- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Militarization

About this book

Repression, armed conflicts, interstate wars, the international arms trade, military regimes, and increasing worldwide military expenditures are all indications of one particularly significant development in world politics: global militarization. In this volume, an international group of scholars describe, explain, and evaluate the roots of this de

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

The State of the Art

1

Military Formations and Social Formations: A Structural Analysis

Johan Galtung

Introduction

With the total world budget for military systems rapidly approaching $300 billion, in other words about $75 per capita for each member of the human race,1 there is no doubt that the military formation is a major part of contemporary society. At the same time, there are about half a hundred regimes that can be characterized as military, and an additional number that, although not military in the formal sense of having come into being through a military coup, are relying on military support to the extent that the civilian government sometimes can be referred to as a front. If a young boy in most developing countries asks the question, How do I make a career in this society? the honest answer would probably be "join the military, it can lead you anywhere." In fact, the present growth rate of the military system is much higher in the Third World than in the First and Second Worlds, a factor that will be discussed later in this chapter.

The ultimate purpose of the military system is destruction—destruction of human lives, the man-made environment, and the environment in general. Deterrence is based on the probability that the system is both motivated toward and capable of destruction, first of the other side's military system and ultimately, as mentioned, of anything.2 The Indochina wars have provided the most frightening examples of what the human mind, combined with military organization, is able to concoct in terms of destructiveness. Given this purpose, the military system can be said to be a strange part of human society indeed, both in the sense of being "funny" and in the sense of being "alien." It drains resources and once in a while has to prove its destructive capability in order to remain credible. The idea of controlling its growth so as to arrive at a constant size, the idea of trimming this size downward, and the ultimate idea of eliminating the military system completely are, as ideas, logical consequences of the nature and expansion of the military system. As ideas they are old and have been relatively highly regarded in this century; in practice, the present situation bears ample testimony to the fact that these ideas have not been very effective. There must be some reasons for that, and the present chapter is concerned with some of those reasons. What maintains military systems? and Why do they exist?

Four Ways of Thinking About Military Systems

To give some answers to those questions, let us start by making two distinctions. One may choose to analyze military systems, both their software (manpower) and hardware (arms) components sui generis— i.e., as if they were isolated systems, detached from the social environment. Military systems sometimes invite this type of analysis: They command a separate ministry with a separate budget; the software is kept in separate quarters, often far away from other people; and the hardware—both its production and its storage—is kept well hidden, often even from most members of the military system themselves. In some countries, the military system actually constitutes a separate society with its own production facilities and its own distribution machinery, producing and distributing not only the materials that are necessary for the military system as such but everything else that is needed for the reproduction of the system—food, clothes, housing, medical services, schooling, etc. It is, in fact, a society within society, and to focus on it sui generis would appear highly warranted.3

But this type of approach neglects at least two very important factors. First, the military system is ultimately intended to be used, and to be used in a conflict. But a conflict can be analyzed as a conflict formation, consisting of parties and a conflict issue. To analyze the military system without taking this factor into account would be a little bit like analyzing a hospital without any reference to patients or diseases, or analyzing a school system without any reference to pupils. One might learn something, but the analysis would tend to remain very abstract, detached from social reality. Distinctions, or taxonomies, may be made between military systems that mainly operate on land (armies), at sea (navies), and in the air (air forces), as was done in the old days, or they may be made between military forces that are intended for megawar (nuclear capabilities, weather modification, artificially triggered tsunamis or earthquakes, etc., not to mention large-scale bacteriological and chemical warfare); macrowar (such as most of the systems used in the two world wars) and microwar (guerrilla actions, "terrorism," etc.)—superconventional, conventional, and subconventional systems would be more suitable classifications today. Such taxonomies are useful, but only insofar as they can be related to a structural analysis, using conflict formations as a basic analytical tool.

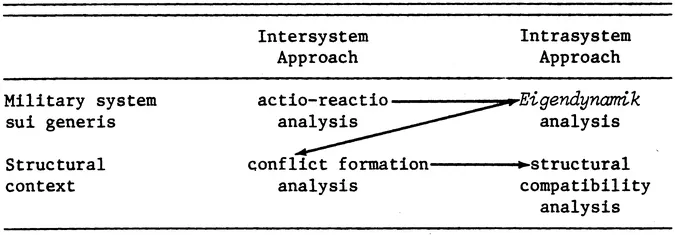

Table 1.1. Four approaches in analyzing military systems

The second neglected aspect is how the military system relates to the social structure in which it is embedded, the society that produces and reproduces the system. The degree of interdependence—the society forming the military system and vice versa—will become more pronounced as the military system becomes stronger and more "developed." Since the concern about military systems today to a large extent is a concern about their growth, there is every reason to pay particular attention to this interdependency.

Implicit in what has been said above is a second major distinction in analyzing military systems: the intersystem approach versus the intrasystem approach. Usually "system" stands for society in the sense of a polity, meaning, for all practical purposes, a country—sometimes organized as a nation-state. Just as one gets different perspectives on, for instance, disarmament or demilitarization processes depending on whether one focuses on the military system sui generis or on the general structure, different types of light are shed on the problem depending on whether one looks at relations between systems or what happens inside them.

Taken together, these distinctions give rise to a fourfold table (Table 1.1). Let us try to spell out typical perspectives arising from this map of analytical orientations, following the arrows since this sequence is more or less the way analysis has proceeded, and, one might add, progressed, in recent years.4

The Actio-Reactio Model

The actio-reactio approach seems outdated today, not because it will not give very adequate insights into many situations, but because it leads to high levels of mystification when taken too seriously. L. F. Richardson5 did a service by putting the model in mathematical form because doing so made its crudeness more evident. A differential equation presenting the level of armament in one country as a function of the increment of the armament in another country is a very good baseline model, not so much because of what it shows as because of the many things it obviously does not show. Such a model portrays the military system as being essentially other directed, propelled by what happens in other military systems, not by its own dynamics, or by the structure or structures in which it is embedded. It does not help to equip the differential equations with some parameters or constants if these are not tied explicitly to other variables; if they are, the insufficiency of this perspective is brought out more clearly since these variables have to be fetched from one or more of the other three categories in Table 1.1 (or from other sources). Parameters become ways of escaping theoretical exploration by focusing on curve fitting instead.

The Eigendynamik or Autistic Model

In the Eigendynamik model, the growth of the military system is seen as being propelled by internal forces, and since the focus is usually on the hardware component and how it is produced, the model is essentially an economistic one. In order to produce military hardware, the same economic factors are needed as for the production of any hardware: raw materials, capital, labor, research, and organization (in the sense of administrators, i.e., a mixture of managers and bureaucrats with the ratio of the mixture varying from system to system). This model, in and by itself, does not reveal any built-in expansionism, except in the usual sense that when there is an imbalance in the supply of factors for the production of anything, the tendency may be to fill up on the lagging factor(s), not to cut down on those that are in excess.6 Thus, if the raw materials are there, the labor is there, researchers have done their work so that the model of what to produce exists, and the whole administrative machinery is present, there will be a tendency to try to provide the missing capital rather than to send the raw materials back, dismiss the workers, let the research findings be shelved unused, and transfer the administrators to something else. In fact, this reaction is probably particularly likely if the people involved can prove convincingly that the lag is in one factor only, making it look very uneconomical not to fill up on that one.7

However, there are other strong factors in the internal dynamics that also cause expansion. First, there is the very simple circumstance that the military system is commanded by military people who, like most other people in a modern society, would like to have an expanding share of the total social product because their power and prestige are related to the military system's relative size inside the society. It is in that society that power and prestige are measured, not when the system is pitted against an enemy during a war—as wars, after all, are exceptional periods in human and social history. In order to justify their claims, military people use actio-reactio model reasoning or the Eigendynamik model type of reasoning, to at least keep their share of the social product constant.8

How successful they are depends on how successfully they are controlled by other sectors of society. If this control is relatively strong, expansion has to be achieved through other channels, and the most effective channel from the military point of view is to have the civilian sector want an expansion of the military sector because of what it can do to help the civilian sector. At this point, the reasoning shades over into the structural compatibility model: It becomes a question of what the military system does to the surrounding society.

It also belongs to the Eigendynamik model, however, because the reasoning remains so close to what has already been presented: It is essentially production oriented, and economistic. Human beings are involved in the production of military hardware as workers, researchers, capitalists, and bureaucrats, and an expansion of this aspect of the military system may also expand the power and prestige of these people. For that reason, such expansion might be as desirable to them as it is to the military people themselves. There is the question of how well coordinated these expansionist interests are, which may be a question of the same person appearing in multiple roles or having relatives and friends in other parts of the total system. The harmony of interest in expansion, as measured in power and prestige for military personnel, military researchers, and military bureaucrats and in terms of profit for the capitalist, is what is usually referred to as the military-industrial complex (MIC) or the military-bureaucratic complex (MBC) for the market and centrally planned economies, respectively. However, much too clear a line is usually drawn between the two types of economies. It might be much more fruitful to talk about the military-capitalist-bureaucrat-researcher complex (MCBRC), since that seems to be the type of alliance that is at work—"capitalist" meaning also the top administrators of centrally planned economic organizations ("state capitalists").

However, the military production system also has a great impact on the surrounding society, which is where the analysis shades over into the structural compatibility model. The system is capable of putting to use excess capital (which might produce inflation) or excess labor (meaning unemployed people, which would also include unemployed researchers, bureaucrats, and capitalists in times of real distress), thereby serving a Keynesian function in the economy.9 Remarkable in this connection is the absorptive capacity of the military system. It is simultaneously capital intensive and labor intensive as it can absorb any amount of capital into its hardware components and any amount of any kind of labor into its software components. There has to be a reason, however, to accept the military as the recipient of all these economic factors, and it is at this point, of course, that the politics of tension management become important. The thesis that there should be some kind of proportionality between the rate of increase in military capacity and the tension level seems reasonable, but hardly unconditional. Thus, a sufficiently autocratic regime might simply increase its military capacity regardless of what the tension level is for the reasons mentioned in discussing the intrasystem approach models. However, if a tension image can be produced, it probably will be produced, for no other reason than because of the mores surrounding the military machinery: There is an assumption that the machinery should be relevant for conflict in an intersystem setting.

If there should happen to be two systems—two countries, blocs, alliances, etc.—tied to each other because of a credible conflict but with the same internal economic problems, then they might both make use of the Eigendynamik model as an approach to stabilize their economies. It should be pointed out that this utilization can hardly be successfully analyzed in terms of a quest for profit or power; it should be seen instead as parallel quests for equilibrium in the economic systems. If at the same time there is a tension between the two systems, it will seem as though the actio-reactio model is at work, each system being inspired in its military buildup by what it observes in the other system. In reality, however, the notion of two parallel autistic developments might be more useful in understanding what is happening.10 At this point, one should not be confused by the use of "incidents" as a part of the tension-management process. A submarine in the coastal waters of one country and an infraction of the airspace of another might be used by either to justify its military buildup. But one should not disregard the obvious hypothesis that there could be a gentlemans' agreement, according to which one incident would be traded off for the other, which might serve the joint interest of the same type of people in both countries of increasing their share of the total economy.

A critical point to look for in justifying this kind of analysis would not be so much to what extent the civilian and the military sectors are intertwined but the extent to which the military sector is a mirror image of the civilian sector, even when ke...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- PART 1 THE STATE OF THE ART

- PART 2 GLOBAL MILITARIZATION: CRUCIAL TRENDS AND LINKS

- PART 3 LOCAL EXPERIENCES: HISTORICAL DIMENSIONS

- PART 4 THE SEARCH FOR ALTERNATIVES

- About the Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Global Militarization by Peter Wallensteen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.