge. This wider political commitment is closely linked to the project’s aim to explore the most effective ways of combating current problems associated with disadvantage. Holman (1988) has argued that social work responses to problems of children and families have traditionally been based on a rescue approach, frequently offered only when family conditions and coping mechanisms are breaking down. To focus only on emergencies and on the responsibilities of parents whilst ignoring the wider context would be to deny the facts amassed over decades. Political action for social and economic change is needed at all levels. However, there is now a body of work which demonstrates that the worst consequences of multiple disadvantages can be lessened by community and family supports (Chamberlin 1988; Miller and Whittaker 1988; Schorr 1988; Gibbons et al. 1990; Gibbons 1992; Zigler and Styfco 1993; Melton and Barry 1994).

Welfare services which are geared to rescue approaches and crisis intervention cannot give adequate attention and emphasis to the supports needed by families. Nor can they draw on the strengths, skills, resources and expertise within communities. We emphasise the value of changing to a more supportive and preventive approach at the same time as urging a commitment by Government agencies to a more realistic approach to the needs of families and neighbourhoods. Planned approaches which facilitate self help initiatives, many of them at relatively low cost, need much greater attention.