eBook - ePub

Mozambique

From Colonialism To Revolution, 1900-1982

Barbara Isaacman, Allen Isaacman

This is a test

Share book

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mozambique

From Colonialism To Revolution, 1900-1982

Barbara Isaacman, Allen Isaacman

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on oral interviews as well as written primary sources, the authors of this book focus on the changing and complex Mozambican reality. They focus their study on the changing and complex Mozambican reality to avoid depicting the colonized people as passive victims..

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Mozambique an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Mozambique by Barbara Isaacman, Allen Isaacman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Politique africaine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

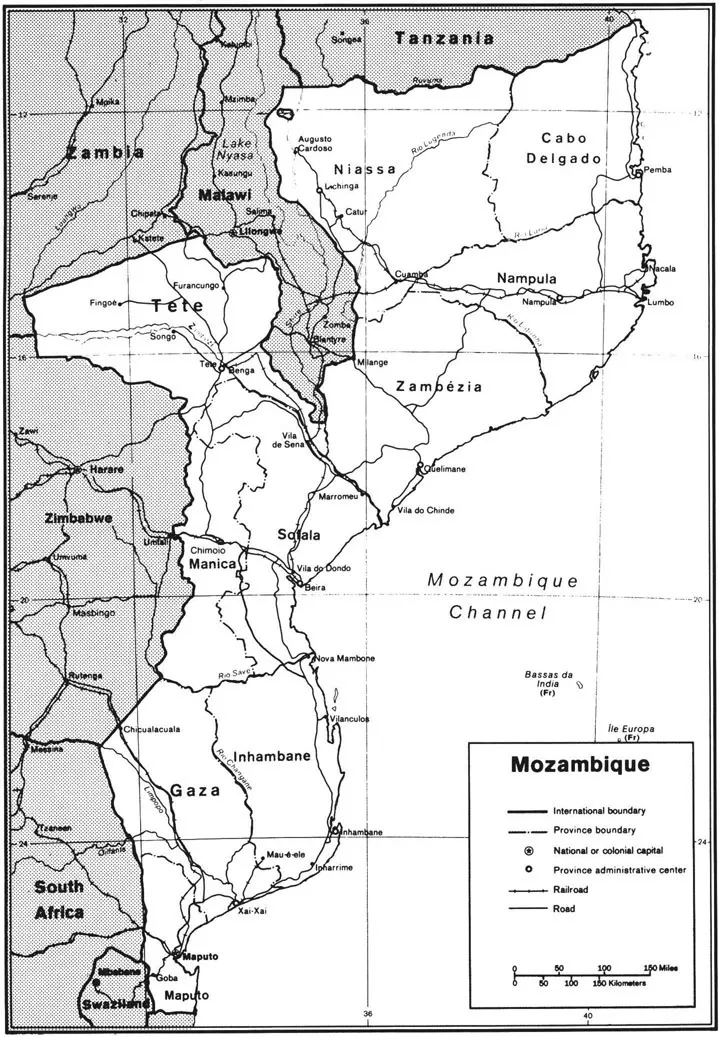

Straddling the Indian Ocean and the volatile world of racially divided Southern Africa, Mozambique has assumed an increasingly strategic international position. Its 2,000-mile (3,200-kilometer) coastline and three major ports of Maputo, Beira, and Nacala—all ideally suited for naval bases—have long been coveted by the superpowers (see Figure 1.1). These ports, from which a great power could interdict, or at least disrupt, Indian Ocean commerce and alter the balance of power in Southern Africa, also offer international gateways to the landlocked countries of the region. Through them Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana, Swaziland, and Malawi can reduce their economic dependence on South Africa.

No less important is Mozambique’s proximity to South Africa and Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia), which gained its independence in 1980 with substantial military and strategic assistance from Mozambique. A progressive regime in Mozambique provides inspiration to the 20 million oppressed South Africans as well as support to the African National Congress (ANC), which is leading the liberation struggle. As the spirit of insurgency spreads within South Africa, the region may well become a zone of international conflict in which Mozambique would figure prominently.

The young nation’s strategic importance, however, transcends its geographic position. Mozambique, according to Western analysts, has enormous mineral potential.1 The world’s largest reserve of columbotantalite—used to make nuclear reactors and aircraft and missile parts—is located in Zambezia Province, and the country is the second most important producer of beryl, another highly desired strategic mineral. The country’s coal—10 million tons will be produced annually by 1987—has also attracted the attention of such energy-starved countries as Italy, France, Japan, and East Germany. The Cahora Bassa Dam,2 the largest in Africa, has the potential to meet much of the energy needs of Central and Southern Africa. Large natural gas deposits and the increasing likelihood of offshore oil enhance Mozambique’s role as an energy producer.

The goal of the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), the country’s liberation movement and governing party, to create “Socialism with a Mozambican Face” and to break out of the spiral of impoverishment and underdevelopment carries important ideological implications for the continent as a whole. Whereas most African nationalist movements were

Figure 1.1 Mozambique, 1982

Source: U.S. government publication, 1982.

content to capture the colonial state, FRELIMO’s ten-year armed struggle radicalized it. Political independence became only the first step in the larger struggle to transform basic economic and social relations.

“Socialism with a Mozambican Face,” as expressed by FRELIMO, is not a variant of the vaguely defined form of African socialism that was in vogue in the late 1960s. Nor is it an Eastern European model transplanted onto Mozambican soil. To Mozambican leaders it means a synthesis of the concrete experiences and lessons of the armed struggle—experimentation, self-criticism, self-reliance, peasant mobilization, and the development of popularly based political institutions—and the contemporary Mozambican reality with the broad organizing principles of Marxism-Leninism. Listen to Mozambique’s President Samora Machel:

Marxism-Leninism did not appear in our country as an imported product. Mark this well, we want to combat this idea. Is it a policy foreign to our country? Is it an imported product or merely the result of reading the classics? No. Our party is not a study group of scientists specializing in the reading and interpretation of Marx, Engels and Lenin.

Our struggle, the class struggle of our working people, their experiences of suffering enabled them to assume and internalize the fundamentals of scientific socialism. … In the process of the struggle we synthesized our experiences and heightened our theoretical knowledge…. We think that, in the final analysis, this has been the experience of every socialist revolution.3

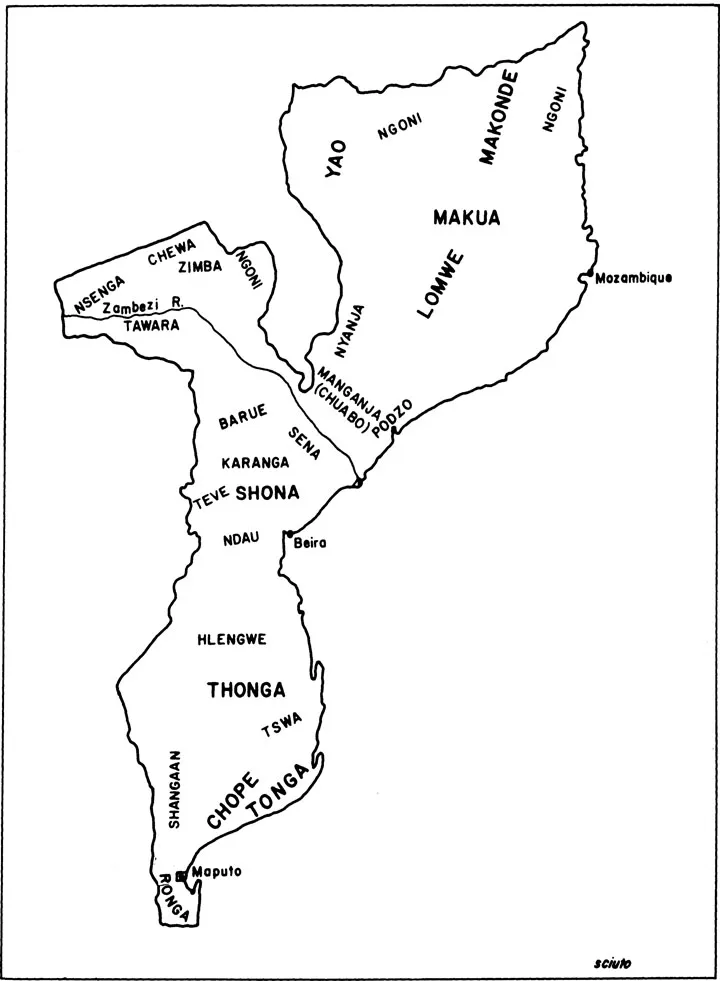

Mozambique’s social experiment also merits critical attention because of its highly visible campaign against tribalism and racism. In a continent marred by ethnic, religious, and regional conflict, the intensity with which the Mozambican government is combating these divisive tendencies is unprecedented. It is no easy task. Mozambique’s population—12 million in 19804—is divided into more than a dozen distinct ethnic groups (see Figure 1.2 and Table 1.1). Although they have some common cultural and historical experiences, each has its own language, material conditions, identity, and heritage. The patrilineal, polytheist Shona of central Mozambique have little in common either with the matrilineal, Islamized Yao and Makua to the north or with the Shangaan to the south, whose ancestors migrated from South Africa only a century ago. Historical rivalries, fanned by the Portuguese colonial strategy of divide-and-rule, heightened particularistic tendencies. FRELIMO is also committed to the creation of a nonracial society in which the 20,000 whites and somewhat larger number of Asians enjoy the full rights of Mozambican citizenship. Although impressed with the government’s vigor in attacking racism, skeptics, both black and white, question whether Machel’s policies are not naively attempting to jump over history.

Despite its uniqueness, Mozambique shares with other African nations the host of problems associated with underdevelopment. These include the lack of transforming industries and skilled workers, a staggering level of illiteracy—more than 95 percent at the time of independence5—the widespread incidence of debilitating diseases, a high infant mortality rate, and the absence of internal transportation and communications networks.

Figure 1.2 Ethnie Groups in Mozambique

Source: Thomas H. Henriksen, Mozambique: A History (London, 1978).

Table 1.1 Population, 1980 and 1981

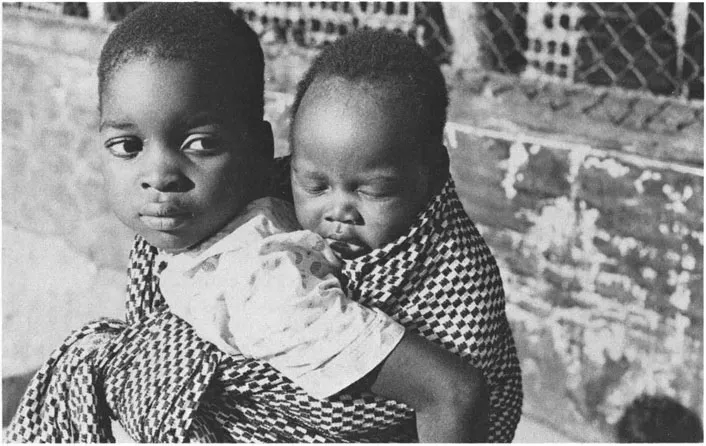

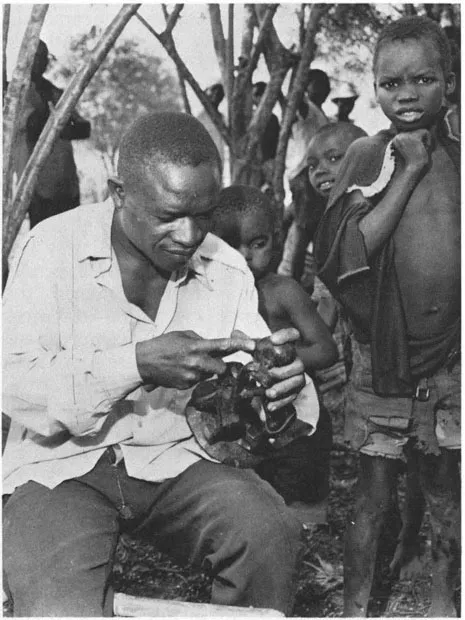

Faces (Credits: Ricardo Rangel; Mozambique Ministry of Information)

In 1978 the per capita gross national product (GNP) was estimated at $140, the lowest in all of Southern Africa.6 And although the terrain is fertile, only 10 percent of the land is under cultivation and food shortages pose a recurring problem.

To understand the enormous economic, social, and political difficulties the young nation faces requires an examination of the precolonial and colonial periods. Impoverishment and inequality, rooted at least as far back as the sixteenth century, dramatically increased as a direct consequence of the imposition of colonial-capitalism during the early years of this century. Yet if underdevelopment, oppression, and mass deprivation constitute recurring themes in Mozambican history, so, too, does the long tradition of resistance—a tradition that dates back to the arrival of Portuguese merchants, settlers, and missionaries in the sixteenth century.

We have attempted to focus our study on the changing and complex Mozambican reality and to avoid depicting the colonized people as passive victims. Nevertheless, it must be emphasized that events outside Mozambique increasingly narrowed the range of local choices; and as the country became progressively incorporated in the world capitalist economy and the Portuguese imperial network, all ethnic groups and indigenous social classes correspondingly lost their autonomy. Their future became inextricably bound to shifting international realities. The demand for slaves, the discovery of gold in South Africa and the need for migrant Mozambican labor, changing commodity prices on the world market, and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military support for the Portuguese colonial regime in its war against FRELIMO all helped to shape the course of Mozambican history.

Throughout the book we have sought to weave these external factors into our broader discussion of the changing Mozambican reality. Chapter 2 focuses on the patterns of interaction among different social groups, the process by which Mozambique became incorporated into the world economy, and the efforts of various Mozambican societies and social classes within them to maintain their autonomy in the face of Portuguese imperialism. It is followed by a discussion in Chapter 3 of Portuguese rule, which highlights the various, and at times contradictory, strategies the colonial state used to extract Mozambique’s human and natural resources and the social cost the Mozambicans paid. But the people of Mozambique—peasants and workers, old and young, women and men—were more than merely victims of oppression and objects of derision. In a variety of ways, discussed in Chapter 4, they asserted their dignity and struggled to limit colonial exploitation. Ultimately, this spirit of insurgency, coupled with Portugal’s intransigence, convinced a number of dissidents that only through armed struggle could independence be gained. Chapter 5 examines this struggle, the radicalization of FRELIMO, and the attempts of Lisbon and its NATO allies to maintain Portuguese hegemony. Having captured the colonial state, FRELIMO faced the more difficult task of creating a nation and a new socialist political system. Chapter 6 treats, in a necessarily tentative way, the problems FRELIMO has confronted in the political arena and the degree to which it has managed to overcome them. The subsequent chapter examines FRELIMO’s efforts to set in motion an economic transformation based on broad socialist principles and the serious difficulties that have frustrated many of its programs. The final chapter outlines the new nation’s efforts to pursue an independent foreign policy in an increasingly hostile international environment.

Given the book’s broad scope, we have tried to organize it to meet the needs of a variety of readers. The discussion, drawn from oral interviews as well as written primary and secondary sources, is pitched at a fairly high level of generalization to make it easily intelligible to readers who have little familiarity with Mozambique. Names and acronyms that recur regularly appear in a glossary and list of abbreviations at the end of the book. The notes contain some long explications and extensive citations for those students and researchers who wish more information on points of particular interest, and we also recommend a small number of books and dissertations in English for those who wish to delve further into various aspects of Mozambican history. Because economic issues are likely to determine the future success or failure of the Mozambican revolution, we have included in an appendix the Economic and Social Directives of the Fourth Party Congress of FRELIMO (April 1983), which we obtained just as this book went to press.