![]()

Chapter 1

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ULTRASONIC IMAGING

Branko Breyer and Željko Andreić

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter we shall describe basic physical and technological principles of ultrasound diagnostic equipment without extensive mathematical treatment, except for some simple and useful formulas. These formulas are usually supported by worked examples and comments relevant for practical use. Ultrasound diagnostic instruments and procedures are developing rapidly, so that mere knowledge of manipulation with the existing instruments is definitely insufficient for sound usage of the instruments to come. On the other hand, the knowledge of underlying physical principles allows one to understand what is actually new in an instrument, what the supposed advantages are, and how they can be exploited in practical work.

PHYSICAL PRINCIPLES

BASIC CONCEPTS OF WAVES AND SOUND

Sound is mechanical vibration which spreads from its source into the surrounding medium. Such spreading mechanical vibrations are called waves, mostly because in many ways they resemble waves on the water surface. For instance, if we disturb calm water, say, with a wooden stick which we move up and down, water waves will form and spread radially away from the stick. In an analogous way, sound waves are produced by disturbing the air somehow, and they spread in all directions away from their source. When we speak about sound waves, we intuitively think about audible sound which we can hear and which spreads in air. Sound waves can also exist in other media and can be totally imperceptible to us. What is common to all “sound” waves is that they can be described by the same laws of nature.

The vibrating object which produces the sound is called the source. This source is somehow made to vibrate, and its vibrations disturb the medium around it. The produced disturbances spread away through the medium around the source in the same way the water waves spread around the moving stick. If we look at the water waves more carefully, we will see that the water itself does not flow. It just moves up and down, and the movements travel from the stick outwards. This can be verified by a simple experiment. If we put a few small chips of wood on the water surface and watch their movements as the wave passes by, we can see the chips moving up and down while the wave is passing by them, but after the wave is gone, they are again at rest at their original positions. So, only the disturbance travels through the water, while water itself stays at rest. This traveling disturbance is called a wave, and under normal circumstances it produces no flow of medium through which it spreads. In audible sound waves, air molecules are moved back and forth around their positions in the direction of wave spreading. Such a wave is called a longitudinal wave. All sound waves in normal circumstances are longitudinal. In some cases, transversal waves or waves with complicated particle motions can exist, but we shall limit our discussion only to the longitudinal sound waves because only such waves are used for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

TABLE 1

Speed of Sound and Characteristic Acoustic Impedances of Some Materials

Medium | Speed of sound (m/s) | Characteristic acoustic impedance (106 kg m−2s−1) |

Air 20°C | 340 | 0.000411 |

Water 20°C | 1480 | 1.5 |

Castor oil | 1540 | 1.46 |

Perspex | 2680 | 3.17 |

Steel | 5950 | 46.6 |

Pyrex® glass | 5610 | 13 |

The speed with which the wave travels through the medium is called the speed of sound (in that medium). The number of oscillations the wave makes in 1 s is called the frequency of the wave. In our water wave experiment, we can measure the speed of the wave by measuring the time it needs to travel some known distance, between two wooden chips for instance. We can also measure its frequency by counting how many times a particular chip has been moved up and down in 1 s. In a similar manner, we use measuring instruments to measure the speed and frequency of sound in air, water, or other media.

The human ear can hear sound waves with frequencies from about 16 to about 20,000 Hz. The Hertz (Hz) is the unit of frequency; 1 Hz means one full oscillation in 1 s. Larger units used are kilohertz (kHz), 1 kHz = 1000 Hz, and megahertz (MHz), 1 MHz = 1 million Hz = 1000 kHz.

Sound with frequency in the range 16 Hz to 20 kHz is usually called audible sound, and the 16-Hz to 20-kHz frequency span, the audible range. For illustration we can mention that musical tone AO is given by a tuning fork which has the frequency of exactly 400 Hz (Table 1).

If we divide the speed of sound with the frequency of sound, we get the length between the adjacent wave peaks in the traveling wave. This length is called the wavelength of the wave.

| (1) |

or, abbreviated

where λ means wavelength, c is the speed of sound, and f is the frequency of sound.

***

The formula λ = c/f is a very useful one. It can be used to find one of the three basic sound parameters if we know the other two. Usually, diagnostic ultrasound is described with its frequency. The speed of sound in soft tissues is known to be about 1540 m/s, so we can use this knowledge to find the wavelength of the ultrasound wave. For instance, if we use a probe which generates 2 MHz ultrasound waves, their wavelength in soft tissues will be

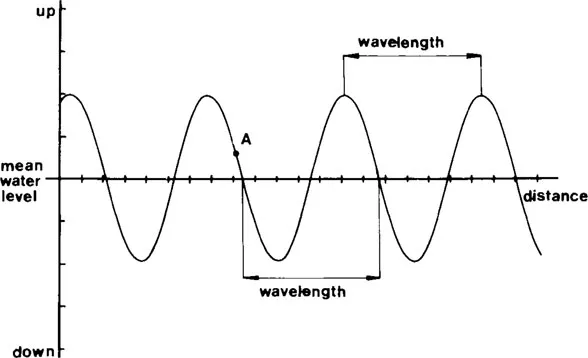

FIGURE 1. A cut-through of water surface disturbed by a simple water wave shows a characteristic sinusoidal pattern of raised and lowered parts of the surface. The image is frozen in time. In reality, this pattern moves outwards from the wave source with constant speed. Distance between two adjacent wave peaks (or valleys) is called wavelength of the wave.

We can also rearrange the formula to find other two parameters:

or simply

***

Suppose that we somehow freeze the water in one moment during the water wave experiment and make a cut through the frozen water surface. We shall get the water wave profile in that moment, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

As this simple picture illustrates, water surface is somewhere raised and somewhere lowered in a sinusoidal pattern. The wavelength is the distance between two adjacent maxima (or minima). The SI unit for wavelength is meter (m), with subunits of cm (1 cm = 0.01 m), mm (1 mm = 0.001 m) and μm (1 μm = 0.001 mm). The speed with which this profile moves away from the source is called the speed of sound (in a particular medium, in our case, water). This speed is constant for homogeneous media and is measured in meters per second.

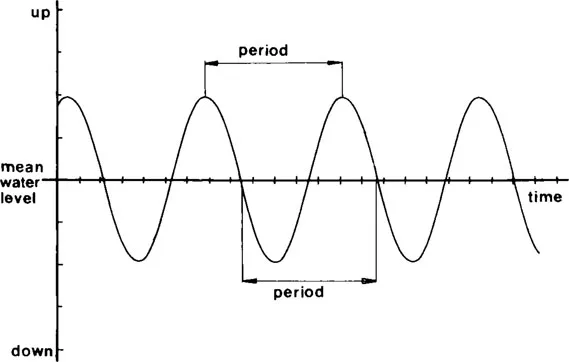

FIGURE 2. Vertical position of a stationary point on the water surface disturbed by a simple wave varies sinusoidally with time. Period of the wave is defined as time needed for one complete oscillation.

Imagine now that we stay at some stationary point on the surface (on one of our wooden chips, for instance) and observe the motions of the surface at that point as the wave is passing by. We shall get a picture very similar to the previous one (Figure 2).

Please note that the value plotted on the abscissa (x-axis) of this graph is time, not distance. While the first graph illustrates wave behavior in space, the second illustrates wave behavior in time. Now, the amount of time between two adjacent wave maxima (in time) is called the period of the wave. As we have said before, the frequency of the wave is the number of oscillations in 1 s, so it is obvious that

| (2) |

| (2a) |

***

Sound is mechanical vibration which travels through the medium. It is produced by vibrating objects. A sound wave is described with its frequency, or its wavelength, and its amplitude. The speed of sound in a homogeneous medium is constant and the basic relation is

***

SOUND PRESSURE AND ENERGY

So far, we have said that a sound wave is a disturbance which travels through some medium. As the source vibrates, it pushes and pulls particles of the surrounding medium. In other words, it exerts some force on the particles. When we describe such a force, we usually talk about force per unit area, the pressure.

***

The SI unit of force is Newton (N). 1 N is the force which in 1 s can accelerate a body of 1 kg mass to the velocity of 1 m/s. When we speak about forces in gases and liquids, we usually talk in terms of pressure. Pressure is the force acting on a unit area perpendicular to the direction of the force. The SI unit for pressure is Pascal (Pa). 1 Pa means the force of 1 N distributed over an area of 1 m2. For illustration: mean atmospheric pressure at sea level is about 100,000 Pa. Larger units for pressure are often used:

***

The source of sound produces oscillating pressure variations in the surrounding medium. The pressure oscillations travel through the medium as a sound wave. This wave has a certain amount of energy which is carried with the wave. This amount is proportional to the mean squared pressure variation.

We can describe a sound wave in many ways. We can describe it as a traveling disturbance of the medium or as a traveling pressure wave, etc. All these descriptions are valid and are used in discussions of sound characteristics and effects. Usually, a description which suits the particular problem best is used, although different authors have different definitions for “most suitable”. However, for us, it is important to remember that many descriptions are possible. From now on, we shall...