The Classification of Offences

The most important basic distinction to be made within the range of criminal acts is between offences against the person and those against property. The former will include the homicide group (murder, manslaughter, infanticide); assaults and woundings; sexual offences; and robbery. Property offences comprise various kinds of theft; trust offences such as fraud and embezzlement; criminal damage; and arson. A third category is less easily defined in strictly criminal terms – so-called social disorganisation offences including drunkenness, drug-taking and prostitution. Although this third group properly demands examination of its environmental correlates, data difficulties are quite severe, and the discussion will focus primarily on personal and property offences. These distinctions are complicated in Britain by the method of prosecuting offenders. The 1977 Criminal Law Act redefined modes of trial: offences labelled ‘serious’ in British criminal statistics refer to those which are tried (1) only on indictment at a Crown Court or (2) either on indictment or summarily at a magistrates’ court at the discretion of the defendant. The scope of ‘serious’ offences differs slightly from the previous ‘indictable’ category (see Home Office, 1980, sections 1.17 and 1.18), but the terms will be used interchangeably in this volume. Most property offences are in the ‘serious’ category but a large number of minor assaults remain in the ‘summary’ category. Similar definitional problems exist in the United States with the FBI statistics.

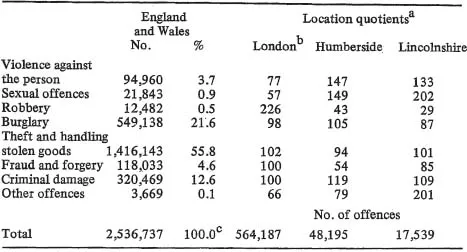

Table 1.1 gives the breakdown of serious offences for England and Wales in 1979. The predominance of property offences is abundantly clear – over 95 per cent of the total. In terms of numbers, offences against the person are much rarer (about 5 per cent). In order to highlight right away some of the considerable variation which exists in the incidence of different types of offending, location quotients are calculated for three contrasting police authorities. The Metropolitan Police is by far the largest police force in Britain — some 22 per cent of serious crime in England and Wales occurs within its jurisdiction. Robbery is the offence which is relatively most prevalent in London. Sexual offences and violence are well below the national proportion.

Humberside is a medium-sized county, fairly urbanised but without a large conurbation. It stands in marked contrast to London, with a high proportionate incidence of personal violence and sexual offences and lower than average rates for robbery and fraud. The patterns for Lincolnshire, a largely rural police area, present yet further contrasts. While sexual offences occupy a higher proportion than in either of the more urbanised areas, personal violence is not so exaggerated as in Humberside. As might be expected, robbery is least likely in the rural context although, curiously, criminal damage is relatively more prevalent. Burglary is less common in Lincolnshire but otherwise it and theft show little tendency to be differentiated between police areas.

Table 1.1: Serious Offences Recorded as Known to the Police: England and Wales,1979

a. Location quotients measure the concentration of serious offences relative to the national average. An area with exactly the national average proportion of offences in a category would have an LQ of 100 for that category. The higher the LQ, the greater the proportionate incidence of that offence type.

b. Metropolitan Police District and City of London.

c. Percentage cohunn does not add up due to rounding.

Source: Home Office (1980), Table 32; LQ calculations by author.

The lesson to be learnt from these figures is that any breakdown of the crime rates, either by areas or by types of crime, instantly reveals considerable and conflicting disparities. And this is only within officially recorded crime: true crime rates may be of the order of two to ten times higher. Moreover, the relationship between true and official crime is itself subject to wide variation. In America, victimisation surveys have found (Table 1.2) that only 27 per cent of rape incidents get reported and the proportion of burglaries notified to the police is little higher. At the other extreme, for homicide and vehicle theft, reported crime actually exceeds estimates of the true incidence (homicide victims don’t normally have the opportunity of reporting their experience; insurance considerations motivate reporting vehicle theft). Overall rather less than half of serious crime in the United States is reported. In a survey of London, Sparks et al. (1977) suggest that less than one-third of criminal victimisations are notified to the police. From the official rate we cannot tell whether the high proportion of sexual offences in Lincolnshire is because that county is a hotbed of sexual deviation or because such offences are much more likely to be reported in tightknit rural and small town communities.

Table 1.2: Relations Between Real and Official Crime Rates: United States, 1965–6

| | Rates per 100,000 population | Official as per cent of real |

| Crime type | | | |

| | Reala | Officialb | |

| Homicide | 3.0 | 5.1 | 170 |

| Forcible rape | 42.5 | 11.6 | 27 |

| Robbery | 94.0 | 61.4 | 65 |

| Aggravated assault | 218.3 | 106.6 | 49 |

| Burglary | 949.1 | 296.6 | 31 |

| Larceny (over $50) | 606.5 | 267.4 | 44 |

| Vehicle theft | 206.2 | 226.0 | 110 |

| All Part I Crimes | 2119.6 | 974.7 | 46 |

a. Estimated from national victimisation survey.

b. Uniform crime reports adjusted to exclude non-residential burglary and larceny.

Source: Ennis (1967).

Gross Offence Rate

International comparisons of gross offence rates are almost impossible because of differences in the scope and coverage of legal and judicial systems. At various sub-national spatial scales, however, the gross rate provides an introduction to the discussion of particular crimes. Even so we should be wise not to expect too much from the gross offence rate – it can, as we shall see, be quite misleading.

(a) Regional Variations

Regional variations in overall crime rates can be considerable. Harries (1971), in a study of the United States, shows that the rate varies from 634 offences per 100,000 population (North Dakota) to 3,764 (California). In general, crime rates are highest in the most urbanised regions (Northeast, Midwest and Pacific coast) and lowest in the rural Mountain, Great Plains and Southern states (see Figure 1.1). In Britain regional variations are less exaggerated but nevertheless are still clear (Figure 1.2). However, most commentators on this level of analysis take pains to point out that, with the exception of violence, the real relationship is between crime and urbanisation and that regional variations coincidentally reflect differences between regions in the size and importance of urban agglomerations.

Figure 1.1: Regional Variation in Gross Crime ...