- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Comparative Political Finance Among The Democracies

About this book

This book is an in-depth exploration of political finances in and among mature and developing democracies of the world of politics in most continents: Japan and South Korea in Asia; Brazil in South America; Mexico and the United States in North America; and Italy, Germany, and Spain in Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Comparative Political Finance Among The Democracies by Herbert E. Alexander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

British Party Funding, 1983-1988

Following its heavy defeat in the 1983 general election, the British Labor party, under the leadership of Neil Kinnock, mounted a strong challenge to the Conservative Central Office regarding organization and fund-raising. The major unions, despite loss of members, continued to increase their financial support to the Labor party. Conversely, the Conservatives faced financial problems until 1986, when the Conservative Central Office sharply improved its fund-raising performance and increased its seriously eroded lead over Labor’s Head Office. In addition, the Alliance parties failed to build on their political success in the 1983 general election. The Alliance’s financial failure before and during the 1987 general election was symptomatic of the internal political difficulties that were to lead to the divorce between the Liberal and the Social Democratic parties and to the decline of the new center parties that replaced them.

Conservative Party Finances

The years between 1978 and 1986 were a rocky period for Conservative party fund raising. The Central Office was admittedly successful in the 1983-1984 election year when it raised £9.4 million, which was more than sufficient to cover the national organization’s routine costs and campaign spending. However, apart from that year, the Central Office was in almost constant deficit. From 1978-1986, Conservative Central spending was 12 percent greater than income,1 while Labor’s national income continued to catch up. The poor state of the Conservative finances contrasted with the party’s strong electoral performance. Beginning in 1986, Conservative Central income improved considerably and the upward trend in donations continued after Thatcher’s third election victory in June 1987.

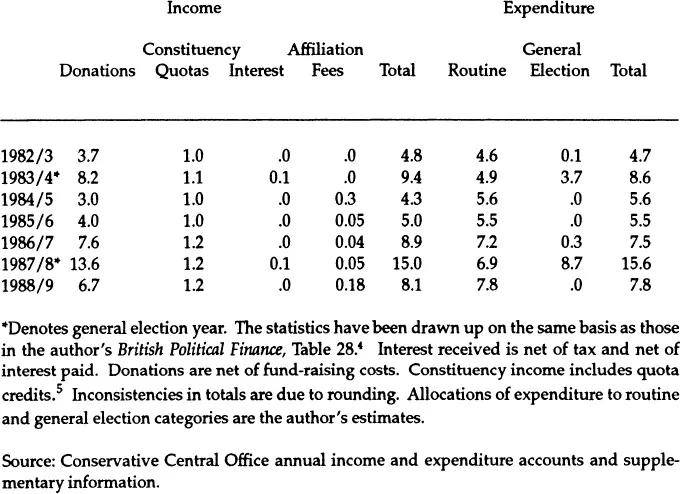

In 1987, Conservative Central Office campaign spending, as described below, was the third highest in the party’s history. It is, nevertheless, significant that estimated routine spending in 1983-1987 was, in real terms, nearly 10 percent lower than in the 1979-1983 cycle. The contraction in routine spending in 1983-1987 probably resulted from the party treasurer’s policy at that time of concentrating resources on general election spending rather than on the maintenance of the headquarters between elections (See Table I).2 In the parliamentary cycle 1983-1987, spending in the 1987 campaign accounted for some 28 percent of total central spending (routine and campaign), compared with 15 percent in the previous cycle.

Table 1 Conservative Central Income and Expenditure 1982-1989 (£m)

Statistics of Conservative spending in the 1987 general election supplied by the Conservative Central Office reveal that the party headquarters (including the area offices) spent a total of £9,028,000, in real terms nearly doubling the £3.8 million spent in the 1983 campaign.3 The main items of spending were press advertising (£4,523,000) and leaflets and posters (£1,834,000). Other major spending categories were staff and administration costs, £818,000; party publications, £714,000; leader’s tour and meetings, £417,000; production costs of party political broadcasts, £466,000; opinion research, £219,000; and grants to constituencies, £137,000. The figures may not be wholly comparable to those for 1983 since some expenditures during the run-up to the campaign, categorized in 1983 as routine, seem to have been included in 1987 as campaign items.

Central Conservative spending in the 1987 general election was the highest in real terms since 1964, amounting to £9.9 million at June 1987 values. Whereas, in 1964, a high proportion of expenditures was incurred during the two-year run-up to the campaign, most election spending in 1987 was concentrated into the month between the announcement of the election date and the poll. Indeed, the burst of spending by the Conservative Central Office on press advertising during the week before the vote probably constituted the heaviest short-term central campaign spending in British political history.

The Conservative Central Office, like the other central party organizations, does not issue a list of the corporate or individual donations it receives. Therefore, it is not possible to assess the proportion of the income listed as “donations,” which came from companies, large gifts by individuals, and relatively small payments from individuals in response to direct mail appeals. Two general propositions can be made. First, direct mail fund-raising was still relatively undeveloped at the time of the general election of 1987. It was only at a late stage in the parliamentary cycle that the Central Office became active in this new method. The profits of direct mail seem to have accounted for no more than 5 percent of the party’s central income in the election year 1987-1988, which was less than the proceeds of the Social Democratic Parties’ efforts.

Second, corporate donations appear to have accounted for a considerably smaller proportion, and individual contributions for a greater proportion, of central income than before. In its fund-raising methods, the Central Office would seem to have been trying to exploit both the old-fashioned method of a personal approach to wealthy individuals and, to a much lesser extent, modem methods of direct mail.

Constituency payments of the central party organization made up a smaller proportion of Central Office income than in recent parliamentary cycles (barely 12 percent of total income in 1983-1987, compared with 17 percent in 1979-1983, and 20 percent in 1974-1979). During the 1980s, constituency quota payments were smaller in real terms than in the 1970s. This may reflect a decrease in the membership and activity of local Conservative parties during the 1980s.

In the 1983-1987 parliamentary cycle, routine Central Office income was marginally higher in real terms (11 percent) than in 1979-1983.6 If overall routine and campaign income is included, the rise in real terms was 23 percent. Over the longer term, income in 1983-1987 was slightly higher (about 10 percent) than in parliamentary cycles between 1951 and 1964.

Labor Party Finances

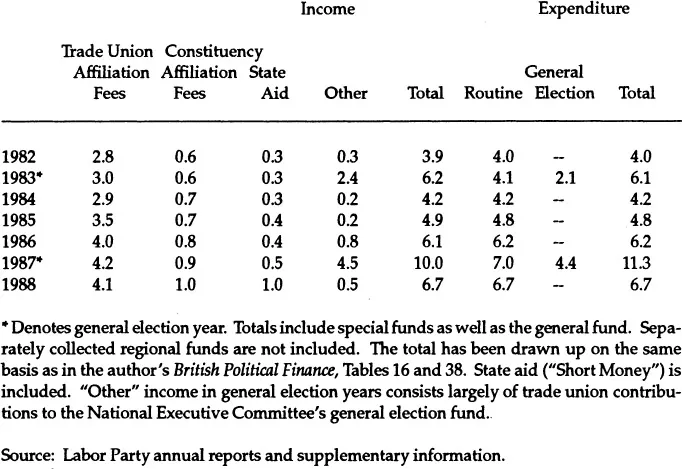

Like the Conservatives, Labor increased its central income during 1983-1987. Routine income averaged £5.4 million (at June 1987 prices), 15 percent higher in real terms than in 1979-1983. Overall income (routine and campaign) was more than a fifth higher than in 1979-1983 and nearly 50 percent higher than in 1974-1979.

The improvement in Labor’s Head Office finances resulted mainly from the increase in routine affiliation payments by trade unions. The affiliation payments rose from £2.9 million in 1984 to £4.2 million in 1987. Prior to this, these payments totaled £2.0 million in 1980, and £272,000 in 1969. Taking into account the rate of inflation, the value of these payments in 1987 was nearly two and a half times greater than in 1969.

The 1980s saw a significant improvement in affiliation payments to the Head Office by constituency Labor parties. Constituency payments to the Head Office reached £897,000 in 1987, compared with £570,000 in £378,000 in 1980, and a mere £143,000 in 1978.

In addition, Labor’s direct mail fund-raising activities, established in 1984, constituted another useful source of income by 1987, though less was raised by this method than by the Conservatives or by the SDP. In 1987, direct mail fund-raising produced an income (net of costs) of £573,000 of which £252,000 was for the general election fund. (See Table 2).

Besides increasing its routine income and expenditure, Labor’s Head Office spending in the 1987 general election was at a level only equaled in real terms, in 1964. According to the 1988 annual report of the National Executive Committee, Labor’s Head Office campaign expenditures totaled £4,210,000. In addition, according to information supplied by the Home Office, Trade Unions for Labor (TUFL)7 contributed £170,000 toward the costs of the leader’s tour. If the separate funds of regional Labor parties are included, the total rises to about £4.7 million. The central Labor budget was two-thirds greater in real terms than in the 1983 elections.

The main items of Head Office campaign spending (according to revised information supplied by the Labor’s Head Office) were: advertising, £2,114,000 (including national press advertisements, £1,356,000; regional press advertisements, £363,000; cinema advertisements, £86,000 and posters, £309,000); campaign rallies and leader’s tour, £67,000 (net of the press conferences), £139,000; grants to constituency campaigns, £423,000; cost of literature (net of proceeds from sales), £263,000; opinion research, £168,000; and administration, organization, staff, and other costs, £890,000. The trade unions contributed 93 percent of the Labor’s Head Office’s general election income, while direct mail fund-raising produced a net profit of £252,000 (6 percent of the total raised). Although, in 1987, the Labor’s Head Office general election income (£4.2 million) was much higher than in 1983, it fell short of campaign expenditures by £159,000. Similarly, routine Head Office spending rose faster than income from trade union and constituency affiliation fees. The deficit in the general (routine) fund totaled £497,000 in 1986 and the Head Office’s overall deficit between 1984 and 1987 totaled £1.3 million.

Table 2 Labor Central Income and Expenditure 1982-1988 (£m)

Over the entire 1983-1987 parliamentary cycle, Conservative central spending (routine and campaign) was about 30 percent greater than Labor’s. The Conservative margin over Labor was only 15 percent in terms of routine spending, but Conservatives spent twice as much as Labor in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- About the Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 British Party Funding, 1983-1988

- 2 Developments in Australian Election Finance

- 3 American Presidential Elections, 1976-1992

- 4 U.S. State-Level Campaign Finance Reform

- 5 The Cost of Election Campaigns in Brazil

- 6 Regulation of Political Finance in France

- 7 Problems in Spanish Party Financing

- 8 Regulation of Party Finance in Sweden

- 9 Dutch Political Parties: Money and the Message

- 10 Political Finance in West Germany

- 11 Citizens’ Cash in Canada and the United States

- 12 The Reform Efforts in India

- 13 Financing Political Parties in South Korea: 1988-1991

- 14 Political Finance and Scandal in Japan

- Index