![]()

Chapter One

PLACING MEDICARE IN CONTEXT

Medicare has contributed substantially to the well-being of America’s oldest and most disabled citizens. It is the largest public healthcare program in the United States, providing the major source of insurance for acute care for the elderly and disabled populations. For some, Medicare represents a model of what national health insurance could be in the United States. Its administrative costs are low, and it is popular with both its beneficiaries and the general population. At the same time, Medicare is one of the fastest growing programs in the federal budget, gobbling up new resources at the rate of 15 percent each year during its first 30 years. Critics assail the program as being out of sync with the needs of many senior citizens through its failure to provide long-term care coverage. It is the subject of endless criticism and debate by physicians and hospital administrators, who nonetheless rely upon it for a substantial share of their revenues. Some proponents of change would fully privatize the program, but most proposals to privatize Medicare would retain the current program as a fallback.

In 1995, Medicare consumed $177 billion in federal outlays. Nearly every year since 1980, it has been a major focus of budget reduction efforts. And in 1995, projected seven-year savings of $226 billion made it the largest component of savings in the Balanced Budget Act, which was vetoed by President Clinton. The controversy over the appropriate size and funding for the program will continue for the foreseeable future as the pressures on financing the program grow. This book examines the current status of Medicare and offers options for reform with a particular focus on the program’s beneficiaries: What is Medicare, how does it work, and where is it headed? What are the problems facing Medicare, and how can they be resolved? What options for the future hold the most promise?

WHY EXAMINE MEDICARE NOW?

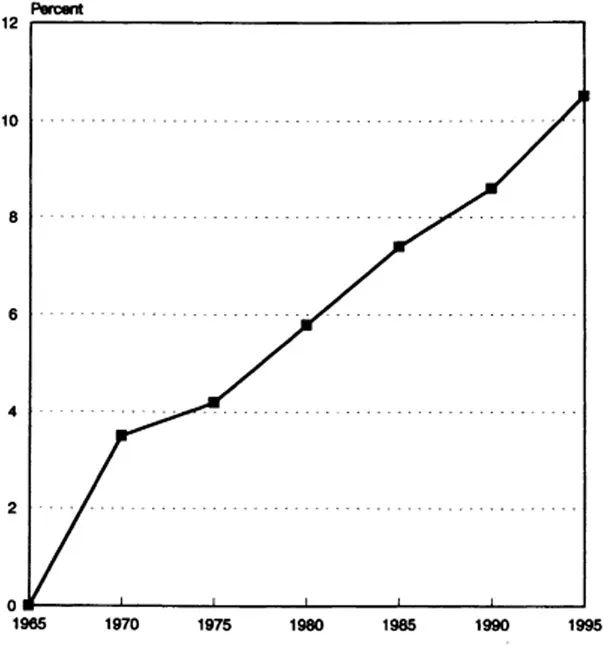

The portion of the federal budget devoted to healthcare has been expanding rapidly since 1965, when Medicare was introduced as a program to meet the healthcare needs of aged Americans. Critics pointed out early on that Medicare spending was likely to grow rapidly; and grow it did. For example, in 1970, spending on Medicare totaled $6.8 billion, about 3.5 percent of the total federal budget. Twenty years later, that share had more than doubled as Medicare accounted for 8.6 percent of the federal budget and about $107 billion in outlays (U.S. Congress, House Committee on Ways and Means [henceforth, Ways and Means] 1991) (see figure 1.1). By 1995, the share had grown to 10.5 percent of the budget (Office of the President 1996).

This rapid increase is outstripping the growth in dedicated revenues to support the hospital portion of Medicare. In 1995, payments out of the program exceeded revenues coming in, signaling the inevitable exhaustion of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund if no policy changes are made.1 After postponing the date of reckoning consistently for years—by undertaking various cost-cutting efforts and increasing the wage base subject to taxation—the latest Medicare trustees report predicts the date of exhaustion to be 2001 (Board of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund [henceforth, HI Trustees] 1996). The trustees’ report for 1996, as it has for several years, indicates that the fund does not meet the short-run test for solvency.

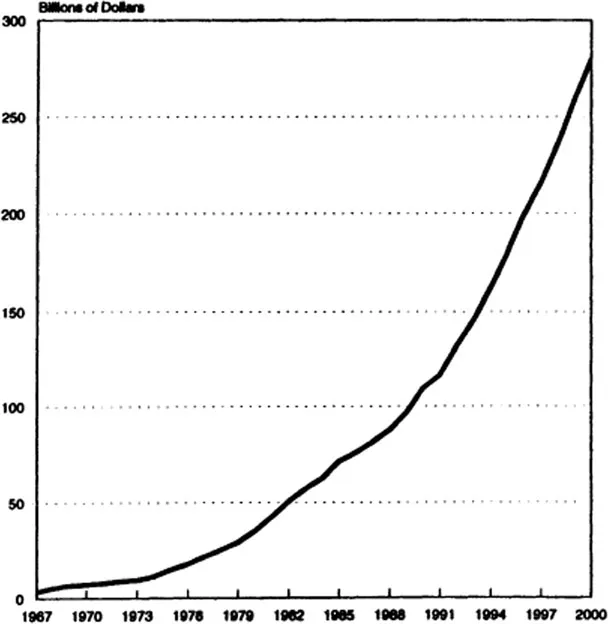

Because of its size and rapid growth, Medicare also became a target of budget reduction efforts, beginning in earnest with the administration of Ronald Reagan. Every budget submission by Presidents Reagan and George Bush contained proposals for substantial cuts in Medicare. Many of those cost-containment changes, particularly in the area of provider reimbursement, were enacted by the U.S. Congress in the 1980s. The budget reduction efforts of President Clinton in 1993 cut Medicare spending by $56 billion over a five-year period. Budget stalemate in 1995 precluded further changes. But both sides of the political aisle agree that more spending reductions will be needed since Medicare has continued to expand. Any legislative cuts have been more than outweighed by spending growth. In Medicare, “cuts” of even billions of dollars do not mean declines in spending—just a slower rate of increase (see figure 1.2).

Because Medicare is such a large component of the federal budget, it receives particular scrutiny for further sources of budget reductions. Further, most of its enrollees are over age 65, and in the last several years, the growing share of the budget devoted to older Americans has been noted with alarm by conservatives and liberals alike. Some claim that more resources should be freed up for children, others that too much public money is spent on the elderly.

Figure 1.1 MEDICARE AS SHARE OF FEDERAL BUDGET, 1965–95

Source: U.S. Congress, House Committee on Ways and Means (henceforth, Ways and Means) (1994); Office of the President (1996).

At the same time that much of the focus in Medicare has been on reducing spending, critics argue that the program inadequately meets the needs of the aged and disabled. Medicare’s coverage is less generous than that offered many younger families and individuals through employer-subsidized insurance. The ill-fated Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988 sought to fill in some of those gaps, but that legislation was repealed just 18 months after passage. The failed attempts to enact comprehensive healthcare reforms in the early 1990s would not have expanded Medicare, but did propose a modest program to meet some of the long-term care needs of elderly and disabled persons. Although this would have been a separate program, supporters of expanded long-term care benefits often seek to add such coverage to Medicare.2

Figure 1.2 ANNUAL FEDERAL OUTLAYS FOR MEDICARE, 1967–2000

Source: Office of the President (1996).

In many ways, Medicare was of only secondary concern in the debate over broader reform from 1992 to 1994. Medicare would have largely been kept separate from other reforms, and was treated as “untouchable” even by those advocating sweeping changes elsewhere (Moon 1994). Less popular approaches would have folded Medicare into a fully public system, or “privatized” it to conform to a similar market-based reform plan for younger families. But while the collapse of general health reform proposals in the first half of the 1990s has meant little discussion about change for the general population, interest in Medicare has actually increased. But the new concern stems more from discussions about downsizing government than from interest in Medicare per se.

Four areas of pressure will shape the future of Medicare. First, Medicare was established to help the elderly, and then disabled persons, to afford medical care. Thus, the economic status of these two groups—and particularly the elderly—is a critical factor in assessing how the system ought to change. Second, what happens in the healthcare system overall clearly affects Medicare. In many ways, the problems facing Medicare are but a reflection of the broader problems facing healthcare in the United States. Most observers agree that at least some of the solutions to Medicare’s problems should apply systemwide, although systemwide reform efforts seem less likely than just a few years ago. Third, Medicare’s future as a public program is tied to the financing problems facing the federal government during a period of fiscal restraint. So long as budget deficits continue at the federal level, changes in Medicare will be caught up in the pressure to limit all types of federal spending. Finally, the demographic changes looming on the horizon—which will swell the ranks of those eligible for benefits and diminish the number of workers financing the system—are beginning to influence the debate even about Medicare’s near-term future.

ECONOMIC STATUS OF OLDER AMERICANS

By every measure of economic well-being, the situation for older Americans has improved substantially over the past three decades. For example, incomes for those 65 and older have risen steadily, from a median per capita income of $3,408 in 1975 to $10,808 in 1993 (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1991 and 1996). After controlling for inflation, this represents a gain of 18 percent in the purchasing power of this age group. Moreover, in the 1980s, the elderly’s income growth outstripped increases in income for younger subgroups of the population. Although average before-tax incomes for elderly families still lag behind those of younger families, after adjusting for differences in family size and tax liabihties, the disposable (posttax) per capita incomes of older Americans do not differ substantially from those of their younger counterparts (Danziger et al. 1984; Smeeding 1986). Income growth in the 1990s seems to be proceeding similarly for both the young and the old.

But to fully comprehend the ability of elderly individuals to meet their needs, it is crucial to look beyond averages and to understand the diversity of the resources available to this group. Although the elderly have shown impressive gains as a group, not every elderly individual has shared in the good fortune. For example, some of the increase in well-being associated with comparisons of incomes across time reflects the changing composition of the elderly. Each year individuals turning age 65 join the elderly “category,” and the incomes of new cohorts of 65-year-olds tend, on average, to be higher each year. As a result, individuals within the elderly population display much slower rates of income growth than does the group as a whole. For example, as shown in table 1.1, growth in median incomes for all persons 65 and over averaged 7.1 percent for men and 4.9 percent for women between 1985 and 1990 (after controlling for inflation). But if, instead, we followed the cohort of persons aged 65 to 69 in 1985 (who were 70 to 74 in 1990), incomes rose much more slowly and actually declined for men.

On a more positive note, elderly poverty has declined. The share of the elderly in poverty dropped from 25 percent in 1968 to 11.7...