- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Czechoslovakia

About this book

Czechoslovakia only came into existence in 1918. But the history of the Czechs and Slovaks and the lands they inhabit goes back a long way. It is a history that is important for its own sake as well as for the legacy it gave the modern state and the understanding it brings to a study of present-day Czechoslovakia. It is also a history so rich in ma

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Book Two

Chapter 8

Establishing Czechoslovakia

Introduction

IN CZECHOSLOVAK TERMS, 1918 was a revolution. Before the war the Czechs and Slovaks were kindred peoples in separate sectors of a German and Magyar-ruled state. At the end they came together in an independent state. Their history was no longer that of separate, if related, national movements, but of a nation striving to express its identity and to maintain its independence. They were, of course, the same peoples, and they inherited problems and opportunities alike. But the framework within which they dealt with the one and made use of the other was quite different. They were a nation and they were independent; the history of Czechoslovakia as such had begun.

The world into which the new state was born was also radically different. The principle of national self-determination had triumphed. Its application barely extended beyond Europe and the Americas, and even there it was only imperfectly applied. Many of its ostensible champions paid mere lip-service to it. On the other hand, it was enshrined in the peace settlement and in the concept of a league of nations. It was legitimate for Czechoslovakia to be a nation and to fight to remain one.

Initially that was none too difficult since the distribution of power in the world had also changed drastically. Almost unbelievably, Austria-Hungary had collapsed, and despite fears and alarms the Habsburgs were never to return. The United States had thrown its power into the settlement of Europe’s affairs and, if it was shortly to withdraw, it was to leave Germany, would-be successor to Austria-Hungary in central Europe, apparently soundly defeated. Tsarist Russia, an uncertain ally to its fellow Slavs and long-standing opponent of nationalism, had also collapsed. If the Soviet Union was something of an unknown quantity, it appeared to support self-determination, and it was in any case likely to be burdened with problems of its own for some time to come. Britain had committed itself to European and international stability as never before. If there were doubts about its sincerity, there were none about the commitment of France to the new order in Europe. National self-determination had broken one French enemy, Austria-Hungary, and could contain another, Germany. It was a situation in which Czechoslovakia could entrench its independence.

To maintain it in the longer run was to prove much more difficult. The world remained dedicated to national self-determination, and Austria-Hungary found it impossible to recover. But the United States went off to be self-determined in its own peculiar isolationist way. Germany used the principle to assist its recovery as a power and to undermine Czechoslovakia’s existence. Britain and ultimately France grasped it as a shield for their unwillingness to fulfil their obligations towards Czechoslovakia. Russia employed it as an aid to defensive westwards expansion, against the interests of small nations. In 1938–39 Czechoslovakia lost its independence in a world that seemed to have reverted to the imperialism of pre-1914, or worse. The Second World War, however, accelerated the growth of nation-states. The principle of self-determination spread rapidly to Asia and Africa. When Czechoslovakia joined the League of Nations, it was one of forty-two members. When it joined the United Nations, it was one of fifty-one members. Yet the problem of maintaining even fairly basic independence was greater than ever before. The super-powers had arrived, complete with alliances and economic agreements and areas of influence. In 1948 Czechoslovakia slipped almost inevitably into the Russian sphere and virtually lost its independence. Came 1968 and there were a hundred and twenty-six members of the United Nations; but Czechoslovakia could not determine its domestic policy, let alone slide out of the Russian zone of Europe. Yet neither could it be destroyed. Its independence might be limited, like that of so many other small nations; but in 1968 the world was still a world of states, not of old-fashioned empires or modern federations.

As far as the Czechoslovaks were concerned, the international scene after 1918 was not all change. In particular, Czechoslovakia had not lost its strategic importance. The Czech Lands were still the fortress heart of Europe. They were valued highly by the French as a bastion in Germany’s rear and as a staging-post to Russia. They were then envied by Hitler for the reverse reason, as well as for their usefulness in any invasion of Poland or the Balkans. Later, both Stalin and Truman were aware of their crucial importance in the Cold War struggle over Germany. If Czechoslovakia’s military importance then declined in the nuclear age, its ideological importance continued to grow. Even more in 1968 than in 1948, it was obvious that, whatever way Czechoslovakia went, the rest of eastern Europe might follow. The Czechoslovaks had won their independence in 1918, but they could not escape their geographical heritage, no matter how hard they tried.

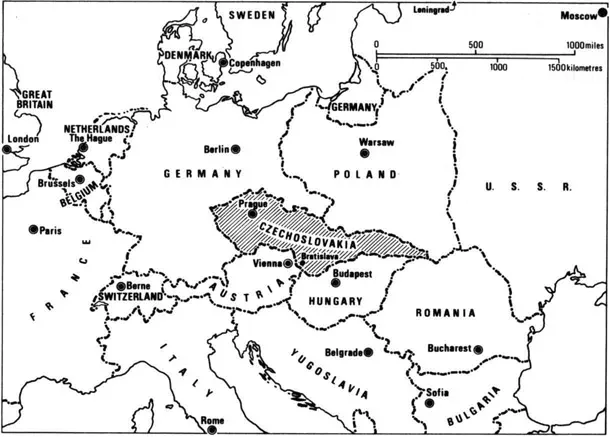

2 The Frontiers of Czechoslovakia before the Rise of Hitler

The history of the Czechs and Slovaks after 1918 is thus the history of the independent state of Czechoslovakia and of its struggle to survive in a world that blessed it in principle but was less kind to it in practice. There was another struggle, however, the struggle to become a nation in the full sense of the word. The two were not separate or disconnected. Hitler used the Sudeten German minority, just as Stalin used the Czechoslovak Communist Party, to cripple Czechoslovak independence. But the battle for nationhood existed in its own right. It was both ethnic and social.

The vagaries of history and the decisions of the peace conference gave Czechoslovakia an ethnically mixed population. In 1921 the Czechs and Slovaks comprised only 65.5 percent of it; Germans made up 23.5 percent, Hungarians 5.5 percent, Ruthenians 3.5 percent, Poles and some others the rest. Ethnically speaking, Czechoslovakia was a small reverse image of the Habsburg Empire. The painstaking attempt to find a modus vivendi with the Germans failed in 1938 and they were expelled in 1945. In the same year, the Ruthenians, and the area they lived in, were simply transferred to the Soviet Union. From then on, the Czechs and Slovaks numbered about 95 percent of the population and could claim to be the nation. Yet, from the outset the Czechs and Slovaks were not one nation; they were but kindred peoples thrown together by long suffering and common triumph. Tension was often high before 1945, and the fusion thereafter was somewhat artificial. The federal solution of 1968 recognised that the state would not fall apart, but the nation had some way to go before it was forged completely.

In the half-century between independence and 1968 a vast amount of energy was expended in trying to solve the ethnic problem. The framework was new, the problem old. This was also true of the struggle to unite the nation socially. Population growth continued, though there were two breaks, the one associated with the political disruption of 1918 and the other (and greater) with the national redistribution of 1945. This helped to maintain the pressure for economic development, particularly industrial. But 1918 added its own pressures. A new economy had to be created out of fragments surviving from Austria-Hungary, and it had to be productive enough to support independence. 1918 also increased the pressure to rise in the social scale; independence would have achieved little if it had not made openings for those below. All this, as well as the influence of socialist ideas rising within Czechoslovakia and gathering strength abroad, moved the new state towards reducing the differences between rich and poor, towards creating a single nation. The expulsion of the Sudetens in 1945 accelerated the process by enabling the Czechoslovaks to turn their attention from the national struggle to the social one. It only required the intervention of the Soviet Union to enforce social levelling after 1948, and to arouse the anger of a nation united against it in 1968, for the entire process to be as complete as perhaps it can be.

The Frontier

Czechoslovakia came into existence as a legal entity on 28 October 1918, but territorially it was still undefined. The Western governments had recognised the Czechoslovak people’s right to independence; their advisers had prepared memoranda on possible frontiers for the new state and had sifted memoranda from Czechoslovak spokesmen. But military exigencies, as well as political differences, had prevented the governments from reaching any kind of agreed position on what was by common consent a most difficult problem. In the circumstances it was easier to leave a settlement to the peace conference. The armistice with Austria-Hungary was based on the principle of national self-determination, but it made no attempt to map out what this would mean in practice.

For their part, the Czechoslovak leaders had definite ideas, and they had tried to get them across to the Western powers from the first moment when Masaryk made contact with Seton-Watson in Holland in October 1914. Before he was arrested, Kramář had been advocating a much more ambitious scheme than Masaryk’s, one that would have extended the frontier well into Germany by reverting to the position in the fourteenth century. However, it was the moderate view that prevailed. The area sought embraced the historic provinces of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia (apart from the sector with a Polish minority), and the Slovak-speaking part of northern Hungary. From an ethnic viewpoint this was not a national frontier. It pulled Germans, Magyars, and Poles into the new state along with Czechs and Slovaks. The fact was that an ethnic frontier was simply impossible. Centuries of population movement, and in particular of German migration, had produced too many mixed areas for any line, let alone a just one, to be drawn between Czechs and Germans or Slovaks and Magyars. This was another reason for Western indecision. But from 1914 onwards the Czechoslovak argument was never based on ethnic considerations alone.

Until 1914 there had been two strands in Czechoslovak thinking. State rights, the restoration of autonomy to the historic provinces of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, had originally been the political platform of the German aristocracy, but it had been taken over first by the Old Czechs and then by the Young. The newer parties, including Masaryk’s, had inclined rather to autonomy for national groups, a scheme that would have left part of the historic provinces under German autonomous government. It was this ethnic line of thinking that had supported autonomy for the Slovaks in close linkage with the Czechs. The two strands had never been wholly distinct, but the outbreak of war in 1914 brought them inextricably together. It was now a question of independence, not autonomy. The Czechoslovaks must be in a position to protect their new status. They must have strategically defensible frontiers; they must have an economically viable territory. In the west in particular, the new state must occupy the position formerly held by the independent kingdom.

Behind this reasoning there was a degree of emotionalism. The one-time flourishing kingdom had been suborned by German immigration and destroyed by Habsburg aggression. The clock should now be turned back, and a Czechoslovak state, albeit with a series of minorities, should be allowed to spread to the limit of the old frontier. There was even an element of revenge. The Germans had lorded it over the Czechs for three hundred years (the Magyars over the Slovaks for even longer); the boot should now be put on the other foot. Some of the statistics produced were downright inaccurate: the number of Germans in the new state was underestimated by almost a million. There was also a certain amount of double-think. The German minority was to be included with the new state for historical reasons; but in the face of similar arguments, Hungary was to lose its Slovak territory. Yet the same picture had its other side. The Czechoslovak argument was national, strategic, and economic, rather than crudely historical. The Germans’ statistics were at least equally faulty; they overestimated their strength in the new Czechoslovak state by more than a million. There was also a touch of genuine idealism in the Czechoslovak approach. The Germans of the historic provinces represented the outdated bureaucratic ineptitude of the Habsburgs and, more recently, the aggressive Pangermanism of imperial Germany. In contrast, the Czechoslovak national movement drew its inspiration from the democratic Western tradition and would therefore, or so it was argued, create a new kind of multinational community in the new state. There was even talk of adopting the Swiss model for its constitution, though this was more well-intentioned than realistic. Through every Czechoslovak argument, however, ran the need to create something viable. Austria-Hungary had been a failure; Germany could still be a menace; Czechoslovakia must be able to survive.

It worried the Czechoslovak leaders that no specific frontiers were mentioned in the Austro-Hungarian armistice. Their government had been recognised. The terms of recognition gave them a right to make representations to the peace conference then being organised in Paris. They were able to argue their point as well as any group, and they had several concessions they were perfectly willing to make. But recognition had come practically at the eleventh hour. Differences between the Western governments could rebound against them. Even recognition, let alone sympathy for their cause, could disappear as rapidly as it had come. Just after the end of the war the public mood in the West was as favourable to the Czechoslovak cause as the official attitude, but anything might happen in the longish spell before the conference was due to meet. The Austro-Germans and the Magyars were quick to argue their own case for national self-determination. The military situation in central Europe, which could determine the political, was very fluid. It was quite conceivable that the Austro-Germans and the Magyars, who were angry at their unexpected defeat, could turn it to their advantage. Nor could the Czechoslovaks expect help from the Soviet government, which did not wish to participate in the peace conference. It had also become embroiled with the Czechoslovak Legion still in Russia and was, if anything, hostile. Partly for that reason, too, there was no immediate prospect of getting the Legion transported to central Europe. In four years of war, the Czechoslovaks had advanced a long way; but they could certainly not afford to rest on their oars with the cessation of hostilities.

To begin with, the Czechoslovaks were united in their approach to the frontier question. Masaryk was the first President of the new state. Different shades of opinion were united under him, with Kramář as prime minister and Beneš as foreign minister. They acted together firmly. Masaryk was the symbol of good sense abroad and unity at home; Kramář kept passions cool; Beneš negotiated the actual settlement. The immediate problem was the lack of a military presence. The Western powers could not agree whether to send troops. The Austro-Germans and Magyars made hostile noises and appeared ready to fight. There was a real danger that Czechoslovak authority might be confined to a limited area of the Czech Lands. Most of the seasoned Czechoslovak troops were in Italy or France, or stretched across Siberia. But fresh troops were raised at home, and approval was obtained for assigning them officially to the French command so that they could operate as an Allied force in entering areas claimed by the Germans and Magyars. In the face of Austro-German protests and Anglo-American scruples it did not prove too easy to enter the German parts of the Czech Lands. Of tremendous assistance was the French desire for a powerful buffer-state; but ultimately of equal assistance was the Anglo-American fear of decomposition in the old Austria-Hungary if bolshevism were allowed to spread in the chaos of the post-war period and the hardship of a long cold winter. By the end of December 1918 Czechoslovak troops had occupied the Czech Lands in their entirety, on condition that this did not prejudice the final settlement. If anything, the occupation of Slovakia proved more difficult. In the moment of defeat, Hungary separated itself from Austria and established a moderate government in the hope of preserving the Hungarian kingdom from national self-determination. Czechoslovak soldiers trying to advance into Slovakia were repulsed; and some confusion in the armistice terms seemed likely to keep them out for good. It was again French self-interest that opened the way to eventual occupation. Indeed, it was almost solely a French success. Hodža, sent to Budapest on behalf of the government, was completely outmanoeuvred. The British government appears to have held aloof and the American to have played ostrich. The French government—not without Czechoslovak prompting, of course—acted unilaterally, and at the same time as sanctioning occupation of the whole of the Czech Lands, announced that Hungary had withdrawn from Slovakia—which, at French military dictation, it did. By the end of the year Czechoslovak troops were in possession. By dint of some negotiation and a series of faits accomplis, the Czechoslovaks made a reality of their territorial claims before the peace conference met.

In retrospect, the story is not altogether a pleasant one. But it was a hard world and had been so for a long time. If the Czechoslovaks had not moved, or the French had not moved for them, then the Czechoslovak state might have amounted to no more than a truncated part of the Czech Lands, probably without Slovakia. A major battle for the nation would have been lost, and the next one would really have been over before it had begun; the mini-Czech state would have been weak and defenceless, a very easy prey for its stronger neighbours. Nothing was taken that had not previously been asked for, and adjustments could still be made. The Czechoslovaks had had too long a history of policies stymied and concessions withdrawn to be willing to leave so much to the peace settlement. Possession was two-thirds of ownership; for once in their history they could argue their case from a position of real strength.

The peace conference met for the first time on 18 January 1919. Beneš and Kramář appeared before the Council of Ten, as the inner group were styled, on 5 February. The so-called Commission on Czechoslovak Affairs sat from 28 February to 12 March, on which date it presented its almost unanimous findings on the Czechoslovak frontier. There were still several stages for the appropriate treaties to go, but by and large the geographical shape of the new Czechoslovak state was settled. It was not nearly such plain sailing as the quick timetable might suggest. Kramář, who as prime minister was senior to Beneš and responsible for drawing up the papers, stretched the Czechoslovak claims beyond the frontiers of occupation. Success had gone to his head, as it had with others of his less elevated countrymen. The Commission would simply not accept his extravagant claims, and it took all Beneš’s moderating approach to undo the damage. That in itself raised problems, since Beneš’s willingness to make minor concessions opened the way to unreasonable demands. The American delegates raised more difficulties than anyone else. They were committed to self-determination but, like their master, Wilson, they were not very sure what it really meant. They also believed in viability, and ultimately came to much the same conclusions as everyone else. They did utter warnings about future problems, but in the end they reserved their position on only one point, insisting that Cheb ought to go to Germany. Strangely enough, this was also Beneš’s view, but it was the French who carried the others with them. Indeed the whole operation was more of a French success than of a Czechoslovak. The French were now thoroughly convinced of the need to buttress Czechoslovakia as a major ally in central Europe. They very quickly obtained support for Czechoslovak possession of the historic provinces as a whole, and although there was some tough arguing, most of it was concerned with points of detail—or with Slovakia. It was rather ironic that Slovakia, not possessing a historic frontier, raised more heat than the Czech Lands. Yet it was natural enough, since its frontier called essentially for an ethnic decision. This gave the Americans in particular an opportunity to discuss matters of principle that were barely susceptible of settlement. Perhaps surprisingly, it was in this area that the British delegates did most to promote a sense of reality by insisting on the Czechoslovak need for internal rail communications. In general it was the French who pushed, supported by the British, while Kramář and the Americans just about cancelled one another out; and behind them all was Beneš, young in years but old in experience, gently negotiating towards acceptance of the already existing occupation situation.

There were still some obstacles to be overcome. When the Commission’s report was presented to the three great political figures of the conference, it looked for a time as if Clemenceau would not get the French government’s way; Wilson and Lloyd George began arguing in favour of an ethnic frontier. But whereas Wilson was rather confused and Lloyd George could not formulate a clear alternative to the Commission’s plan, Clemenceau was clear-cut and single-minded in pursuit of viability. Face to face with reality, the ethnicists could not win. There were in any case other pressing problems to worry the Big Three. The Franco-German frontier still had to be agreed; and it was a big issue. There was a whole series of east European frontiers to be agreed. The civil war in Russia was at its height. To cap everything a bolshevik revolution in Hu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Note on the pronunciation of Czech and Slovak names

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- BOOK ONE

- BOOK TWO

- Reading List

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Czechoslovakia by Michael B Wallace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.