![]()

INTRODUCTION

1 Principles and rationale of radiomics and radiogenomics

Sandy Napel

![]()

Principles and rationale of radiomics and radiogenomics

SANDY NAPEL

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Principles and rationale of radiomics and radiogenomics

Acknowledgments

References

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, the radiologist’s job was focused on the interpretation of images, which, until recently, was facilitated entirely by their observations and supported by their training. While there are exceptions, e.g., in nuclear medicine where localized metabolic activity can be quantified as a specific uptake value (SUV), the detection and characterization of object location, shape, sharpness, and intensity, and the implications thereof, are subjective and accomplished by highly trained human observers. Today, these interpretations are critical for disease and patient management, including diagnosis, prognosis, staging, and assessment of treatment response. However, with few exceptions, this is largely a subjective operation with variable sensitivity and specificity and high inter-reader variability [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

In 2007, Segal et al. showed that careful characterization of the appearances of liver lesions in contrast-enhanced CT scans could be used to infer their molecular properties [11]. Similarly, in 2008, Brown et al. showed that quantitative analysis of gray-scale image texture on magnetic resonance (MR) scans of patients with oligodendroglioma could be used to predict their genetic signatures, specifically, co-deletion of chromosomes 1p and 19q [12]. These and other early examples showed that not only could appearances on non-invasive imaging be quantified, but that these data could illuminate fundamental molecular properties of cancers [13,14]. Early examples used “semantic features,” i.e., categorizations of human observations using a controlled vocabulary [15,16,17], and these have expanded to use “computational features” that are direct mathematical summarization of image regions. Together, semantic and computational feature classes are the basis of the new field of “radiomics” [18,19], defined as the “high-throughput extraction of quantitative features that result in the conversion of images into mineable data” [20,21] and feature prominently in what is today called “quantitative imaging” [22,23,24]. This chapter describes the radiomics workflow, including its strengths and its challenges, and highlights the integration of radiomics with clinical data and the molecular characterization of tissue, also known as “radiogenomics” [13,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], for the building of predictive models. It focuses on “conventional radiomics” (i.e., machine computation of human-engineered image features) [32]. The more recent developments in radiomics, including the use of artificial intelligence, or “deep learning,” to automatically learn informative image features for linking to clinical data (e.g., expression, outcomes) from a set of suitably labeled image and clinical data [33] will be discussed in detail in the final chapter of this book. Most examples in the literature focus on cancer, i.e., imaging and analysis of medical images of tumors. However, radiomics may be used to characterize any tissue, and so in the following we refer to the regions of imaging data to be analyzed as volumes of interest (VOIs).

1.2 PRINCIPLES AND RATIONALE OF RADIOMICS AND RADIOGENOMICS

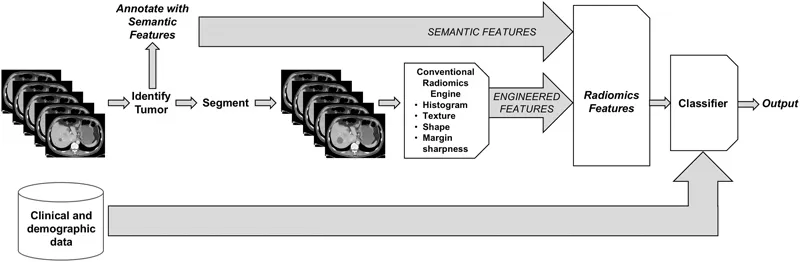

Figure 1.1 illustrates the radiomics workflow for any imaging dataset, which may be 2D, 3D, or of higher dimension. Component parts are: (1) identification of the location of the VOI to be analyzed, (2) annotation of the tissue with semantic features, (3) VOI segmentation, i.e., identification of the entire imaged volume of tissue to be analyzed, and (4) feature computation via human-engineered image features. In some cases, “delta” features [34,35,36,37,38] may be computed by comparing individual feature values derived from different images acquired at different times. Collections of imaging features may be also created that combine features computed from multiple imaging methods [14,39,40,41]. These imaging features may be summarized in a “feature vector.”

VOI identification: Each and every VOI to be processed must first be identified, either semi-automatically or manually by a radiologist or automatically using computer aided detection approaches. In cancer imaging, e.g., when multiple tumors are present in a single imaging study, human effort is generally required to identify those that are clinically relevant, as in the case of index lesions scored with RECIST (“response evaluation criteria in solid tumors”). When computing delta radiomics features, matching of tumors across observations will also be required.

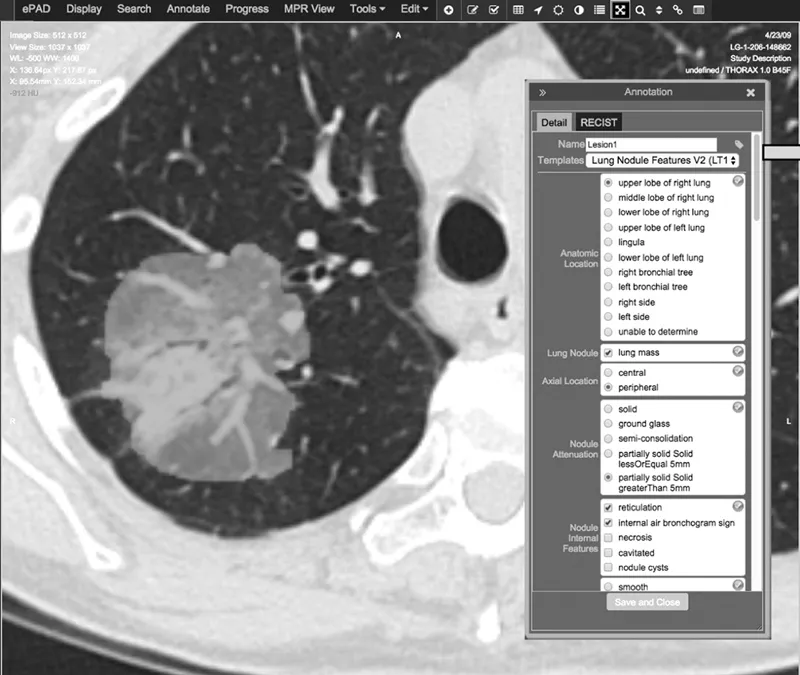

Annotation with semantic features: Semantic features are descriptive observations of image content. For example, semantic features of a lung tumor might include “left lower lobe,” “pleural attachment,” “spiculated,” “ground-glass opacity,” etc. However, extraction of semantic content from unstructured radiology reports may not be appropriate due to inconsistent and/or ambiguous vocabulary across observations and observers. Further, structured reports may not support the kinds of detailed observations required for making fine distinctions among tumor characteristics that may prove useful in classification or assessing response. Advances in structured reporting include the description of semantic features using a controlled vocabulary, such as RAD-LEX [42]. However, although much effort has been expended to develop more structured reporting, it is still not common in the broad radiology community. Currently, there are at least two systems that facilitate semantic annotation of radiological images using controlled vocabularies, ePAD [43] (Figure 1.2) and the Annotated Image Markup (AIM) data service plug-in [44] to ClearCanvas [45]. Some semantic features, such as location, other morbidities, etc., are meant to be complementary to computational features; others, such as “spherical,” “heterogeneous,” etc., are correlated with computational features [46,47]. One advantage of semantic annotations is that they are immediately translatable, i.e., they can be elicited in clinical environments without specialized algorithms (e.g., segmentation) or workstations. As such, they have shown interesting results in several radiogenomic studies [48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Figure 1.1 (See color insert.) Conventional radiomics workflow combining semantic and human-engineered computational features. These radiomics features can then be combined with clinical and demographic data, before the final classification stage, which generates an output such as benign/malignant, responder/non-responder, probability of 5-year survival, etc.

Figure 1.2 (See color insert.) Example of semantic annotation of a part solid part ground glass lung tumor using ePAD. Following tumor segmentation (green), either manually within ePAD or created via other means, an observer selects annotations using a custom template (built, e.g., using the AIM Template Builder [96]) or one of several available. The example in this figure shows a subset of the annotation topics that are required to complete this annotation.

VOI segmentation: Radiomics features can be extracted from arbitrary regions within the image volume: In cancer imaging, e.g., a given region may contain an entire tumor, a subset of the tumor (e.g., a habitat [55,56]; see also Chapter 7), and/or a peritumoral region [57,58,59] thought to be involved with or affected by the tumor. In all cases, these regions must be unambiguously identified (segmented) and input to the radiomics feature computation algorithms. This segmentation step is the single most problematic aspect of conventional radiomics workflows [60], as the features computed from tumor volumes may be extremely sensitive to the specification of the volume to be analyzed. Each combination of tumor type and image modality presents its own challenges (including volume averaging of tissues within each voxel, tumor contrast with surrounding/adjacent structures, image contrast-to-noise characteristics, and variations of image quality across vendor implementations and time). In addition, many algorithms require operator inputs, such as bounding boxes and/or seed points, and the segmentation outlines and radiomics features computed from them may be sensitive to these inputs. For exa...