eBook - ePub

Early Warning Indicators of Corporate Failure

A Critical Review of Previous Research and Further Empirical Evidence

- 425 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Early Warning Indicators of Corporate Failure

A Critical Review of Previous Research and Further Empirical Evidence

About this book

Published in 1997, this text focuses on the conundrum between the academics ability to distinguish between failing and non-failing businesses with models of over 85.5per cent accuracy, and the reasons why credit agencies and the like do not act on such information. The author asks, are the models defective?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Early Warning Indicators of Corporate Failure by Richard Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The background

Introduction

The argument

Finding ways of trying to identify failing companies as early as possible is clearly a matter of considerable significance to businessmen and other interested parties. For instance, if an investor or creditor is able to predict a company on the path to bankruptcy before anyone else, he or she will be able to liquidate the investment or obtain settlement of a debt and so minimise losses. Similarly, it is vitally important for an auditor in preparing his or her report to be able to assess whether or not a company is a going concern.

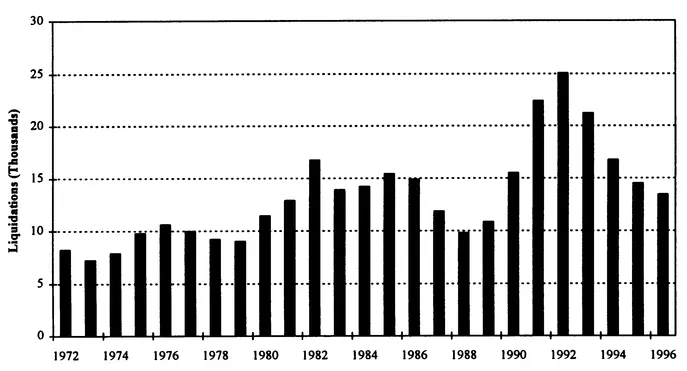

In fact, the rate of failure amongst new small businesses has always been high, upwards of a third of newly established companies collapsing within five years of incorporation.1 By contrast, the rate of failure amongst listed companies is much lower, the attrition rate being rather less than 2 per cent per annum. Nevertheless, it is a matter of some concern that the number of bankruptcies, both of listed and unlisted companies, has increased in recent years as the British economy has suffered a series of destabilising shocks (see Figure 1.1). Moreover, it is noticeable that over time financial distress appears to be experienced in different industry sectors.2

Against this background there has inevitably been a growing urgency on the part of investors, bankers, trade creditors, company directors and auditors to try to find better ways of trying to identify firms likely to go bankrupt,3 a demand which researchers have sought to satisfy by developing a number pf different procedures which aim to give early warning of financial distress.4 But for a variety of reasons (see p. 27) this research has overwhelmingly concentrated on predicting the fate of listed companies rather than their far more numerous unquoted counterparts, where however the risk of failure is far greater.

Figure 1.1 Company liquidations5

Source: Annual Abstracts of Statistics

Source: Annual Abstracts of Statistics

What is puzzling is that if there is a well established method of identifying failing listed companies in advance of their final collapse, one might reasonably expect investors and creditors to use the procedure and immediately act upon its predictions. Consequently, as soon as a new and accurate forecasting approach has been established, one would expect it to be universally adopted. The result should be that listed companies forecast as very likely to go bankrupt ought to fail immediately.

In the circumstances it is therefore a little perplexing that many experts in the field seem to claim that they can successfully predict with remarkable accuracy which listed companies are very likely to fail and which are not.6 Indeed, it is not unusual to find that success rates of over 90 per cent are claimed, not just immediately a new prediction model has been derived, but consistently thereafter when the diagnostic procedure has been well publicised, which stretches credulity to the limit.

Of course, investors and creditors, and the agents who work on their behalf, will search endlessly for a novel procedure that might give them a narrow (and presumably short-lived) advantage. If successful, analysts and their clients stand to make a lot of money - or, at least, in the case of the latter, not to lose heavily! It is therefore quite easy to believe that each innovation which improves the accuracy of predictions will be well worthwhile. But what is more difficult to accept is that a new approach will continue to be successful in terms of earning abnormal risk-adjusted returns after its existence becomes known and analysts are able to mimic its forecasts. Its prophecies should then become self-fulfilling. In fact, the argument and evidence presented in this book appear to provide an answer to the conundrum. Basically the 'prediction' models, however derived, seem to come up with a very similar (and unsurprising) answer: namely, that immediately prior to bankruptcy, the accounts of failing listed companies show high levels of borrowing and low profitability. The problem is that, outside the sample period and/or when allowance is made for sample selection bias, a relatively high proportion of non-failing listed companies - some 20 per cent are also identified as prima facie failures.

Effectively this seems to imply that in any one year a UK analyst referring to one of the models that have been developed would correctly identify the dozen or so listed industrial companies which will go bankrupt within 12 months, but will incorrectly classify around 120 of the remaining 600 as likely to fail. Clearly analysts who might refer to the models to assist them in managing their portfolios are likely to try them out before relying on them blindly and thus make them self-fulfilling. It seems improbable, in fact, that a misclassification error rate of 20 per cent for non-failing listed companies would be regarded as acceptable, even allowing for the significantly higher costs of incorrectly identifying a failing company as sound when compared to those of misclassifying a non-failing company as prima facie bankrupt.7

Consequently it would seem that, where analysts refer to the models, they do so primarily as a shorthand procedure for summarising data about a company. Given the diversity of the businesses from which the underlying financial ratio data are derived, it appears that the classifications really just reflect the fact that listed companies reporting losses or low profits and which are burdened with debt are more at risk than otherwise similar companies which are recording reasonable profit figures and which have lower gearing ratios. But the plight of a financially distressed company should be fairly obvious anyway, and it would not be unreasonable to expect relative share prices to reflect the outward condition of a business, regardless of whether it eventually fails or not. Interestingly, the evidence reported later in this book seems to support this argument.

The implication therefore seems to be that there are few, if any, unambiguous early warning signals of impending bankruptcy. On the other hand, there is a significant proportion of listed companies - around a fifth, perhaps - which in any one year might be regarded as 'at risk', but the vast majority of which are turned round and/or do not fail.

Some basic issues

It is against this background that various basic issues will be reviewed in this chapter. This will set the scene for the argument and review of the evidence which follows.

In particular, it is first necessary to identify what exactly is meant by the term 'failure'. At one extreme it can obviously mean liquidation; but at the other it could just mean reporting a profit figure below that expected. In between are various possible definitions of what precisely is meant by the term.

It is also appropriate to consider what is meant by 'prediction'. In fact, it can mean being able to discriminate after an event or before an event - although it is only the latter which is really of interest to a decision maker.

In addition, there are a number of other fundamental methodological issues which need to be considered. For instance, before engaging in empirical research it is highly desirable to try to establish by deductive reasoning what factors might reasonably be expected to bring about the failure of a business. Such theories are known as 'normative theories'. By contrast, it is possible to develop 'positive theories' (explaining what is rather than what ought to be) through empirical observation.

In fact, most of the research into corporate bankruptcy seems to be driven by empirical evidence, and it is therefore appropriate to try to identify potential difficulties in developing research designs which might bias the results in a particular direction. One obvious distorting factor is the matched pairing technique generally adopted, when the annual incidence of failure is far less than 50 per cent of a population of companies in a given year. Interestingly there are ways this can be allowed for, and when suitable adjustments are made it appears that the discriminatory power of so called prediction models is substantially reduced. Another problem concerns the way in which the accuracy of predictions is calculated, either pairwise or across complete samples of failed and non-failed companies.

It is also necessary at the outset to say something briefly about informational market efficiency and various 'user needs'. In the case of the former, the argument presented above suggesting that a successful prediction procedure should immediately be applied by analysts implies informational market efficiency. Brief reference will therefore be made to the very substantial body of empirical evidence which suggests that, after allowance is made for search costs and rewarding special skills, financial markets do appear to be very close to being informationally efficient.8

As for user needs, it is also appropriate to focus more closely on what might be of interest to investors, creditors, company directors, auditors and other third parties. In particular, it may well be that some investors or creditors will be prepared to put their money into specific high risk companies, knowing that some will fail but that overall the rewards will more than offset the losses they will make on some of the investments or loans in their portfolios.

As for directors and auditors, they have always had to decide whether or not a company is a 'going concern', since that will determine whether a company's accounts will be approved by the board and the nature of the audit certificate attached to them. However, recent changes in legislation affecting the rights and duties of directors, as well as to rules concerning the audit of company accounts, have focused attention more closely on the matter. It is therefore necessary to consider the significance for both directors and auditors of being able to assess the likelihood of a company failing in the foreseeable future.

The meaning of ‘failure’

'Corporate failure' fairly obviously encompasses 'bankruptcy', which for a company effectively means a creditors' liquidation or the appointment of a receiver. However, the net can be drawn more widely to embrace situations where there is evidence of 'financial distress'. It may therefore be useful to list a spectrum of potential indicators of such distress, beginning with situations where there is general agreement on what constitutes failure and working down to other circumstances which are more indicative of a company's possible financial difficulties, e.g.

- (1) creditors' or voluntary liquidation, appointment of a receiver;

- (2) suspension of Stock Exchange listing;

- (3) going concern qualification by the auditors;9

- (4) composition with the creditors;

- (5) protection sought from creditors (e.g. under Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code);

- (6) breach of debt covenants, fall in bond or credit rating, new charges taken over the assets of the company or its directors;

- (7) company reconstruction;

- (8) resignation of directors, appointment of a company doctor, etc;

- (9) take-over (although not all take-overs are witness to financial distress, of course);

- (10) closure or sale of part of the business;

- (11) a cut in dividends or the reporting of losses; or

- (12) the reporting of profits below a forecast or acceptable level; and/or the fall in a company's relative share price.

Generally corporate failure studies concentrate on the first few items in the above list, although some of the others may be taken as indicators of impending difficulties. There is also an extensive literature on changes in corporate bond and credit ratings10 and on corporate turnarounds.11

The meaning of ‘prediction’

Many studies on corporate failure specifically refer to predicting bankruptcy. It is therefore necessary to deal with another semantic issue which is all too rarely addressed in the literature - namely, what exactly is meant by 'prediction'.

In fact, 'prediction' has two distinct meanings, and it is important to distinguish between them.

- (1) Prediction can mean 'identification' - i.e. in a narrow statistical sense it should be possible historically (or 'ex post') for a given population of companies to predict (identify) which businesses went bankrupt and which did not. Such an autopsy can be useful as a way of enhancing understanding of the phenomena which characterise corporate failure.

- (2) Prediction can mean 'forecast' - i.e. it implies that it should somehow be possible to distinguish in advance (or 'ex ante') those firms which, within a given time span, will fail and those which will not.

For decision makers it is essentially the second of these which is of interest, especially if there is a procedure which would enable them to increase returns (reduce losses) on their investment portfolios. However, in a highly competitive market analysts would be expected to use any procedure which would enable them to distinguish between 'winners' and 'losers'. In other words, just as in betting markets, it is difficult to conceive of an 'unfair game' situation existing for any length of time. Consequently, although it is possible that a new innovatory form of analysis might give its creator a momentary adv...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Executive summary

- 1 The background

- PART I: Previous research

- PART II: The empirical studies

- Appendix: Sample and control companies

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Subject index