- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The creation of jobs is critical in Third World countries where growing populations face unemployment or inadequate employment. Many have put forth theories and suggestions that address this problem, but there has been insufficient empirical analysis of the effects of specific policies on employment growth. The author examines macroeconomic theories of labour market behavior and labour force definitions and concepts, assessing how productive they are in formulating employment strategies for Colombia. The implications of a range of alternative policies for generating jobs, their effectiveness in reducing unemployment, and possible programs for the future are analyzed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alternatives To Unemployment And Underemployment by Michael Hopkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

An Overview of Major Theories of Unemployment1

1. Introduction

In this chapter an overview is given of the leading strands of thought that have attempted to explain, among other things, the economic causes of unemployment. Most theories do not centre on the causes of unemployment;2 rather they are mainly concerned with what causes, inter alia, accumulation, changes in the profit rate, inflation, growth, changes in wages. Clearly, these causes are interrelated and so the emphasis of theory on a number of problems at once is not altogether surprising. The main purpose of writing this chapter is to identify for the reader what the different theories say about the causes of unemployment and then link that discussion to an examination of the causes of unemployment in Colombia.

What theories to consider, and to what depth, has been an eclectic choice in the sense that those theories which have, according to the author, most to offer the analysis of contemporary unemployment problems in Colombia have been treated in more depth. Theories have been considered that apply both to developing and to developed countries because, while countries at different stages of development have different settings for their common problems, theory can transcend these boundaries to a limited extent. However, this should not imply that there is, or ever will be, a unique theory that can be applied everywhere. As Komai3 has remarked, there is no such thing as an optimal system containing the best possible rules. Planning an economic system is not like visiting a supermarket where on the shelves can be found the various components of the mechanism incorporating the advantageous qualities of all systems. “On one shelf there is the high degree of workshop organisation and discipline as in a [Federal] German or Swiss factory. On another there is full employment as it has been realised in Eastern Europe. On a third shelf is an equality of income and purpose such as found in Mao’s China. On a fourth is economic growth free of recession, on a fifth price stability, etc.” (Komai). Yet, given this caveat, a coherent body of theory that can be implemented in a democratic planning framework is attractive, and here I think more of Keynes and Marx than of Smith and Friedman.

In this chapter theories dealing with the labour market will be discussed in temporal order. I have arranged them into six main groups in order to preserve some common factors, namely classical theories (Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, Mill, Marx); neo-classical (Say, Marshall, Schumpeter, Pigou, Hayek, Wìcksell, Walras, Solow, Harrod, Domar); social reformers (Keynes, Lenin, Prebisch, Komai); latter-day development economists (Lewis, Fei, Ranis); monetarists (Friedman); and a relatively new and growing area, segmentation theorists (Carnoy, Harris, Todaro). In this list there are gaps and overlaps between the different schools. Many would say that there exist today, at the most, two main schools of theory: neo-classical and non-neo-classical. But this is an oversimplification, because there are theories or ideas from one school that can be applied in the other. At different times Keynes could have been considered a classical, neo-classical, Marxist or even monetarist scholar since there are strands of each school in his writings.

2. Classical Economists

These economists, working in the mid-nineteenth century, were greatly concerned with the interactions between labour, capital and land. Adam Smith in The wealth of nations, first published in 1776, was concerned with the principles of free competition and the “invisible hand” of the open market. Few economists would disagree with Smith that markets work when one important condition holds, namely that the actors in the market have equal weight in terms of size of firm, information, human and physical capital. However, this condition does not hold in the world today, nor is it likely to. Attempts to resolve this overriding qualification led to the growth of economics as a science. To act according to free market philosophy when inequalities exist, is therefore incorrect.

For Smith,4 the growth of the labour force was related, on the supply side, to population. In the long run he believed that population growth was regulated by the funds available for human sustenance. Consequently, the wage rate plays a crucial role in determining population size. The limiting wage was that which was neither sufficiently high to permit an increase in numbers, nor sufficiently low to force a shrinkage of the population base. Smith called this rate “the subsistence wage”, one which is consistent with a constant population. Smith thought that in a purely competitive market, if the wage rate fell temporarily below what was necessary to maintain labour demand and supply in balance, the pressure of demand would act to raise it Conversely, should wages be above the equilibrium level, then the excess supply resulting from too rapid a growth of population would soon lower the remuneration of labour. But what determines the demand for labour? In Smith’s words,5 “the demand for those who live by wages, it is evident, cannot increase but in proportion to the increase of the funds which are destined for the payment of wages. These funds are of two kinds: first the revenue which is over and above what is necessary for maintenance; and, secondly the stock which is over and above what is necessary for the employment of their masters.” This is the wage-fond doctrine. It relates the employment of labour to the size of the revolving fund destined for the maintenance of the labour force.

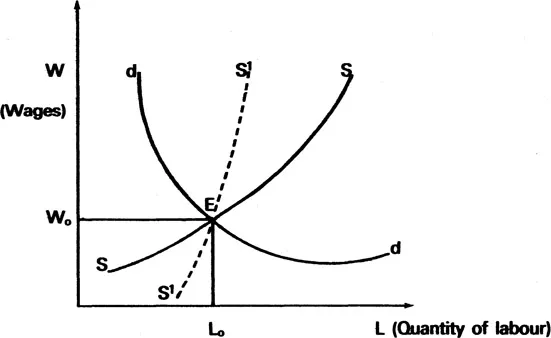

An illustration of Smith’s view, following Samuelson,6 is given in figure 1.

Figure 1. Demand and supply curves for labour

The demand and supply curves for labour intersect at full employment E, at a wage of Wo and a quantity of labour Lo, i.e. labour will offer itself either at an equilibrium wage level or, if there is excess demand for job in the system, workers will reduce the wage at which they offer themselves until equilibrium is reached. (The dotted line S1 S1 indicates a more inelastic labour supply function.)

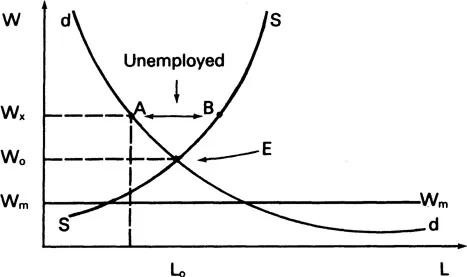

Figure 2. Unemployment and competitive wage cuts

Figure 27 illustrates how Malthus’ theory of population implies a constantly increasing supply of labour at subsistence level Wm at which people will just reproduce their numbers. Malthus’ theory fell down because he ignored the Keynesian demand effects of a growing population8 which would serve to push up incomes and the level of living above subsistence level.

Marx’s “reserve army of the unemployed” — as shown by AB — need not depress real wages from Wx to the mm minimum subsistence level. With perfect competition it can only depress wages from A to E. If labour supply became so abundant that SS intersected dd at mm, the wage would be at a minimum level, as in many underdeveloped regions. But institutional or legal changes can do little when marginal productivity is so low. That open unemployment has remained around the 10 per cent level in Colombia over the past 20 to 30 years suggests that these simplistic diagrams cannot easily be relied on there. This we discuss later in Chapters 2 (data on unemployment and wages) and 3 (segmentation of the labour market).

David Ricardo, as a forerunner of Marx, generally limited his studies to the distribution of the social product and, according to Hagen,9 established two main principles. One was that wages could only rise with rises in the accumulation of capital. The second principle was that the landowning class contributed a growing social weight whose power could be reduced only through free imports of agricultural products.

Ricardo’s production function, like Adam Smith’s, postulated the existence of three factors — land, capital and labour. In contrast to Smith’s function, however, Ricardo’s was subjected to diminishing marginal productivity,10 which stems from the fact that land is variable in quality and fixed in supply. As a result the marginal productivity, not only of land itself but also of capital and labour, declines as cultivation is increased. As many have remarked, a great weakness here is that Ricardo underrated the possibility of technological advance in agriculture. Ricardo’s notion of population and labour supply was similar to that of Smith, except that he believed that, because of capital accumulation, the market wage could rise above subsistence level. Yet, if labour supply exceeded labour demand, the market wage would fall to subsistence level so that labour demand would eventually equal supply.

Karl Marx’s main contribution to contemporary labour market analysis was a critique of the capitalism that he saw in nineteenth-century England. No other work, with the possible exception of Keynes’, can match Marx’s contribution to the economics debate. According to Furtado,11 the force of Marx’s vision was concentrated on two main things: firstly, identification of the fundamental relation of production of the capitalist mode, and secondly, determination of the major influences that develop the factors of production. Marx identified two main classes — capitalists and workers — and believed that the owners of capital would always seek to maximise profits (or surplus value as he called them) whilst paying workers a subsistence wage. These wages would allow labour to reproduce itself in order to maintain a reserve army of unemployed. Capitalists could, therefore, dictate both employment and wage levels.

To analyse capitalism, Marx introduced the labour theory of value. Simply put, this means that if 1 kg of rice were to be produced by 1 labourer in 1 week, and 2 kg of flour by 1 labourer in 1 week, then ½ kg of rice should have the same value as 1 kg of flour. Marx defined surplus value as the unpaid work of the workers. The total product of a nation, called the social product (P) was equal to the sum of constant capital [(C), depreciation, raw materials used in production, and energy inputs], variable capital [(V), paid salaries)] and surplus value (M), i.e.

Marx defined the rate of exploitation of the workers as as the index of organic capital needed to create new value, and as the profit rate. For accumulation, only surplus value could be transformed into capital (equivalent to the classical assumption that Investment = Savings). Marx did not indicate clearly what principles governed the distribution of surplus value between consumption and accumulation by the capitalist class. Considering that each capitalist simply struggled to increase surplus value, Marx did not much care about the conflicts within the capitalist class.

Marx predicted the demise of capitalism within the next 10 to 100 years, through a “crisis”. According to Marx12 this could come about because the capitalist mode of production produced a progressive relative decrease of variable capital as compared to constant capital leading to a progressive fall in the rate of profit. This would lead, from equation (1) above, to a reduction in surplus value and hence a reduction in the accumulation of capital. This process continues until capitalism collapses because of massive unemployment and social unrest. Capitalists could try and prevent this by ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- DEDICATION

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. An overview of major theories of unemployment

- 2. An examination and mapping of labour underutilisation in Colombia

- 3. Why is labour underutilised in Colombia?

- 4. Contemporary responses to the Colombian employment problem

- 5. Summary and conclusions

- Author index

- Subject index

- List of tables