eBook - ePub

Introduction to Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy

About this book

1997 was the 'Year of the Electron' because it marked the centenary pf the celebrated discovery of the smallest of the fundamental particles that make up ordinary matter, and which has proved to have so many remarkable properties that, after light, it has become the most widley used of the particles in scientific and technogical applications. STEM is a discipline of importance to a growing number of microscopists. This book is essential reading for undergraduates, postgraduates and researchers requiring an up-to-date and comprehensive introduction to this rapidly growing, state of the art technique.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introduction to Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy by Dr Robert Keyse,Anthony J. Garratt-Reed,P.J. Goodhew,Prof Gordon Lorimer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Why STEM?—STEM versus TEM

1.1 Introduction

What is STEM? The acronym literally means scanning transmission electron microscopy (or microscope) and implies transmission electron microscopy (TEM) performed with a scanned, focused electron beam. Since conventional TEMs have been available for about 40 years and have been developed to a state at which they have an extensive range of capabilities, we need to answer the question ‘why bother with STEM?’. We aim to answer this question in this first chapter, before going on to describe the operation and some of the theory of the STEM in later chapters.

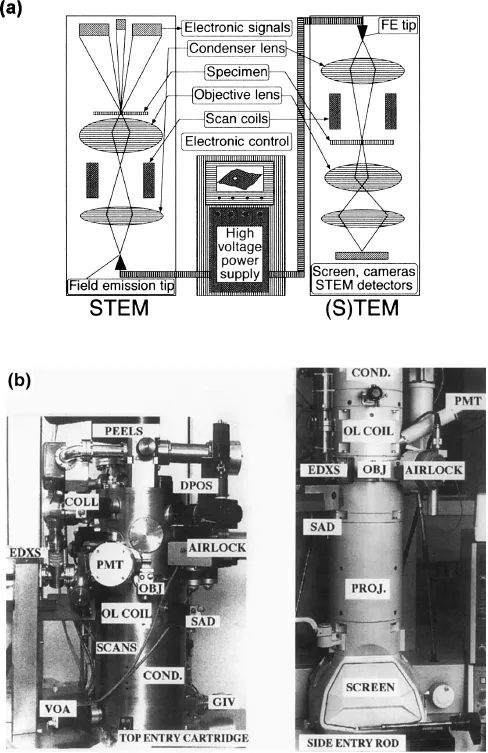

In principle, STEM is a very straightforward technique, as Figure 1.1 shows: a fine electron probe is scanned across a thin specimen and the intensity of the transmitted electron signal is measured using one or more electron detectors. An image is thus built up point by point, just as in a television or a conventional scanning electron microscope (SEM). If other detectors such as an X-ray detector or an electron energy-loss spectrometer are attached then chemical microanalysis can be performed point by point. If a secondary electron detector is incorporated then an SEM image can also be obtained.

You might argue that all this can be done either in a conventional SEM or in a conventional TEM modified to allow scanning of the beam. The essential difference between these conventional microscopes and a true STEM instrument lies in the (small) size of the probing electron beam and the current density (electrons per second per unit area) it can deliver to the specimen.

A TEM may have a thermionic electron source with a tungsten or lanthanum hexaboride (LaB6) emitter, or a field emission (FE) source. A TEM with the appropriate detectors, scanning coils, and any of these sources can act as a STEM. However, the technique comes into its own when used with a high brightness FE source because only then can a very fine probe (less than 1 nm in diameter) be used to deliver a high current (more than 0.5 nA, or about 1010 electrons per second). If chemical analysis or diffraction is to be carried out with the fine probing beam stationary for many seconds on a single part of the specimen, then a clean specimen and a clean high vacuum environment are essential, or the part of the specimen being examined will rapidly be contaminated. When a FE source is combined with an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) scanning transmission electron microscope column the instrument is usually known as a ‘dedicated’ STEM.

STEM instruments tend to cost more than TEM instruments because there are UHV requirements, additional components in the microscope, and extra electronics to drive them. One advantage of STEM is the ease of interfacing to a computer, since by its very nature a STEM is an electronic microscope. High direct magnification TEM images are sometimes only dimly visible on the phosphor screen and they often have only limited contrast; in STEM the image stays bright even at the highest magnifications and contrast can be adjusted electronically. It is usual to conduct TEM experiments in a darkened room (so your eyes become dark adapted), but with a STEM one normally only dims the lights for comfort. A lot of the guesswork is taken out of STEM investigations, for example when focused at high magnification the image remains focused at any lower magnification. Also, since only those parts of the specimen that are scanned are irradiated, there is no hidden beam damage occurring outside the field of view. At first sight STEM may appear to be a complicated and sophisticated technique, but times are changing and ease of use has become a major design goal.

It may be useful at this point to clarify some of the acronyms which are used in discussing this area of microscopy. We give some of the most common in Table 1.1.

Although both TEM and STEM instruments produce transmission electron images there are a number of very significant differences between the imaging modes. Let us consider four of these differences immediately.

Table 1.1. Some commonly used acronyms

| Acronym | Meaning |

|---|---|

| AEM | Analytical electron microscope (implicitly an analytical TEM) |

| CTEM | Conventional TEM |

| EDXS | Energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (often EDX or EDS) |

| EELS | Electron energy-loss spectrometer (or Spectroscopy) |

| FEG-STEM | Field emission gun STEM |

| HREM | High resolution electron microscopy (usually in a CTEM) |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| STEM | SEM with transmission facility (usually a dedicated STEM) |

| (S)TEM | TEM with scanning facility (STEM in a conventional TEM) |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscope |

1.2 Image formation

A conventional TEM (CTEM) produces a parallel image on a screen, photographic plate, or camera, in which all pixels are recorded or observed simultaneously and the image magnification is controlled by the projector lenses after the beam has passed through the specimen. In a STEM the image is collected in series, pixel by pixel, and no lenses are required for image magnification. In principle this helps to preserve a high quality image in STEM because aberrations in ‘post-specimen’ lenses do not influence the image quality. However, in practice the STEM probe-forming lens aberrations prove to be a limitation and the ultimate performance of a STEM is usually aberration-limited just like a TEM. Providing the aberrations are limited the ultimate beam diameter can be made very small; it is possible to use a STEM for high resolution electron microscopy (HREM) as shown in Chapter 4 (see Figure 4.8).

1.3 Beam convergence

When a beam of electrons is focused to form a very fine electron probe it is almost inevitable that it will be highly convergent (in the TEM one often converges the beam to a spot at the specimen). Consequently, at all times during STEM image formation and microanalysis the beam is very convergent. In contrast, images are usually obtained with a TEM by using a ‘defocused’ beam of almost-parallel electrons. We will show in Chapter 4 that this affects the way in which we can use a STEM to form diffraction contrast images and it also affects the appearance of diffraction patterns, as we will show in Chapter 5. We shall invoke the principle of reciprocity to explain these effects; that is, that any optical system behaves identically if the direction of the radiation (light or electrons) is reversed.

1.4 Diffraction patterns

The highly convergent probe in a STEM emerges from the far side of the specimen as a convergent beam diffraction pattern. It can be seen from Figure 1.1a that at all times there is only ever a diffraction pattern in the column of a STEM. Consequently, if we stop the beam scanning and record the distribution of electron paths in the column of the microscope, we have recorded the diffraction pattern from a small region of the specimen. Many dedicated STEMs are not designed to do this with the greatest ef...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Introduction to Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- 1. Why STEM?—STEM versus TEM

- 2. STEM optics

- 3. The specimen

- 4. Imaging in the STEM

- 5. Diffraction in the STEM

- 6. Microanalysis in the STEM

- 7. Mapping in the STEM

- 8. Limits to STEM and advanced STEM

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix B: Further reading

- Index