- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Latin American Politics And Development, Fifth Edition

About this book

This book offers a region-wide overview of the patterns and processes of Latin American history, politics, society, and development. It provides a detailed country-by-country treatment and unique features of all Latin American countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Latin American Politics And Development, Fifth Edition by Howard J. Wiarda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part 2

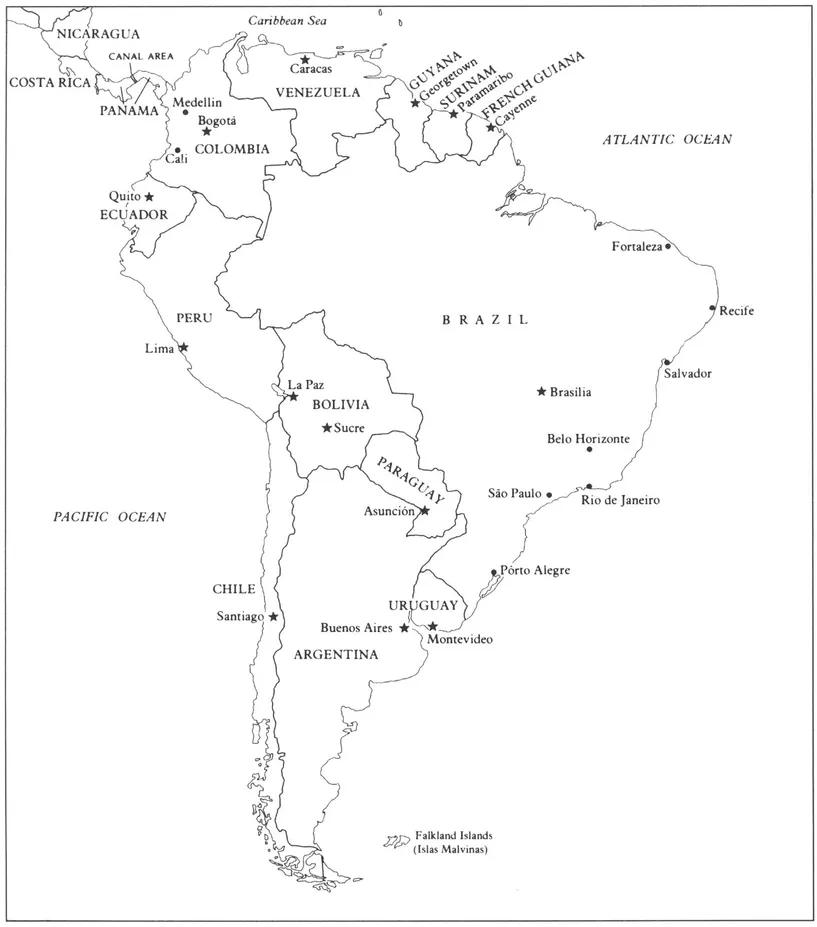

The Political Systems of South America

South America

6

Argentina: Intransigent's Paradise

Paul H. Lewis

Argentina is a paradox. On the one hand it is one of the world's wealthier nations. Its annual per capita income of about U.S. $9,700 puts it ahead of all the other Latin American countries except oil-rich Venezuela, and indeed ahead of some Western European nations. Moreover, Argentina has a much larger middle class than the other Latin American nations do. Most Argentines live in cities; are well-educated and highly skilled; have access to good medical facilities; are culturally sophisticated; and eat very well on a diet consisting of beef, fresh vegetables, and wine. Their capital, Buenos Aires, is one of the great cosmopolitan cities of the world. On the other hand, Argentina has been a political failure. In the seventy years from 1929 to 1999 there have been twenty-seven different governments in power at the national level, and twenty-four different presidents (some presidents having served more than once). Thus, the average administration lasted only about 2.5 years, as opposed to the constitutionally mandated six. Moreover, only eleven of those administrations came to power through election or legal succession. Five of them were ousted by the military. Of the other sixteen unconstitutional governments, fourteen were headed directly by military officers and three had civilian presidents closely controlled by the soldiers. They proved to be no more stable than the constitutional governments. Eight were ended by coups.

Congress was dissolved during twenty-three of those seventy years, in 1930-1932, 1943-1946, 1955-1958, 1962-1963, 1966-1973, and 1976-1983. The Argentine Supreme Court was also unable to uphold the rule of law. The military purged it in 1930 and packed it with sympathiz

Argentina

ers. Juan Perón, the populist leader, did the same after taking power in 1946. After he fell to a coup in 1955 the military purged the courts again, this time of Peronists. Another military regime, coming to power in 1966, abolished the Supreme Court altogether. It eventually was restored, but after the military seized the government in 1976 the Supreme Court remained intimidated and marginalized until democracy was restored in 1983. But even Argentine democrats have shown little respect for the judiciary. In 1990 President Carlos Menem increased the number of Supreme Court justices from five to nine and assured himself of a majority.

Obviously, Argentina's polity is less modern and developed than its society or economy. The Constitution is easily modified or ignored. Mediating institutions like Congress or the courts have been stunted in their development. All politics focuses on the presidency, and strong presidents usually get what they want. However, presidents are disposable, too. This endemic instability has resulted in economic stagnation. Both domestic and foreign investors shun the country as a bad risk, thus producing another paradox. Argentina's relatively high living standards are mainly a legacy of the past. In 1900 Argentina was one of the world's ten biggest trading nations, and one of the very largest holders of gold reserves. Since 1929, however, Argentina has fallen steadily behind its former competitors, losing markets, capital, and some of its best-trained people. In relative terms, it has been moving backwards while the rest of the world moves forward.

Failure, rather than inducing the Argentines to unify, has tended to polar ize them. Each group in society tends to blame the others and call for drastic solutions to reverse the downward slide. Instead of building up a stable constitutional order, without which no sustained development is possible, Argentina has become a paradise of ideological intransigents.

The Land

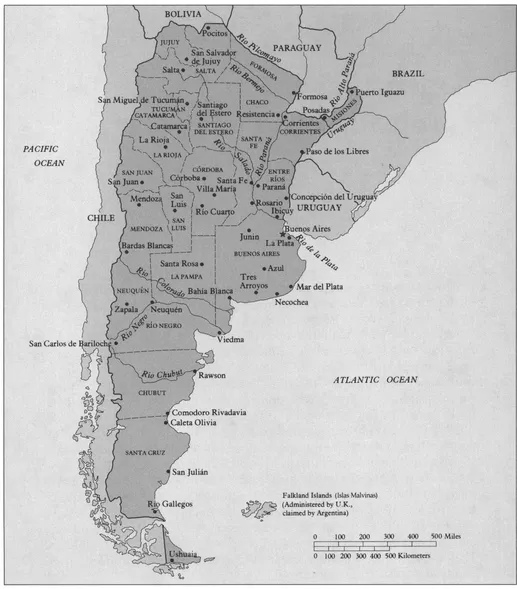

Argentina's size (1.1 million square miles, or 2.77 million square kilometers), makes it about four times the size of Texas. Located in the southernmost part of South America, in the area known as the Southern Cone, it faces the Atlantic Ocean to the east and has the Andean Mountains at its back. Its northern border, which it shares with Paraguay and Bolivia, is mostly tropical. Its south area, which includes Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, and (according to Argentine claims) a part of Antarctica, lies in the subpolar and polar zones.

Embracing so many climates as it does, Argentina is easily divided into many different regions, each with its own economic and social character. Most of the population and economic activity are found on the Pampa, a flat, open plain of rich soil, moderate rainfall, and temperate climate lying along the Atlantic coast and running into the country's midsection. This is where Argentina's principal exports—wheat, corn, and beef—are produced. It is also where Argentina's major cities and industries are located. Buenos Aires, the nation's federal capital and chief port, is an extensive metropolis of over twelve million people. It dominates the rest of the country politically, economically, financially, and culturally. The porteños, as the residents of Buenos Aires are known, consider themselves much superior to their fellow citizens in the provinces, and indeed to all of Argentina's neighbors. Whatever may be the accuracy of such a claim, it is certain that Buenos Aires does tend to draw in much of the talent of southern South America. In addition to Buenos Aires, the Pampa includes other large industrial hubs such as La Plata (approximately one million people), the capital of Buenos Aires Province; Córdoba (about two million), where much of the automobile industry is located; and Mar del Plata (about half a million), a popular beach resort on the Atlantic.

North of the Pampa lies another fertile plain, known as the Litoral because it lies between the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers. It is slightly warmer than the Pampa, but still produces beef and grain crops. Having been settled later in time than the Pampa, it exhibits more evidence of planned colonization, in the sense that there are fewer large estates and more medium sized farms. The city of Rosario (about two million), situated on the Parana River, is another major industrial center, with a number of important oil refineries.

Beyond the Litoral is the tropical Northeast, much of it a frontier region only recently settled. The population is a mixture of Paraguayans, with their unique Guaraní language and customs, and Europeans. Traditionally, the economic mainstay of this region was yerba maté, a bitter green tea, grown on large plantations, that is very popular in southern South America. More recently, however, cotton and citrus crops have been introduced.

Proceeding west from the Pampa the traveler encounters a range of low mountains, similar to the Appalachians, in the western part of Córdoba province. Beyond these is the desert, as the land falls increasingly under the rain shadow of the Andes Mountains. There are oases lying due west, however, in a region known as Cuyo. The main city here is Mendoza (approximately one million), and the principal economic activities are wine growing and the cultivation of olives. Much of this is done by small producers, many of them Italian immigrants.

North of Cuyo the Andes Mountains spread out to form the Bolivian altiplano. This is Argentina's most backward and impoverished region, cut off by the mountains from the Pacific coast and too far from the Atlantic. Much of the population is ethnically and culturally similar to Bolivians and lives on isolated farms in the mountain valleys. In the lowlands of Salta province, along the Bolivian border, there is some oil industry. Tiny Tucumán province, just south of Salta, was once the sugar-growing center of Argentina, but antiquated practices and the withdrawal of government subsidies caused this industry to go into a sharp decline, much of it moving to more modern plantations in Salta's lowlands.

Going south from the Pampa brings one to Patagonia, Argentina's largest, coldest, and emptiest region. Upper Patagonia is a transitional zone in which cooler-temperature fruit such as apples and pears can be grown. Farther down in Patagonia, however, the land becomes a bleak, windswept plateau, often buffeted by Antarctic storms. With the exception of oil fields located along the coast in Comodoro Rivadavia and against the Andes Mountains in Neuquén, this area's economic activity is limited to fishing, mining, and the raising of sheep for wool on enormous estancias, Argentina's sheep and cattle ranches. Mining consists of exploiting mainly low-grade coal and iron deposits.

The People

Argentina's population of just over thirty-five million is overwhelmingly urban (86 percent), with approximately one-third living in the greater Buenos Aires metropolitan area. It is also overwhelmingly of European descent, mainly Spaniards and Italians, and overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, at least nominally. Argentines are relatively healthy, although some deterioration in living standards is becoming evident. Infant mortality, at twenty-nine per one thousand live births, is about half that of Brazil, but twice as high as Chile. Similarly, life expectancy at birth (sixty-eight years for males, seventy-five for females) is much better than in Brazil, but not so good as in Chile. Literacy, at 95 percent, is almost the highest in Latin America (surpassed only by Uruguay).1

Argentina's ethnic mix (85 percent European, 12 percent mestizo, and 3 percent other) is a product of its unusual pattern of settlement. As a colony, it produced little wealth for the Spanish Crown and therefore remained sparsely settled. The Indian population was made up of small, nomadic, hostile tribes that were gradually driven off the Pampa by the settlers, down into Patagonia. By the end of the nineteenth century they were practically eliminated. At the same time, Argentina's cattle-raising culture required little importation of African slaves to work the estancias. In the last two decades of the nineteenth century there was an enormous influx of European immigrants, drawn by the attraction of vast tracts of cheap land, that significantly reconstituted the population. Today, Italian, French, German, English, Irish, Slavic, Jewish, and Arabic last names are common, as are Spanish.

The social structure, based on what can be gleaned from census data, reveals a basically middle-class society, one that is in crisis.2 The upper classes consist of two kinds of elites. First is the traditional large rancher/farmer estanciero elite. Although very wealthy, this is by no means a closed aristocracy. Many successful immigrants joined it during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Alongside it, and overlapping with it, is the more modern group of large bankers, merchants, and industrialists. The two elites mingle socially in the highly prestigious Jockey Club and tend to congregate in the same part of Buenos Aires, the fashionable Barrio Norte.

As in other complex societies, the middle classes range from a very well-to-do upper stratum that is positioned just below the elites to a petit bourgeoisie consisting of small farmers and businesspeople, white-collar professionals, and lower-level bureaucrats. Top military officers, government officials, Catholic clergy, lawyers, doctors, and managers of corporations form the upper middle class. Sometimes their control of the government may make some of them as powerful as the elites. Taken together, these middle classes may constitute over 40 percent of the economically active population.

The working classes also present a complex picture. At the upper levels are the white-collar workers (empleados) and the skilled laborers (obreros calificados). Skilled laborers often make more money than white-collar workers, but they lack the latters' social status. Empleados go to work in a coat and tie, and although they may own only one of each, they do not get their hands dirty. Obreros do sweaty work. Most working-class parents dream of getting their children enough education to move them up the social scale from the obrero to the empleado category, if indeed not into the lower middle class. Below these two groups are the semi- and unskilled urban workers, and below them are the unskilled rural peóns. Alongside of all these categories is yet another, shadowy part of the working classes: the so-called informal labor force, or cuentapropistas. These are unregistered workers who work, part-time or full-time, in the underground economy. In the last fifteen years of the twentieth century their numbers grew very rapidly, for reasons we discuss in the section on the economy, until it is now estimated that they may constitute nearly half of all workers in the country. The working classes, taken as a whole, probably make up slightly more than half of the economically active population.

The Economy

Argentina has a sophisticated economy based on plentiful natural resources, especially oil, a highly skilled labor force, an efficient, export-oriented agricultural sector, and a great variety of industries. Its estimated GDP in 1997 was just under U.S. $350 billion, far larger than that of any of its neighbors except Brazil. Its exports, consisting mainly of wheat, corn, beef, and oilseeds, amounted to over U.S. $26 billion. Imports, mostly machinery, equipment, and chemicals, amounted to just over U.S. $30 billion. Argentina's chief trading partners are Brazil, the United States, and Italy. In 1991 it joined Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay to form a regional trading bloc called MERCOSUR, which has proved to be an important boost to foreign trade. Economic growth during the 1990s has averaged between 6 and 8 percent a year, following a period in the 1980s of economic contraction and hyperinflation. Unfortunately, that period also left Argentina saddled with a huge foreign debt of around U.S. $120 billion. In addition, the turmoil in international capital markets following the Mexican, East Asian, and Russian financial crises has recently spread its shock waves to South America. Early in 1999 Brazil's economy began to go into recession, which eventually led to a devaluation of its currency. As the largest participant in MERCOSUR, its troubles inevitably affected its other partners. By late 1999, Argentina's economy was in recession as well.

The Argentine economy has a long history of "stagflation": a combination of stagnant growth and runaway inflation. The causes were structural and arose mainly from excessive government intervention in the economy. Populist administrations, beginning in the 1940s, based their electoral support on a combination of heavy social spending, trade protectionism, and ubiquitous economic regulation. Such an inward-oriented, "hothouse" economy was designed to guarantee high living standards for labor and to subsidize a large number of small, labor-intensive businesses that would provide plenty of jobs.

Traditionally, Argentina's economy was characterized by the dominance of large estancias in the countryside and small businesses in the towns and cities. Naturally, there were many exceptions to this general rule. Small and medium-sized farms and ranches produced profitably for the market, and there were even well-off tenant farmers. In certain industries, such as automobiles, pharmaceuticals, and rubber—any large enterprise requiring heavy capital inputs and advanced technology—big foreign companies dominated. The state was in control of "basic" or militarily strategic industries (energy, transportation, mining, oil, armaments, utilities). Often that meant the armed forces' direct ownership and management. The domestic private sector tended to concentrate on manufacturing light, nondurable consumer goods, such as food products, textiles, home furnishings, and small appliances. In addition, domestic private capital controlled most wholesale and retail commerce, as well as the service sector. With a few notable exceptions these locally owned private companies were small, employing fewer than ten people on the average. Many simply worked with their own, unpaid family members. In short, Argentina had an urban economy of mainly small capitalists, a "shopkeeper society."

This society began showing signs of breaking down in the 1960s. Argentine industry was inefficient, and its products were therefore both costly and, often, shoddy. Protected by tariffs and manipulated exchange rates, however, it had a captive market to exploit. Because most people lived in the cities and depended, directly or indirectly, on this industry, politicians hesitated to challenge it. The money to support public services came mainly from sales taxes, tariffs on foreign goods, and tariffs levied on Argentina's agricultural exports. The tariffs were greatly resented by the farmers and ranchers, but because they were only a minority of the population they were unable to change the policy. Nonetheless, these added costs were pricing Argentine beef and grains out of world markets, and as they did so the government's treasury began running low on foreign exchange.

By the 1980s Argentina was in a real crisis: deeply in debt, with banks and businesses failing, agriculture stagnant, and capital fleeing the country. Population trends added to the crisis. Like many other socially advanced countries, Argentina's birthrate had fallen greatly, to a little over 1 percent—not enough to replenish itself. Young people with skills were leaving for Europe or the United States while the elderly and retired were becoming an increasingly large portion of the population. All in all, the economically active portion of the public had fallen from 54 percent in 1960 to only 50 percent in 1990. A slight increase of women in the workforce helped to alleviate the situation somewhat, but with the growing recession and unemployment there was little incentive to seek regular work. On the other hand, the underground economy, where people worked for below minimum wages, evaded social security payments and payroll taxes, and flouted most other labor laws, grew rapidly. By the end of the 1990s it was believed to account for at least 60 percent of all economic activity, although no records exist to prove that assertion...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Acronyms

- Preface to the Fifth Edition

- I The Latin American Tradition and Process of Development

- II The Political Systems of South America

- III The Political Systems of Central and Middle America and the Caribbean

- IV Conclusion: Latin America and the Future

- Contributors

- Index