![]()

1 Introduction

KAREN VORST

The events that have taken place in Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies since 1989 have had a tremendous impact on the lives of individuals, on the operations of businesses and on the activities of governments. It is a whole new economic world for most participants who previously had known only the Soviet/Communist system with its central planning and control over the means of production. The economies that embarked upon the journey to a market system have had to make a great number of changes along the way. Governments have had to be willing to relinquish their tight control in many areas, including production quotas, wage rates, the distribution of goods and services, currency convertibility, and ownership of property. Surviving businesses have experienced significant changes in their operations, weeding out the old techniques and struggling to conform to the new standards and technologies. Individuals have witnessed the availability of a wider variety of goods and services, though prices are higher and job security is lower. Countries have embraced a system that is imperfect itself and have tailored it to suit their individual country needs.

All of the transitioning countries have experienced a certain level of turmoil and confusion, clearly an expected result given the tremendous changes that have occurred in their economic systems. Since the initial economic conditions for all of these countries were different, it was expected that the progress achieved in each economy would vary as well. For example, the privatization of state-owned property was a larger issue in Czechoslovakia and Hungary where the state owned over 90% of the means of production, including agriculture, in 1989, while much of the farm land in Poland was already privately owned at that time. On the other hand, as early as 1984, Hungary had passed legislation that gave the management of firms some control over state-owned enterprises, effectively positioning firms for privatization before 1989. Nearly eight years later, the transfer process is still ongoing, with varying degrees of success.

One of the most important links in the transition chain is the development of the financial sector. Instead of being mandated to collect and distribute funds according to a central plan, banks and other financial institutions offer a variety of savings opportunities and provide for an efficient allocation of funds. The establishment of banking and capital markets is at the core of the entire financial market plan and is crucial to the development of the private sector.

This book directs attention to the banking and capital market restructuring that was essential to the progress made in transitioning economies. It focuses on the economic progress of four selected countries: Poland, Hungary, The Czech Republic and The Slovak Republic. Not only does their proximity bring them together, but they have a long, established economic relationship. Trade with each other was promoted through the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) and through trade arrangements in the Central European Free Trade Area (CEFTA). They were the dominant economies in the Visegrad group of countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and they are the countries judged by many economists to be most likely to succeed in the transitioning process. Most of them likely will be among the next group of countries admitted to the European Union. While no longer a separate nation, the former East German economy is also included due to its proximity to these countries and its unique experience in the transition process.

While the book is divided into separate chapters by contributing authors, the chapters are grouped by country. Thus, the next three chapters regard the Polish experience, followed by three chapters on the Hungarian transitioning process, four chapters total on the Czech and Slovak Republics, and finally the chapter on the former East German experience. For each country, the articles include (1) information on the macroeconomic development since 1989, (2) a view of the restructuring process in the banking and financial markets, and (3) an analysis of monetary policy and of the central bank in the restructured system. There is also information regarding privatization issues and stock market development.

Regarding the macroeconomic changes, the papers by Polanski, Frait and Tamarappoo, and Vorst, though also to some extent the papers by Wagner and Kominkova and Muckova, provide an up-to-date analysis of basic economic changes. There is detailed information regarding real GDP growth, inflation, and unemployment. In most cases, there also is data regarding exchange rates, the balance of payments and the government budget.

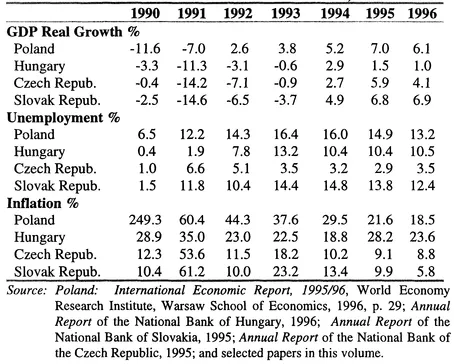

Economic progress is evaluated most often through an analysis of changes in real Gross Domestic Product, inflation and the unemployment rate. While these data do not tell the whole story and may in fact be biased to some degree, the information we have summarized in Table 1.1 below gives an unrefined baseline of comparison for our selected group of transitioning countries. It is important to stress that the data are greatly influenced by the different initial economic conditions, the progress of legislative changes that were so necessary in setting the ground rules, and the variety of programs and methods used in each country in setting up a market structure.

From Table 1.1 it is clear that all of the countries listed made significant economic progress from 1990. Most countries experienced negative growth rates through 1993, after which they were positive for all. It is important to note that the effect of a series of negative rates is cumulative and that it would take several years of positive rates in order to raise the standard of living of individuals in these countries.

Table 1.1 Basic Economic Data for Selected Countries, 1990-1996

The negative growth rates and the ongoing struggle for economic expansion is reflected in the unemployment rate as well. The influence of the state as a large employer is still evident in all countries in 1990. As the transition got underway and the state no longer guaranteed employment, the number of people out of work increased. The unemployment rate also is affected greatly by the "speed" of transition. For example, Poland's "shock therapy" approached resulted in relatively higher rates, compared to the Czech Republic's more gradual approach with lower unemployment. It is difficult to say which method works better. The "shock therapy" approach may result in a critical mass of unemployment that eventually could undermine the transition process. Given the consistent commitment of the Polish government to a market system, this has not happened in Poland to any significant degree. On the other hand, the "gradual" approach allows more moderate adjustment without significant unemployment. However, critics of this approach believe that the unemployment problems are simply delayed and that the country eventually will have to face them. Preliminary information for 1997 (not shown on the table) for the Czech Republic indicate slower growth and higher unemployment.

All of the countries listed in Table 1.1 have experienced significant inflation rates during the 1990-1996 time period. As governments relinquished price controls and liberated prices, inflation resulted, especially in 1990 and 1991. It is a continuing problem in each country but progress is being made. While Poland and Hungary continue to experience double-digit rates, the rates in all countries have shown a downward trend.

The papers by Pulawski and Rapacki, Rutkowska, Botos, Hake, Wagner, and Kominkova and Muckova address the major financial market restructuring issues in each of their respective countries. Information is given regarding the changing structure of the banking market, the bad debt problems of banks and their resolution, the number of banks and foreign capital participation. Some of the articles also provide information on capital market development, specifically with regard to stock exchanges, capital mobility and investment funds.

The few banks that existed in these economies before 1989 took their direction from the state. They acted as repositories for savings and extended credit without financial and economic assessment. This lack of efficient allocation of credit led to substantial loan losses, losses that produced problems for each country's banking system and necessitated creative solutions. The bad loan problem and its solution are described for each of the selected countries in this study.

Most banking systems were modeled after the German model of universal banks. The number of banks and branches expanded in each country with the help of (1) the legislative changes that promoted the expansion of the banking system, (2) the re-education of the public with regard to the financial services available, thereby attracting funds into the system, (3) foreign capital that provided assistance to existing banks, and (4) the entry of foreign branch banks. While the number of private banks has increased, consequently decreasing the state's share of ownership, the state has retained at least partial ownership of banks in each of the countries in this study.

Finally, monetary policy issues during the transition are detailed for each country in papers by Polanksi, Voros, Frait and Tamarappoo, Janackova, Wagner, and Kominkova and Muckova. Under the Soviet scheme, a mono-bank system existed that carried out the funding decisions of the government. A few smaller banks existed but were of little importance and had few duties. The 'central bank' regulated the payments system and provided the funds for the government budget. There was no monetary policy.

In the transition process, countries set up a two-tier system headed by a central bank that was designed to be 'independent' of the government and a regulator of banks in the system. The central bank would now devise monetary policy, regulate the money supply and interest rates, and focus on exchange rate stability. It would determine the necessary changes in its policy tools and in banking regulations. These issues, as well as the problems associated with maintaining independent status, are analyzed in the various studies in this volume.

![]()

2 Polish Monetary Policy in the 1990s: A Bird’s Eye View1

ZBIGNIEW POLANSKI

Introduction

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Polish government launched a stabilization program that marked the initiation of new economic policies. One of the most important components of this stabilization package concerned Central Bank monetary management. In 1990 the National Bank of Poland (NBP) began to conduct an anti-inflationary policy that enhanced the development of market mechanisms. Essentially, this policy is still being pursued by the NBP, although it evolved over time mainly as a result of the development of the financial system and the appearance of new economic problems.

This paper provides an overview of monetary policy in Poland in the 1990s. In the next section, a brief account is given of the macroeconomic development in Poland thus far in the 1990s. The third section outlines the main features of monetary policy with respect to price stability, the money supply, interest rates, currency convertibility, and exchange rates. In the fourth section, specific monetary policy issues such as credit expansion, government debt, bank loan problems, and foreign asset flows are discussed. Conclusions regarding important monetary policy decisions are given in the final section.

Macroeconomic Developments Since 1990

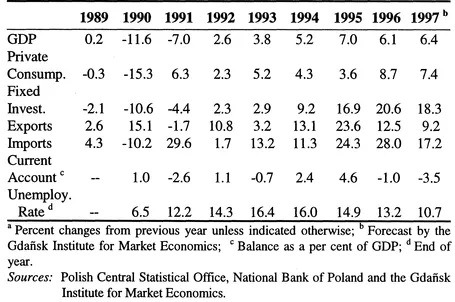

As will be shown, the tendencies visible in Tables 2.1-2.3 did not result from central bank policies alone. Table 2.1 shows that the Polish economy witnessed an economic revival, after an initial economic contraction (1990-1991), mainly due to the stabilization program and the disintegration of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). In 1994 through 1997, Poland's economy was among the fastest growing in Europe.

Table 2.1 Poland's Economic Performance, 1989-1997a

If it were not for the still high unemployment rate, the deterioration of foreign trade and current account balances since 1996, developments in the real economy could be described as a success story. However, our evaluation is not so straight-forward if we take into account the developments in the monetary area.

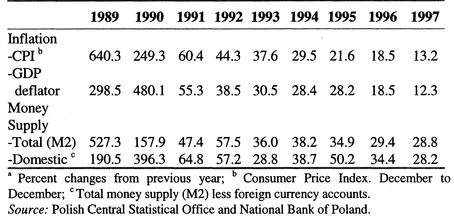

As can be seen in Table 2.2, the inflation rate in Poland is still high and money supply growth is high, although the latter also results from increases in real money demand.

Poland entered the present decade with very strong inflationary pressures, bordering on hyperinflation. The 1990 program clearly reduced the inflation rate. Despite the continuation of stabilization policies, there are serious problems with reducing inflation below 10 percent. Inflation has been strong for more than twenty years and is thus deeply ingrained into the Polish society. Furthermore, many government actions, like administrative price rises or policies aimed at the protection of the agricultural sector, were additionally fueling inflation.

Table 2.2 Inflation and Money Supply in Poland, 1989-1997a

Table 2.3 Structure of the Money Supply in Poland at the end of 1989 and in 1997 (in percent)

|

| Money Supply | 1989 | 1997 |

|

| Total Money Supply (M2) | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Zloty Money Supply | 27.5 | 82.4 |

| Cash in Circulation a | 10.3 | 15.5 |

| Zloty deposits of the non-financial sector | 17.2 | 67.0 |

| Households | 9.0 | 45.9 |

| Business | 8.2 | 21.1 |

| Foreign currency deposits of non-financial sector | 72.5 b | 17.6 |

| Households | 48.8 | 14.3 |

| Business | 23.7 | 3.2 |

|