Computers in Education and Training

The use of computers in education and training has been greatly influenced by the history of their introduction into universities, colleges and industry, and by their use in applications other than education and training. Many of the earliest recognisable computers were developed and operated in universities on both sides of the Atlantic. Since those early days, the computer has grown in importance as a research tool so that now it would be unthinkable, in many subject areas, to carry out research work without access to a computer. Next, the effective, large-scale use of computers requires a cadre of trained staff to design and support computing systems and to help potential users who may not be skilled programmers. Teaching people about computers uses a substantial amount of computer time and, traditionally, research and teaching computing together account for most of the computing activities in higher education. At secondary level, where the research aspect is absent, computer education is dominant.

More recently, first in North America and then in Europe and elsewhere, teachers have realised that the power of the computer as a machine for storing, organising and processing information can be applied to teaching and learning. The computer may be used as a classroom resource, as a calculator, as a model of some real-life situation or as a means of producing animated visual aids. Alternatively it may be used in the background to help with the classroom management, keeping records of the students’ performance and carrying out other supportive functions.

In industry and commerce, the original reasons for installing computers were to support the every-day processes of the organisations; to carry out the calculations for payroll and invoicing, to process stock control information, to model the financial behaviour of the company and its environment, to control production lines and processes, and recently for more sophisticated applications such as airline reservation and operating systems. As teachers came to realise that computers could be used to support their teaching, so their colleagues in industrial training saw that the computers already in their organisations could be used to help in the training process.

Whether in education or training, teachers are faced with many and varied problems relating to their teaching and their students’ learning. Highly structured courses to meet the particular needs of individual students pose problems of instruction; modular course structures with more sophisticated assessment methods pose problems of student management; student centred courses to meet the particular needs of individual students pose problems of resource management; necessary practical experience may be time-consuming, expensive, or impossibly dangerous. Educational technology, in its widest sense, provides teachers with methods and tools which, properly applied, can alleviate some of these problems. The computer is one of these tools.

Education and Training Systems

Education and training involve complex systems which concern students, teachers and parents, resources such as schools and colleges, educational or training administrators, society and industry. This system is subject to pressures from a number of sources. In particular, three pressures, political, technological and social, can be seen as exerting considerable influence on it. These pressures are discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

In discussing the use of computing in all levels of education and in training, we must recognise that there are both significant differences between the two, and also common problem areas to which this technology may bring common solutions. These distinctions are perceived in different ways, by the practitioners who think in terms of outcomes, and by the educational or training technologists who think of the processes needed to achieve those outcomes.

One difference which is seen as significant by many teachers and instructors is that, while the main aim of the educational process is to benefit the student, in training it is the organisation that hopes to benefit by acquiring a more skilled person. The managers of educational and training systems have different expectations of their students’ success. The aim of the training process is to ensure that as many as possible of the students achieve all the course objectives and hence complete the training successfully. Most education systems, by accident or design, operate by a process of periodic culling, so that only the most successful students at the end of each stage may pass on to the next.

The process of education tends to focus on the student as someone to be guided through his learning and encouraged to widen his aspirations so that he can fulfil his potential in society. Education is perceived by its participants as a democratic process while training, in contrast, is usually more prescriptive. Training tends to concentrate on the student’s learning of the subject matter so that he acquires the necessary abilities and skill to carry out his role in the organisation. Clearly this is an oversimplification, because many training courses encourage students to extend their learning beyond mastery of the specified objectives, while much of education, particularly at the primary and secondary level, is concerned with the teaching of basic skills, such as arithmetic, and thus by the above definition is really training.

This difference in approach is also seen in the methods which are used to assess the students’ performance and progress. Training commonly uses criterion-referenced testing† which seeks to establish whether the student has achieved specified objectives. Assessment in education has also a qualitative flavour, and examines not only whether the objectives have been mastered, but also the degree of excellence achieved and how well each student has performed by comparison with his peers.

There are also considerable differences between the aims and processes of education at different levels. The shift in emphasis away from skills training to more abstract forms of knowledge in secondary and higher education is one obvious difference. A less apparent distinction is the change in the locus of control of learning as the student matures and moves from secondary to higher education. For the first part of his formal education, the student expects to be told what he must do in order to learn. Later, it may be desirable to wean him from this dependence on his mentor so that he can learn to learn by himself and, hence, continue to learn effectively after the end of his formal education.

Behind these different teaching and learning methods and objectives lie the common problem areas listed earlier: problems of individualising instruction to meet the particular needs of particular students; problems of managing students and resources; problems of providing particular learning experiences. For these problems computer assisted and computer managed learning offer some possible solutions — but have some limitations too.

Students and Information

The milieu of educational computing abounds with Lewis Carroll-like phrases which authors use to mean just what they want them to mean, nothing more and nothing less. The literature is confused with near synonyms such as computer aided instruction and computer aided learning† which are sometimes used interchangeably, but for some authors have subtle differences of meaning. Certainly there is a difference between the processes of learning and instruction; instruction is not a necessary condition, and is seldom a sufficient condition, for learning. The difference between computer assisted learning (or CAL)† and computer managed learning† (or CML) is more significant but difficult to define. Traditionally, the distinction has been that in computer assisted learning the learning material is presented to the student through the computer, while in computer managed learning the computer is used to direct the student from one part of the course to another and the learning materials themselves are not kept in the machine. So in CAL the student receives some detailed tuition from the computer whereas with CML he and his tutor get information about his performance and progress. However, many CAL systems also carry out some management functions. Similarly, some CML systems present tutorial information which would usually be associated with computer assisted learning. The difference between the two is therefore somewhat blurred.

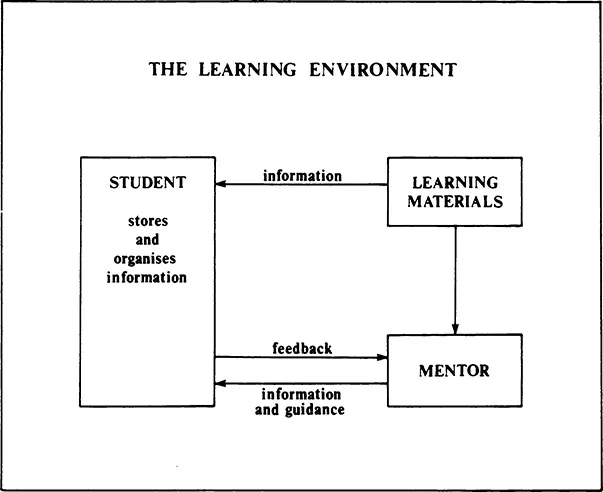

In a simplistic view of the learning process, the student acquires knowledge by receiving information from his surroundings and organising it so that he can then retrieve specific items, make generalisations and extrapolations. The speed, and perhaps the quality, of some learning may be improved if the student works with structured learning materials and is given some individual guidance by his mentor on his selection of a route through the modules. This implies that the student will supply information about his progress, problems and preferences. Hence there is a two-way flow of information with facts and guidance coming from the environment to the student, and feedback coming from the student. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Clearly this is but a crude and oversimplified model of the very complex processes which constitute learning; processes which we do not fully comprehend. It can be argued that until we have developed a better understanding of the learning process it is difficult to advance our use of educational technology. Perhaps — but then there are many teachers who are able to help their students to learn although they too lack a clear and complete theory of learning and it seems reasonable that we should proceed cautiously in advance of the theory.

This pragmatic view provides a convenient description of the various types of educational computing. The computer can be seen as a mediator of the two-way flow of information between the student and his learning environment. We have seen that there are various kinds of

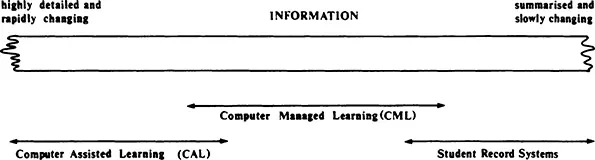

information, facts, feedback and guidance. There are also quantitative and qualitative differences in the information, depending on the scale at which the learning is examined. At the micro level, for example when the student is working in a small seminar group or is reading a book, the information is highly detailed and changes very rapidly. It is difficult to record and store all the information which is passed around during a lively discussion seminar, yet this is only a small part of each student’s learning activities during a course which lasts for several weeks, months or years. In the longer term, this level of detail is unnecessary and a summary of the flow is more relevant. So there is another scale at which the learning process can be viewed, where the information is rather less detailed and changes less rapidly. This might be at the level where the student’s activities are seen in terms of modules which take perhaps two or three hours to complete. Progressing further, this information can again be summarised to provide details of the learning process on a timescale which spans months, terms or years. Again there is less detail and a slower rate of change of information. This range of information detail and change is shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.1: The Student in His Learning Environment

We should remember that the basic information considered in the model is the same throughout the range; it is the level of detail that is changing. At each stage the information is summarised and so reduced in quantity before being passed onto the next stage. So at the detailed end of the range there is a vast amount of information relating to each of the courses or course fragments which the student is using. As the information is summarised, individual fragments are combined to build a more complete picture of his studies. Deliberately, there are no boundaries shown between the separate stages because no real boundaries exist — each stage merges into the next. In considering the learning process, the student and his tutor will use an appropriate level of detail which will depend on the individual student and his course.

Figure 1.2: The Spectrum of Educational Information

The different applications of computers to the learning process can now be described in terms of the way in which they mediate in the flow of information and of the levels of detail with which they are concerned. Thus, Computer Assisted Learning (CAL)† systems are involved with rapidly changing, highly detailed information and appear on the left hand side of the range. Computer Managed Learning (CML)† systems operate with less detailed information towards the middle of the range. Student record† systems appear on the right hand side and are concerned only with highly summarised accounts of the students’ activities and results. These three descriptions are used as working definitions in this book. The term educational computing is used to cover the entire spectrum and also to embrace some other applications, such as computer assisted media production, which do not conveniently fit into the framework.

Lest it should seem that the definition of these terms is unduly belaboured, we should note that the confusion in the terminology of different authors has been the source of many misunderstandings and misconceptions by their readers. Some authors use these same names with small changes in emphasis, or different names with essentially the same meanings. Thus, particularly in North America and continental Europe, the terms ‘computer assisted instruction’† and ‘computer aided instruction’ (CAI) are used to describe CAL. In the UK however, CAI can imply an application in which the computer is used to administer drill and practice examples or programmed instruction; CAL is, in some way, a more sophisticated use of the computer. Elsewhere in the literature, CAL is taken to encompass the whole of the educational computing.† The descriptions ‘computer based learning’† and ‘computer based education’† (CBL and CBE) are also found as alternatives to educational computing.

Justifications

The introduction of computer assisted and computer managed learning in different institutions at different times may be ascribed to a variety of reasons, some of which are altruistic, some more selfish. Three objectives are often advanced in support of the innovation. It is said that CAL will provide:

- — savings in costs and resources,

- — more effective education or training,

- — intellectual challenge.

Firstly, it may be claimed that the new techniques will save time or effort, or both, and hence will either save the institution money, or enable the available staff to teach or train more students. Secondly, other things remaining equal, the same staff with the assistance of the computer can improve the quality of their teaching and their students’ learning. A third reason is that the innovation will provide an intellectual challenge to the teachers with possibilities for evaluating courses more thoroughly and providing opportunities for a critical appraisal of their students’ learning. A final incentive, infrequently expressed, is that CAL and CML are stimulating and charismatic; participants in this new area acquire an enhanced professional reputation. While the novelty of most innovations holds considerable appeal, this effect is particularly apparent where computers are concerned. Many people find programming and the mechanics of computing irresistibly attractive; some may even get addicted, as if to a drug, and exhibit withdrawal symptoms if they are separated from their computer. This may present a humorous picture, but it does pose a severe problem because the enthusiast’s interest in the computer may obscure his judgement of its worth in a particular application. As we will see later, there is no good reason why a teacher must learn to write computer programs in order to use CAL. We should beware of forgetting our educational aims in the computing fervour.

As with many other educational innovations, although...