- 390 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New York School

About this book

FROM 1947 TO 1951, more than a dozen Abstract Expressionists achieved "breakthroughs" to independent styles. 1 During the following years, these painters, the first generation of the New York School, received growing recognition nationally and globally, to the extent that American vanguard art came to be considered the primary source of creative ideas and energies in the world, and a few masters, notably Pollock, de Kooning, and Rothko, were elevated to art history's pantheon. Younger artists who entered their circle in the early fifties-the early wave of the second generation-such as Larry Rivers, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Allan Kaprow, Joan Mitchell, Robert Rauschenberg, and Richard Stankiewicz (to list some of the better known), were also acclaimed, but with a few exceptions, their reputations had gone into decline by the end of the fifties. In the following decade, the second generation was eclipsed by a third generation, the innovators of Pop, Op, Minimal, and Conceptual Art. (Any notion of a generation of artists is necessarily arbitrary, of course. The term "generation," as it is used here, refers to a group of artists close in age who live in the same neighborhood at the same time, and to a greater or lesser degree, know each other and partake of a similar sensibility, a shared outlook and aesthetic.)

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1

The Milieu of the New York School in the Early Fifties

AROUND 1950, the first generation of the New York School attracted a small group of young artists who formed the early wave of the second generation. It was natural for these newcomers to be drawn to Abstract Expressionism, so struck were they by its expressive power, high quality, freshness or radicality, and aspiration. Moreover, the older artists’ passionate and serious commitment to art, their perseverance, often in the face of great personal deprivation, their audacity in painting only what they needed to, each relying on himself or herself as the sole authority, impressed young artists, even striking many as heroic. Frank O’ara, a poet-curator-critic, recalled: “Then there was great respect for anyone who did anything marvellous: when Larry [Rivers] introduced me to de Kooning I nearly got sick … besides there was then a sense of genius. Or what Kline used to call ‘the dream’”1

The New York School constituted a loose community which was primarily an open network based on personal relationships, more social than aesthetic in nature. John Ferren accurately defined it as “a state of friendship. Not necessarily love or agreement but, definitely, respect and the personal recognition of the other and yourself being involved in the same thing. That thing is conveniently labeled Abstract-Expressionism by the critics. It isn‘t quite so simple. If Abstract-Expressionism is the largest vortex, the antithesis, the rejections, the yet unmade developments are also there.”2 Ferren went on to say: “‘He should be in’” really meant “‘He is involved somewhere in the tensions and polarities of our thinking and, through his work, has made us see it’”3

These polarities, as the early wave saw them, were in the realm of gesture or painterly or action painting, ranging from abstraction to representation. The artists who worked within these broad limits all believed themselves to be in the vanguard, for the style was both open to original developments and also the butt of considerable art-world and public hostility.

De Kooning and Hofmann, innovators of gestural Abstract Expressionism, inter ested the early wave most. Both were available to their juniors to a greater extent than such contemporaries as Pollock, Still, Rothko, and Newman, who by 1951 had largely removed themselves from the “downtown” art scene (south of Twenty-third Street in Manhattan). A newcomer could enroll in Hofmann’s school on Eighth Street; meet de Kooning and other painters stylistically related to him, e.g., Kline, Jack Tworkov, and Esteban Vicente, almost any night at the Cedar Street Tavern or at the Wednesday and Friday meetings at the Club (organized by the first generation in 1949), or casually on East Tenth Street, in the center of the neighborhood where most New York School artists lived and worked at that time.

Moreover, both de Kooning and Hofmann were inspirational figures. With his first one-man show in 1948, de Kooning was established as a major Abstract Expressionist, second only to Pollock in reputation, and soon to be the most influential artist of his generation. De Kooning was admired for his integrity and dedication to art—qualities which were thought by many (including me) to be embodied in his painting. He was also a brilliant conversationalist, passionate and convincing in his insights into art and contemporary experience, his persuasiveness augmenting the impact of his pictures. Hofmann’s painting was not regarded as highly as de Koonings, but he was widely considered to be America’s greatest art teacher.4 As a man, he was robust and warm; enthusiastic, expansive, and assured; able to play a commanding paternal role and simultaneously to treat his students as colleagues. Furthermore, he possessed the impressive aura of history. Born in 1880, Hofmann had lived in Paris from 1904 to 1914—the heroic decade of twentieth-century art—had been a friend of the innovators of Fauvism and Cubism; had learned of their ideas at first hand, possibly even contributing some of his own; and as early as 1915, had opened his first school in Munich, which in the twenties began to attract American art students who would broadcast at home his abilities as a teacher.

There were sharp differences between the attitudes of Hofmann and de Kooning, Hofmann more systematic, basing his aesthetics on a belief in universal laws which governed nature and art, although he also affirmed the primacy of the artist’s spiritual and intuitive feeling into both; de Kooning strongly anti-doctrinaire, rooting his painting in the immediacy of his experience here and now. Hofmann taught that painting at its highest should reveal spiritual reality, an aspiration that appealed to many of his students. His aesthetics were geared to the creation of suggested depth or space which, not being a tangible pictorial property, was transmaterial or spiritual.5 De Koonings complicated, restless and ambiguous, raw and violent painting appeared to be shaped by urban living—the total feeling of the city rather than its appearances—conveying his existential reaction to the world outside and inside the studio. Moreover, the gestures composing de Kooning’s pictures were painted directly, implying “honesty” their final aggregation seemed “found” in a forthright struggle of creation. His work struck young artists as unnervingly “real” and emotionally genuine—and this inspired emulation.

There was also the sense in de Kooning’s work that he was perpetually taking “risks,” that is, refusing to lapse comfortably into an habitual style, and instead, was venturing courageously beyond the already known, aspiring to paint something that could not be predicted and ultimately, to the unattainable. “Going for broke” as an ambition was powerfully appealing, as a recollection of Friedel Dzubas revealed, even though he was appalled at the psychic costs of de Kooning’s effort. “I was aware to what degree he was torturing himself, really, in forever trying to create some sort of absolute answer, an absolute masterpiece. … I saw him in East Hampton starting something, and after the first week, people would sneak in to take a look. ‘Beautiful,’ they’d say, it looked absolutely right. And then over the next two months, day by day, whatever was right he would slowly destroy, out of this incredible pride.”6

Despite their differences in outlook, de Kooning and Hofmann shared a number of basic conceptions of what a painting ought to be, the ideas of the one reinforcing those of the other in the minds of young artists. And these ideas presented challenging difficulties and opened up enormous opportunities for individual development. In brief, both older artists believed in the viability of subject matter, that is, recognizable images in pictorial depth; of Cubist-inspired relational design; and of masterly drawing and painting.

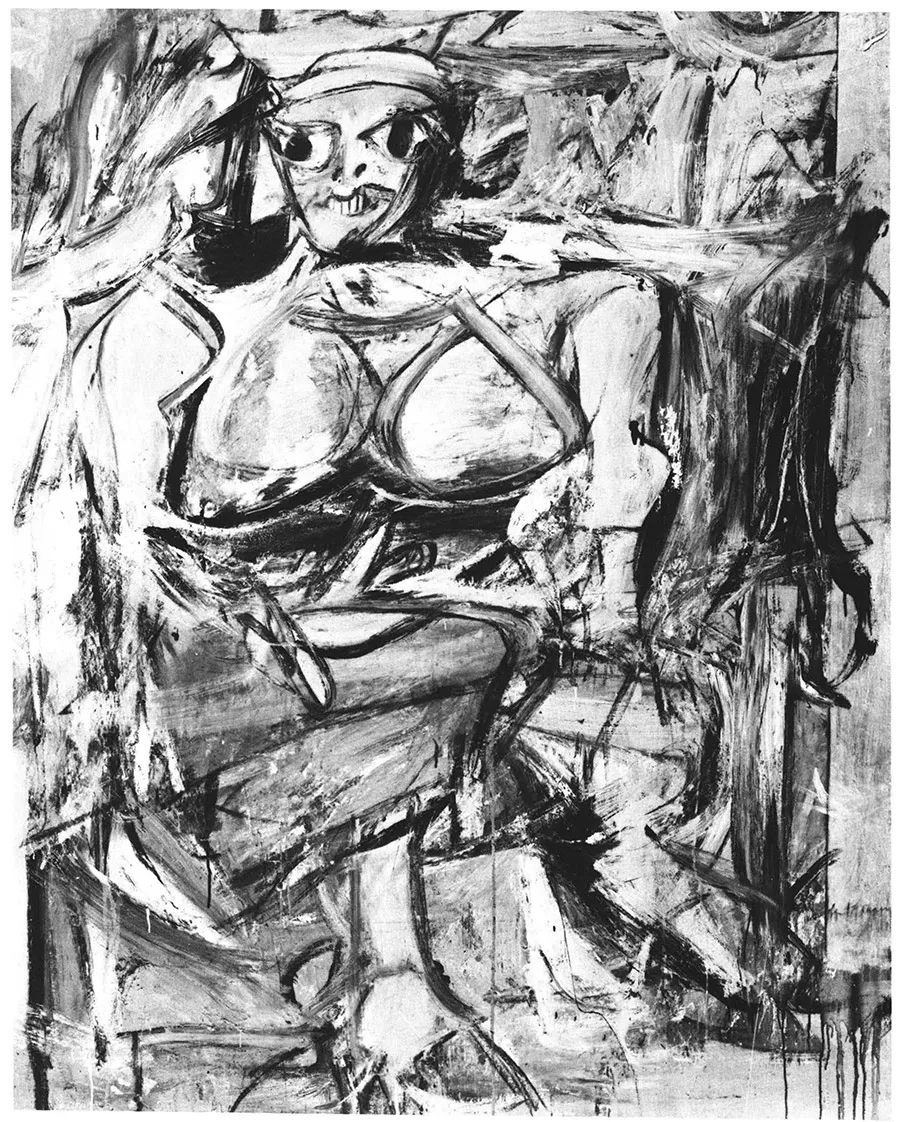

The two Abstract Expressionists insisted that to be modernist, art need not be abstract. Figuration offered a genuine option. Indeed, their paintings, even the most abstract, have a source in nature. Moreover, Hofmann demanded that his students begin with observable phenomena; the main activity in his classes was drawing from a live model or still life. De Kooning also made a strong case for subject matter, and naturally so, for he was painting his Woman series, which in itself was a strong stimulus to figurative art. The first of these canvases was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and was one of the most reproduced pictures by a painter identified with Abstract Expressionism during the fifties. In a lecture at the museum in 1950 (published the following year), de Kooning ridiculed aesthetician-artists who made an issue of abstraction-versus-representation, and who wanted to “abstract” the art from art. In the past, art had

… meant everything that was in it—not what you could take out of it. … For the painter to come to the “abstract” … he needed many things. These things were always things in life—a horse, a flower, a milkmaid, the light in a room through a window made of diamond shapes maybe, tables, chairs, and so forth. … But all of a sudden, in that famous turn of the century, a few people thought they could take the bull by the horns and invent an esthetic beforehand. … with the idea of freeing art, and … demanding that you should obey them. … The question, as they saw it, was not so much what you could paint but rather what you could not paint. You could not paint a house or a tree or a mountain. It was then that subject matter came into existence as something you ought not to have.7

De Kooning concluded that the non-objective aesthetician-artists, in trying to make “something” from the “abstract” or “nothing” quality that had always inhered in specific things, lost the aesthetic quality they sought to the exclusion of everything else.

1 Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950–52.

75⅞” × 58”. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

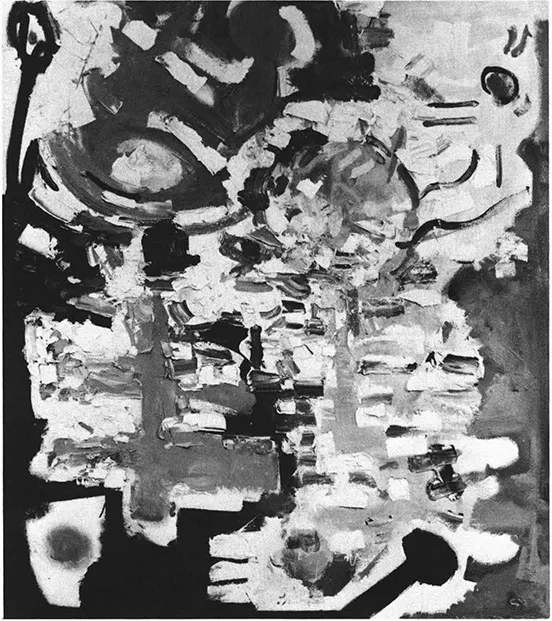

Both de Kooning and Hofmann insisted that contemporary artists approach subject matter in a way different from past artists. For de Kooning, today’s “reality” could only be apprehended in sudden “glimpses” all at once in a total experience, and this could not be achieved by painting the appearance of things. Hofmann taught: “There are bigger things to be seen in nature than the object.”8 Visual phenomena could not be copied dumbly by modernist artists. Nor could they continue to use academic conventions. The primary problem that Hofmann posed to his students was to translate the volumes and voids of what was seen in the world into planes of color, in accord with the two-dimensional character of the picture surface—a “modernist” approach. And then the crucial action was to structure these planes into “complexes,” every component of which was to be reinvested with a sense of space—depth or volume—without sacrificing flatness. To achieve this simultaneous two- and three-dimensionality, Hofmann devised the technique of “push and pull”—an improvisational orchestration of areas of color, or as he liked to put it, an answering of force with counterforce. “The essence of my school: I insist all the time on depth. … No perspective [or modeling which violates two-dimensionality] but plastic depth.”9

As Hofmann’s former student, Allan Kaprow, summed it up, all paintings, despite their diversity,

… submit to certain basic laws. Each picture is an organic whole whose parts are distinct but relate strictly to the larger unit. Since the painting surface, being flat, is only a metaphoric field for activity, its nature as a metaphor must be preserved. That is to say an exact balance had to be struck between the planar uniformity of the canvas and the organic (i.e. three-dimensional) nature of the event set into operation on it. This, we found out, was not easy at all … So this part-to-whole problem occupied the class continually and further broke down into the study of certain special particulars of all painting; color, that is, hue, tone, chroma, intensity, its advancing and receding properties, its expansiveness or contractiveness, its weight, temperature, and so forth; and in the area of so-called form, the way in which these act together in points, lines, planes, and volumes.10

And yet, despite Hofmann’s concern with systematic picture-making, he warned against allowing preconceptions of any kind to govern creation. As he said in 1949: “At the time of making a picture, I want not to know what I’m doing; a picture should be made with feeling, not with knowing. The possibilities of the medium must be sensed.”11

Like Hofmann, de Kooning painted in depth, for the human anatomy, which was the source of most of his imagery no matter how abstract, is bulky and exists in space. He refused to deny its volume, even though at the same time he insisted on maintaining the picture plane, his painterly brushstrokes asserting the physicality of the canvas which supported them. Moreoever, de Kooning scoffed at making flatness a modernist dogma, calling it old-fashioned. He said: “Nothing is that stable.”12

Given Hofmann’s emphasis on drawing with nature in mind, and the challenge of de Kooning’s Woman series, it is not surprising that many artists in the early wave adopted figuration, and even took the step to a more explicit representation. But they also heeded the lessons of modernist art learned from the paintings of the Abstract Expressionists and of older masters, e.g., Matisse, Bonnard, and particularly Picasso, Braque, and other Cubists.

2 Hans Hofmann, Fantasia in Blue, 1954.

6...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The Milieu of the New York School in the Early Fifties

- 2 The Community of the New York School

- 3 The Colonization of Gesture Painting

- 4 Frankenthaler, Mitchell, Leslie, Resnick, Francis, and Other Gesture Painters

- 5 Gestural Realism

- 6 Rivers, Hartigan, Goodnough, Müller, Johnson, Porter, Katz, Pearlstein, and Other Gestural Realists

- 7 Assemblage: Stankiewicz, Chamberlain, di Suvero, and Other Junk Sculptors

- 8 The Duchamp-Cage Aesthetic

- 9 Rauschenberg and Johns

- 10 Environments and Happenings: Kaprow, Grooms, Oldenburg, Dine, and Whitman

- 11 Hard-Edge and Stained Color-Field Abstraction, and other Non-gestural Styles: Kelly, Smith, Louis, Noland, Parker, Held, and Others

- 12 The Recognition of the Second Generation

- 13 The New Academy

- 14 Circa 1960: A Change in Sensibility

- Appendix A: First-Generation Painters, Dates and Places of Birth

- Appendix B: Second-Generation Artists, Dates and Places of Birth, Art Education, and One-Person Shows in New York, 1950–1960

- Bibliography

- List of Illustrations

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access New York School by Irving Sandler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.