eBook - ePub

Combining Facts and Values in Environmental Impact Assessment

Theories and Techniques

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1988. This book has grown from a research workshop that began at the University of North Carolina under the direction of Maynard Hufschmidt. Professor Hufschmidt's long-held interest in the incorporation of environmental and other social values into benefit-cost analysis led to a research project entitled, "The Role of Environmental Indicators in Water Resource Planning and Policy Development, " funded by the U.S. Department of the Interior. That project brought together the authors of this volume for a two-year period during which the groundwork for this book was laid.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Combining Facts and Values in Environmental Impact Assessment by Eric L. Hyman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

The Evolution of Environmental Assessment

1.1 Characterization of Environmental Assessment

Environmental assessment consists of the prediction of future changes in environmental quality and the valuation of these changes. The purpose of environmental assessment is to provide decision makers with guidance for making informed tradeoffs among conflicting aspects of environmental quality and between environmental quality and other societal objectives. Our definition of environmental quality encompasses the functional and aesthetic attributes of natural systems that sustain and enrich human life.

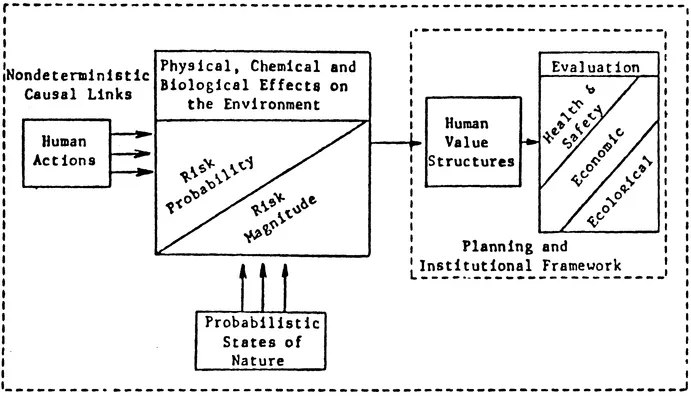

The environmental assessment process has an objective component and a subjective component (figure 1-1). The objective component deals with facts and falls within the domain of the natural and physical sciences. It produces predictions of the resulting biological and ecological effects of these changes on plants, animals, and people. The expected effects are actually probabilities because of the variability and uncertainty that are inherent in natural systems. Often, the effects of alternative actions or projects are compared under different scenarios for the selected technologies, planning and regulatory strategies, and induced market activities.

There are established principles to follow in assessing objective effects on ecosystems (Walker and Norton 1982). Baseline data and predictions of changes in natural systems that would otherwise occur in the absence of the human action are needed so that effects can be attributed to the action. Yet, sometimes too much effort has been devoted to collecting baseline data at the expense of the predictions of impacts (Beanlands and Duinker 1983).

The subjective component deals with values and falls within the planning and institutional framework. It involves comparing diverse effects to develop measures of the overall impact on environmental quality and weighing the environmental impact against impacts on other societal objectives. Other societal objectives that may be

Triple arrows indicate that the causal links are nondeterministic or subject to uncertainty. Figure 1-1 The process of environmental assessment (Adapted from Hyman, Moreau, and Stiftel 1984, p. 211). Reprinted by permission.

considered in government decision making are national economic efficiency; regional economic development; equity within and across generations; and various effects on the sociocultural, psychological, and political well-being of people.

The following example shows both components. Suppose that anticipated growth in an area's population and economic activity will increase discharge of organic matter into a nearby river. These discharges can be predicted as a function of the technology of waste generation and treatment. Models of transport and transformation processes or statistical analyses can be used to estimate how concentrations of the organics are likely to vary by location in the river. These concentrations could then be compared with baseline levels and water quality standards and criteria to predict the number and types of fish and other organisms harmed as well as the number of people exposed to contaminated drinking water supplies. After that, an analyst can identify the diverse values placed on these losses and the costs of preventing or cleaning up the pollution. The final judgment on how much should be spent on prevention or mitigation of impacts and who should bear the costs and benefits of these activities is up to the decision makers.

This view of the environmental assessment process is based on a rational model of planning and decision making. The rational model assumes that societal decisions are made in a systematic way that maximizes individual or social well-being, given limited resources and costly information (Banfield 1955; Janis and Mann 1977). In its most basic form, the rational model consists of a five-step process: (1) identifying a problem or opportunity, (2) setting objectives, (3) developing planning guides and criteria, (4) formulating alternatives, and (5) evaluating and selecting the preferred alternative. More sophisticated forms of the rational model allow for feedback because they recognize that the above steps are interdependent (Quade 1975).

The rational model approximates reality best when alternatives can be well defined and decisions made by a single administrative agency (Hufschmidt 1974). In reality, decision makers aim to produce satisfactory rather than optimal decisions (Simon 1975) and often proceed in disjointed, incremental steps (Lindblom 1959). The rational model has a serious conceptual difficulty in that it provides no guidance on how decision makers can choose which of the diverse values held by individuals and groups should be adopted. Also, changes in conditions may alter the rankings of objectives as well as the means of achieving them (Frohock 1979).

1.2 The Current Status of Environmental Assessment

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) was a reaction by the U.S. Congress to the prevailing public opinion that the conventional planning processes of the executive branch did not adequately account for environmental factors. NEPA requires U.S. federal agencies to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) for major federal actions that may significantly affect the quality of the human environment. Such actions include projects, investments, regulations, and legislative proposals. An EIS must report on

- Any adverse environmental effects which cannot be avoided should the proposal be implemented

- Alternatives to the proposed action

- The relationship between local short-term uses of man's environment and enhancement of long-term productivity

- Any irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources which would be involved in the proposed action (Section 192(2) (C)).

NEPA does not force federal agencies to select the alternative that is preferable on environmental grounds or even to use benefit-cost analysis to weigh tradeoffs between environmental quality and other societal objectives.

The first set of NEPA-implementation guidelines, issued by the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in 1973, had the status of recommendations rather than legally binding regulations. They provided little specific guidance on how to prepare an EIS. Instead, federal agencies were required to write their own regulations, and thus, over seventy different sets of regulations of varying quality were produced. As a result, the courts took over the task of sharpening the substantive requirements with the force of law to establish uniform standards for preparing environmental impact statements. These regulations outline a process rather than offering an approach, but they do attempt to focus the analysis on significant issues and avoid duplication of effort through a "scoping" step.

By late 1985, federal agencies in the United States had issued almost 23,500 environmental impact statements (M. Henderson 1985). Many states have also enacted "little NEPA" laws. Yet, the impact of this tremendous amount of costly activity is unclear. Most impact statements have been voluminous compendiums of largely irrelevant and under-analyzed data. The major reasons for this disappointing experience are the procedural rather than substantive focus of the law and the inadequacy of existing methods for environmental assessment with respect to the treatment of facts and values. The EIS process has had two positive contributions in the United States. It has encouraged agencies to screen out some projects with large, adverse, environmental impacts and has broadened opportunities for public scrutiny and participation in government decision making.

Since the U.N. Conference on the Human Environment at Stockholm in 1972, international interest in maintaining environmental quality has grown substantially. By 1980, over 50 developed and developing countries had instituted requirements for environmental impact statements, and 102 less developed countries now have government protection (EIA Worldletter 1983). One example of a major EIS in a less developed country is the one done for the Mahaweli River Development Program in Sri Lanka (Tippetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton 1980). The major multilateral development banks, U.N. project-implementing agencies, and some bilateral aid donors have also adopted environmental review procedures (Horberry 1983). Guidelines for environmental assessment have been prepared by the Organization of American States (1978) and the Mekong Secretariat (1982), among others.

The experience in less developed countries shows that environmental assessment procedures have promise, but have been of limited effectiveness to date (Hyman 1984; Lim 1984; Hufschmidt 1985). In addition to the problems encountered in the United States, less developed countries often face stringent constraints on budgets, available expertise, baseline data, and political feasibility.

1.3 The Development of Environmental Assessment Methods

Environmental assessment methods have evolved from work in five areas: (1) land-use planning tools; (2) benefit-cost analysis; (3) multiple-objective analysis? (4) checklists, matrices, and networks; and (5) modeling and simulation approaches. During the 1970s, the evolution of these methods accelerated resulting in generally greater sophistication. Representative examples of the methods mentioned below are discussed in detail in chapter 7.

1.3.1 Land–Use Planning Tools

Geologists, ecologists, landscape architects, and urban planners have developed various tools for land-use planning. Some of these tools focus solely on biophysical features while others include economic and social aspects as constraints on the selection of a site. Many factors affect the biophysical suitability of a site for particular land uses, including

- Climate--precipitation, temperature, wind, droughts, floods, storms, Eire risk, and air pollution potential

- Geomorphology and geology--slopes, stability, location and uses of surface water and groundwater, mass movements of earth, depth to bedrock, and unique features

- Soils--nutrients, structure, depth, and erodability

- Flora and fauna--biological diversity, ecosystem fragility, valuable species, pests and diseases

There, are two main types of land-use planning tools: land classification and land-suitability analysis.

Land classification approaches identify the best land uses for each type of site in terms of its biophysical features. These classifications may be made at various levels for different purposes. A macro-level classification is a broadbrush scanning of large land areas to establish national or regional priorities. A microlevel classification is a task for public or private sector land managers who have such mandates as economic production, watershed management, wildlife conservation, or security.

Table 1-1 lists a variety of land classification techniques. Remote sensing may be extremely useful in applying these techniques. These techniques have some limitations. Most are oriented toward a particular land use such as agriculture or forestry. They are less suited for determining appropriate management practices for existing land uses or for predicting the consequences of proposed changes in land use policies (Mueller-Dombois 1981). None of the techniques measure land productivity directly or identify the impacts of land use conversions. Moreover, these techniques may neglect gradual changes in biophysical factors that result in varying limitations on land uses (Lee 1981). Often, they are more useful in ecological studies than in helping decision makers answer land management questions (Cameron 1981).

Methods of land-suitability analysis focus on the constraints that could inhibit a particular land use. They are used for screening out sites that have unacceptable physical or spatial characteristics for that type of development. There are three types of land-suitability analysis: gestalt, mathematical combination, and logical combination methods (Hopkins 1977). Gestalt methods ask a team of experts to determine appropriate future land uses by viewing "the lay of the land." The experts look at such variables as slopes, vegetation, soils, and existing land uses (Hills 1961; Lewis 1963). Mathematical combination methods apply numerical measures to represent the site's degree of suitability for development. The results may be displayed on maps or map overlays (McHarg 1969) or numerical scores (International Planning Associates 1978).

Logical combination methods define site suitability through a hierarchy of factors or constraints. Some of these methods have been computerized, (Fabos, Green, and Joyner 1978) and different areas of a site can be represented through grid cells, polygons, or image processing (Steiner 1983).

Land-use planning tools for a biophysical assessment are important, but financial and economic analyses are needed to maximize the values obtained from the use of land

TABLE 1-1 Common land classification methods

| 1. | Australian Land System The Australian Land System (Christian and Stewart 1968) uses aerial photos to survey large areas for agricultural, forestry, and recreational potential. A site is defined as a uniform land form with common soil types and vegetation. A "land unit" is a collection of related sites with a particular land form. A "land system" is a group of associated land units, usually bounded by a geological or topographic feature. |

| 2. | Ecological Series Classification The Ecological Series Classification (Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg 1974) describes forest habitat types in bioclimatic terms: a plant community's soil, water and nutrient regimes; s... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Acronyms

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 THE EVOLUTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT

- 2 PITFALLS IN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT

- 3 INCORPORATING REPRESENTATIVE VALUES THROUGH PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

- 4 ESTIMATING THE MONETARY BENEFITS AND COSTS OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY

- 5 PERCEPTION AND EVALUATION OF SCENIC ENVIRONMENTS

- 6 ENERGY ANALYSIS: AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH?

- 7 A REVIEW AND ANALYSIS OF FOURTEEN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT METHODS

- 8 SAGE: A NEW PARTICIPANT-VALUE METHOD FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT

- REFERENCES

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- INDEX