![]()

Part One Introduction

The three chapters of Part I present the basic theoretical background to geomorphic concepts and problems (Chapter 1), an historical perspective of models of landform evolution (Chapter 2) and an introduction to the external and internal processes affecting landform development and erosional evolution (Chapter 3).

![]()

One Approaches to geomorphology

Geomorphology (Greek: ge – ‘earth’, morphe – ‘form’, logos – ‘a discourse’) is the scientific study of the geometric features of the earth’s surface. Although the term is commonly restricted to those landforms that have developed at or above sea level, geomorphology includes all aspects of the interface between the solid earth, the hydrosphere and the atmosphere. Therefore, not only are the landforms of the continents and their margins of concern, but also the morphology of the sea floor. In addition, the close look at the moon, Mars and other planets provided by spacecraft has created an extraterrestrial aspect to geomorphology.

1.1 Concepts

Geomorphic studies comprise a spectrum of approaches between two major, interrelated conceptual bases:

(1) Historical studies which attempt to deduce from the erosional and depositional features of the landscape evidence relating to the sequence of historical events (e.g. tectonic, sea level, climatic) through which it has passed.

(2) Functional studies of reasonably contemporary processes and the behaviour of earth materials which can be directly observed and which help the geomorphologist to understand the maintenance and change of landforms.

Functional studies explain the existence of a landform in terms of the circumstances which surround it and allow it to be produced, sustained, or transformed such that the landform functions in a manner which reflects these circumstances. Historical studies explain the existing landform assemblage as a mixture of effects resulting from the vicissitudes through which it has passed. Thus functional explanation is most applicable to those landforms which most clearly manifest the effects of recent processes to which they have readily responded, whereas historical explanation is reserved most obviously for landforms whose features have evolved slowly and which bear witness to the superimposed effects of climatic and tectonic vicissitudes, i.e. they are a palimpsest (like a surface which has been written on many times after previous inscriptions have been only partially erased; Greek: palin – ‘again’, psegma – ‘rubbed off’). It is clear that most objects of geomorphic interest show evidence of both functional and historical influences and this is one of the reasons why so many geomorphic problems are open to widely differing approaches. Most functional explanation is directed towards prediction, the deducing of effects produced by causative factors (i.e. independent variables); whereas historical explanation rests on retrodiction, the derivation of a chronology of a sequence of past landscape-forming events. Both functional and historical studies require a description of the landform or landscape, either quantitatively or qualitatively. This is the groundwork of research, but description itself rests on one of the conceptual bases which define the rules by which description is carried out.

An understanding of the erosional and depositional processes that fashion the landform, their mechanics and their rates of operation must also be obtained in order that the past evolution can be explained and the future evolution predicted. This ‘process geomorphology’ has a strong utilitarian aspect. The great complexity and diversity of landscape features has led to different approaches to the study of landforms. The engineer is interested in a description of the landform and an assessment of its stability and short-term rate of change, which is of great practical concern. The geologist wants to know how various lithologic units affect the landscape, so that this understanding of geologic control of landforms can be used to map the rocks and structures from aerial photographs or satellite images. Geomorphologists use different approaches and techniques of study depending on their goals which may be description, retrodiction, prediction, or all three.

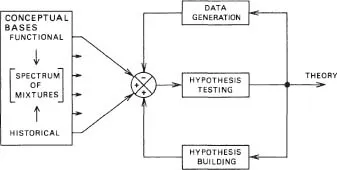

It is commonly believed that scientific investigation proceeds by the method of multiple working hypotheses. Stated in a highly oversimplistic manner, this method is thought to involve the collection of a body of observations, and the formulation of a number of distinct hypotheses which might explain the observations. The next step is the deduction of further possible ‘facts’ which would logically be expected to result from the reality of each hypothesis. Finally, there is the testing of the hypotheses by trying to verify the deduced ‘facts’ by further observation, and the modification and combining of hypotheses to produce the most probable one, which can then be elevated to the rank of theory. Of course, the strict application of this method is not possible because all scientists approach the problems of the real world from conceptual bases the sources of which are difficult to determine, and the effects of which are to set in train complex loops of description, data generation, hypothesis-building and hypothesis-testing (Figure 1.1). Each of the two most important conceptual bases for theory-building in geomorphology, the historical and the functional, prompts a particular type of investigation. It is clear, however, that certain explanations of complex landforms must involve elements of both.

Although there are different approaches to geomorphology and investigations may have very different objectives, nevertheless, there are several concepts that are basic to landform studies. Expressed in four words, these are uniformity, evolution, complexity and systems.

Figure 1.1 The relations between conceptual bases, data generation, hypothesis-building, hypothesis-testing and theory construction. Conceptual bases and hypothesis-building create more ( +) hypotheses for testing, whereas data generation by field observations may decrease (-) the number of viable hypotheses for testing; ( +) and (-) represent positive and negative feedback, respectively.

When present landform evolution and the operation of erosional and depositional processes are understood, the principle of uniformity (i.e. that the present is the key to the past) can be invoked to extend the results into the future (prediction) or into the past (retrodiction). Great care must be exercised in the application of this principle, mainly because of the complexity of landform evolution and the interruption of the evolution by other factors (tectonic, climatic and human). Nevertheless, in its simplest form, uniformity means that basic physical and chemical relationships apply equally to the present, the future and the past. For example, although rates of erosion may be very different, the behaviour of fluids on a slope or in a channel is known and the hydraulic relations can be extrapolated forward and backward in time.

The earth’s surface is dynamic and landforms change through time. This evolution occurs in different ways, at different rates and during variable periods of time. Between 1884 and 1899, in the wake of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859), the American geomorphologist William Morris Davis (1850–1934) developed his cycle of erosion theory for landforms based on the view that, for them, evolution implies an inevitable, continuous and irreversible process of change producing an orderly sequence of transformation stages of landform assemblages from youth through maturity to old age. In this way Davis was using a paradigm (Greek: para – ‘beside’, deiknoomi – ‘to show’); in other words, a model developed in another discipline which appears to possess such general power, pervasion and applicability that it can be usefully employed in geomorphology. Davis’s cycle of erosion concept represented an application of Darwin’s biological paradigm and, in much the same way, the systems approach to geomorphology finds its roots in the thermodynamic paradigm which emerged in the latter half of the last century. Davis thus provided a theoretical model for the cyclic landforms which he would expect to evolve in the period between the initial uplift of a land surface and its subsequent reduction to a surface of low relief (i.e. a peneplain). However, as will be seen later in this chapter, there may be no evidence for such an orderly evolution in the sequence of changes undergone by an assemblage of landforms.

Although during very long spans of time one can conceive a slow progressive evolution towards an increasing uniformity of landforms (i.e. increasing entropy), the details of this change are usually complex with periods of erosion or incision being followed by periods of deposition, as landforms respond to changed conditions (e.g. climate, baselevel, land use). This complexity has been especially marked during the last few million years of earth history which have been characterized by climatic and tectonic change and by the increasing impact of man’s activities. Therefore, landscape evolution may be expected to involve the development of complex landform assemblages (e.g. those developed over long timespans, covering large areas, influenced by many factors, subjected to many threshold effects etc.), the explanation of which employs elements of a wide spectrum of conceptual bases. Thus the dimensions of a river may depend partly on the effects of the mechanics of wa...