eBook - ePub

International Institutions And State Power

Essays In International Relations Theory

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The essays in this book trace the development of the author's thinking about international institutions between 1980 and 1988. The introduction, written especially for this volume, summarizes and defends the "neoliberal institutionalism" that he advocates as a framework for understanding world politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Institutions And State Power by Robert O Keohane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Global Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Neoliberal Institutionalism: A Perspective on World Politics

Even those observers of contemporary world politics who have emphasized the importance of transnational relations agree that "states have been and remain the most important actors in world affairs" (Keohane and Nye, 1972:xxiv). Furthermore, they recognize that international systems are decentralized: "Formally, each is the equal of all the others. None is entitled to command; none is required to obey" (Waltz, 1979:88). Although the term "anarchy" is loaded and potentially misleading because of its associations with chaos and disorder, it characterizes world politics in the sense that world politics lacks a common government (Axelrod and Keohane, 1985:226). "In the absence of agents with system-wide authority, formal relations of super- and subordination fail to develop" (Waltz, 1979:88).

Yet it is also generally agreed that anarchy implies neither an absence of pattern nor perpetual warfare: "world government, although not reliably peaceful, falls short of unrelieved chaos" (Waltz, 1979:114). It would not be true to say of Europe in 1988 what Hobbes declared in 1651: "Persons of sovereign authority, because of their independency, are in continual jealousies and in the state and posture of gladiators, having their weapons pointing and their eyes fixed on one another—that is, their forts, garrisons, and guns upon the frontiers of their kingdoms, and continual spies upon their neighbors—which is a posture of war" (Hobbes, 1651/1958:108, Part 1, Ch. 13). Kenneth Waltz acknowledges that "world politics, although not formally organized, is not entirely without institutions and orderly procedures" (Waltz, 1979:114).

To understand world politics, we must keep in mind both decentralization and institutionalization. It is not just that international politics is "flecked with particles of government," as Waltz (1979:114) acknowledges; more fundamentally, it is institutionalized. That is, much behavior is recognized by participants as reflecting established rules, norms, and conventions, and its meaning is interpreted in light of these understandings. Such matters as diplomatic recognition, extraterritoriality, and the construction of agendas for multilateral organizations are all governed by formal or informal understandings; correctly interpreting diplomatic notes, the expulsion of an ambassador, or the movement of military forces in a limited war all require an appreciation of the conventions that relate to these activities.

Thinking about International Institutions

The principal thesis of this book is that variations in the institutionalization of world politics exert significant impacts on the behavior of governments. In particular, patterns of cooperation and discord can be understood only in the context of the institutions that help define the meaning and importance of state action. This perspective on international relations, which I call "neoliberal institutionalism," does not assert that states are always highly constrained by international institutions. Nor does it claim that states ignore the effects of their actions on the wealth or power of other states.1 What I do argue is that state actions depend to a considerable degree on prevailing institutional arrangements, which affect

- the flow of information and opportunities to negotiate;

- the ability of governments to monitor others' compliance and to implement their own commitments—hence their ability to make credible commitments in the first place; and

- prevailing expectations about the solidity of international agreements.

Neoliberal institutionalists do not assert that international agreements are easy to make or to keep: indeed, we assume the contrary. What we do claim is that the ability of states to communicate and cooperate depends on human-constructed institutions, which vary historically and across issues, in nature (with respect to the policies they incorporate) and in strength (in terms of the degree to which their rules are clearly specified and routinely obeyed) (Aggarwal, 1985:31). States are at the center of our interpretation of world politics, as they are for realists; but formal and informal rules play a much larger role in the neoliberal than in the realist account.

Neoliberal institutionalism is not a single logically connected deductive theory, any more than is liberalism or neorealism: each is a school of thought that provides a perspective on world politics. Each perspective incorporates a set of distinctive questions and assumptions about the basic units and forces in world politics. Neoliberal institutionalism asks questions about the impact of institutions on state action and about the causes of institutional change; it assumes that states are key actors and examines both the material forces of world politics and the subjective self-understandings of human beings.2

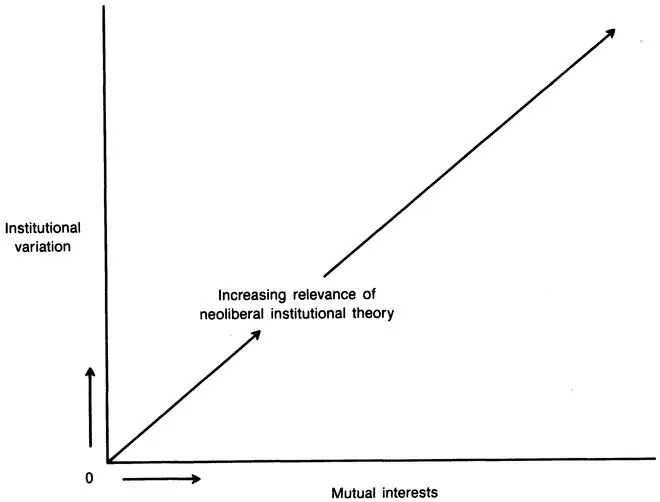

The neoliberal institutionalist perspective developed in Part 1 of this volume is relevant to an international system only if two key conditions pertain. First, the actors must have some mutual interests; that is, they must potentially gain from their cooperation. In the absence of mutual interests, the neoliberal perspective on international cooperation would be as irrelevant as a neoclassical theory of international trade in a world without potential gains from trade. The second condition for the relevance of an institutional approach is that variations in the degree of institutionalization exert substantial effects on state behavior. If the institutions of world politics were fixed, once and for all, it would be pointless to emphasize institutional variations to account for variations in actor behavior. There is, however, ample evidence to conclude both that states have mutual interests and that institutionalization is a variable rather than a constant in world politics. Given these conditions, cooperation is possible but depends in part on institutional arrangements. A successful theory of cooperation must therefore take into account the effects of institutions.

FIGURE 1.1 Conditions for operation of neoliberal institutionalism

The two conditions of mutual interest and institutional variation are graphically portrayed in Figure 1.1.

Organizations, Rules, and Conventions

Chapter 7 discusses in detail what I mean by "institutions" and how I think that international institutions should be studied. I define institutions as "persistent and connected sets of rules (formal and informal) that prescribe behavioral roles, constrain activity, and shape expectations." We can think of international institutions, thus defined, as assuming one of three forms:

1. Formal intergovernmental or cross-national nongovernmental organizations. Such organizations are purposive entities. They are capable of monitoring activity and of reacting to it, and are deliberately set up and designed by states. They are bureaucratic organizations, with explicit rules and specific assignments of rules to individuals and groups.3 Hundreds of intergovernmental organizations exist, both within and outside the United Nations system. Cross-national nongovernmental organizations are also quite numerous.4

2. International regimes. Regimes are institutions with explicit rules, agreed upon by governments, that pertain to particular sets of issues in international relations. In Oran Young's terminology, they constitute "negotiated orders" (Young, 1983:99). Examples include the international monetary regime established at Bretton Woods in 1944, the Law of the Sea regime set up through United Nations-sponsored negotiations during the 1970s, and the limited arms control regime that exists between the United States and the Soviet Union.5

3. Conventions. In philosophy and social theory, conventions are informal institutions, with implicit rules and understandings, that shape the expectations of actors. They enable actors to understand one another and, without explicit rules, to coordinate their behavior. Conventions are especially appropriate for situations of coordination, where it is to everyone's interest to behave in a particular way as long as others also do so. More specific contractual solutions—or regimes in the sense used earlier—are necessary to deal with prisoners' dilemma (PD) problems of major significance.6 But as Russell Hardin emphasizes, conventions do not merely facilitate coordination in pure coordination situations; they also affect actors' incentives. Since nonconformity to the expectations of others entails costs (Hardin, 1982:175), conventions provide some incentive not to defect, even in situations when, without the convention, it would pay to do so. Conventions typically arise as "spontaneous orders," in Young's terminology. Traditional diplomatic immunity was a convention in this sense for centuries before being codified in two formal international agreements during the 1960s.7 Reciprocity is also a convention: political leaders expect reciprocal treatment, both positive and negative, and are likely to anticipate that they will incur costs if they egregiously violate it—for example, by reacting disproportionately to barriers against their exports imposed by other states.

In thinking about international institutions, it is important to keep conventions in mind and to refrain from limiting one's frame of reference to formal organizations or regimes. Conventions are not only pervasive in world politics but also temporally and logically prior to regimes or formal international organizations. In the absence of conventions, it would be difficult for states to negotiate with one another or even to understand the meaning of each other's actions. Indeed, international regimes depend on the existence of conventions that make such negotiations possible.

Institutionalization in the sense used here can be measured along three dimensions:

- Commonality. The degree to which expectations about appropriate behavior and understandings about how to interpret action are shared by participants in the system;

- Specificity. The degree to which these expectations are clearly specified in the form of rules;

- Autonomy. The extent to which the institution can alter its own rules rather than relying entirely on outside agents to do so.8

An imaginary noninstitutionalized international system would lack shared expectations and understandings. Coordination would be impossible even when common interests existed. Policy in a true sense would be unknown, and state interaction would have a random quality. In practice, all international systems of which we have knowledge contain, or quickly acquire, conventions that permit coordination of action and alignment of interpretations of the meaning of action.

Conventions, however, do not necessarily specify rules with any precision. When international regimes are negotiated on the basis of previous conventions, they typically expand and clarify the rules governing the issues concerned. The process by which international regimes develop is therefore a process of increasing institutionalization.

But regimes cannot adapt or transform themselves. In the absence of international organizations, international regimes are entirely the expressions of the interests of constituent states. International organizations, however, evolve partly in response to their interests as organizations and partly in response to the ideas and interests of their leaders; and in this evolution they may also change the nature of the regimes in which they are embedded. Regimes with very clear rules could be more institutionalized than organizations with little autonomy and vague rules; but insofar as rules do not change, the emergence of international organizations indicates an increasing level of institutionalization.

The distinction among conventions, regimes, and organizations is not as clear in actuality as this stylization might seem to imply. Negotiated agreements often combine explicit rules with a penumbra of conventional understandings, which may be more or less ambiguous. Perhaps without exception, international organizations are embedded within international regimes: much of what they do is to monitor, manage, and modify the operation of regimes. Organization and regime may be distinguishable analytically, but in practive they may seem almost coterminous.

The Significance of Institutions

International institutions are important for states' actions in part because they affect the incentives facing states, even if those states' fundamental interests are defined autonomously. International institutions make it possible for states to take actions that would otherwise be inconceivable—for example, turning to the United Nations Secretary-General to mediate between Iran and Iraq, or appealing to nonproliferation rules in justifying a refusal to send nuclear reactor equipment to Pakistan. They also affect the costs associated with alternatives that might have existed independently: rules embodied in U.S.-Soviet arms control treaties increase the costs (especially for future agreements) of building antiballistic missile systems, and GATT rules on import barriers increase the costs of imposing formal discriminatory quotas on imports. Evasion is often possible, as the innovation of "voluntary export restraints" indicates; but institutions do affect behavior, even if they do not always attain the desired objective.

Yet it would be misleading to limit the significance of institutions to their effects on incentives. Institutions may also affect the understandings that leaders of states have of the roles they should play and their assumptions about others' motivations and perceived self-interests. That is, international institutions have constitutive as well as regulative aspects: they help define how interests are defined and how actions are interpreted.9 Meanings are communicated by general conventions such those reflecting the principle of reciprocity and by more specific conventions, such as those that indicate what is meant in a diplomatic communiqué by a "full and frank exchange of views." Meanings are also embedded in the rules of international regimes, such as those of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which specify and implement the principle of reciprocity.10

The constitutive dimension of international institutions raises what Alexander Wendt (1987) has recently described as the "agent-structure problem." To what extent are the agents of international relations, principally states, "constituted" or "generated" by the international system? Wendt points out that it would be impossible to understand "capitalists" as agents without a concept of "capitalism," and he draws an analogy to international relations: "The causal powers of the state . . . are conferred upon it by the domestic a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Neoliberal Institutionalism: A Perspective on World Politics

- 2 A Personal Intellectual History

- Part One International Institutions and Practice

- Part Two Policy Choices and State Power

- Index