![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

We begin with a historical survey of the exciting early days of metallurgical research during which bainite was discovered, covering the period up to about 1960, with occasional excursions into more modern literature. The early research was usually well conceived and was carried out with enthusiasm. Many of the original concepts survive to this day and others have been confirmed using the advanced experimental techniques now available. The thirty years or so prior to the discovery of bainite were in many respects formative as far as the whole subject of metallurgy is concerned. The details of that period are documented in the several textbooks and articles covering the history of metallurgy,1 but a few facts deserve special mention, if only as an indication of the state-of-the-art for the period between 1920-1930.

The idea that martensite was an intermediate stage in the formation of pearlite was no longer accepted, although it continued to be taught until well after 1920. The β-iron controversy, in which the property changes caused by the paramagnetic to ferromagnetic transition in ferrite were attributed to the existence of another allotropic modification (β)of iron, was also in its dying days.2 The first evidence that a solid solution is an intimate mixture of solvent and solute atoms in a single phase was beginning to emerge (Bain, 1921b,a) and it soon became clear that martensite consists of carbon dispersed atomically as an interstitial solid solution in a tetragonal ferrite crystal. Austenite was established to have a face-centred cubic crystal structure, which could sometimes be retained to ambient temperature by quenching. Bain had already proposed the homogeneous deformation which could relate the face-centred cubic and body-centred cubic or body-centred tetragonal lattices during martensitic transformation. It had been established using X-ray crystallography that the tempering of martensite led to the precipitation of cementite, or to alloy carbides if the tempering temperature was high enough. Although the surface relief associated with martensitic transformation had been observed, its importance to the mechanism of transformation was not fully appreciated. Widmanstätten ferrite had been identified and was believed to precipitate on the octahedral planes of the parent austenite; some notions of the orientation relationship between the ferrite and austenite were also being discussed.

It was an era of major discoveries and great enterprise in the metallurgy of steels. The time was therefore ripe for the discovery of bainite. The term “discovery” implies something new. In fact, microstructures containing bainite must have been encountered prior to the now acknowledged discovery date, but the phase was never clearly identified because of the confused microstructures that followed from the continuous cooling heat treatment procedures common in those days. A number of coincidental circumstances inspired Bain and others to attempt isothermal transformation experiments. That austenite could be retained to ambient temperature was clear from studies of Hadfield’s steel which had been used by Bain to show that austenite has a face-centred cubic structure. It was accepted that increasing the cooling rate could lead to a greater amount of austenite being retained. Indeed, it had been demonstrated using magnetic techniques that austenite in low-alloy steels could exist at low temperatures for minutes prior to completing transformation. The concept of isothermal transformation was already exploited in industry for the manufacture of patented steel wire, and Bain was aware of this through his contacts at the American Steel and Wire Company. He began to wonder “whether exceedingly small heated specimens rendered wholly austenitic might successfully be brought unchanged to any intermediate temperature at which, then their transformation could be followed” and he “enticed” E. C. Davenport to join him in putting this idea into action.

1.1 The Discovery of Bainite

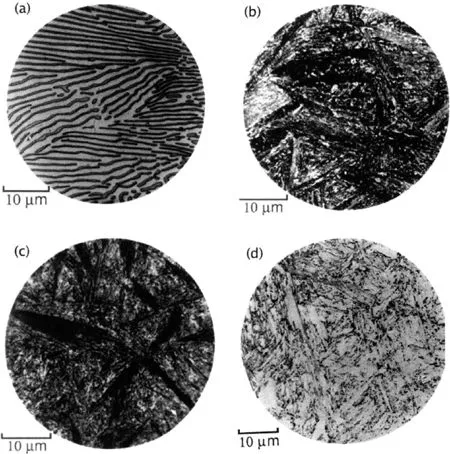

During the late 1920s, in the course of these pioneering studies on the isothermal transformation of austenite at temperatures above that at which martensite first forms, but below that at which fine pearlite is found, Davenport and Bain (1930) discovered a new microstructure consisting of an “acicular, dark etching aggregate” which was quite unlike the pearlite or martensite observed in the same steel (Fig. 1.1). They originally called this microstructure “martensite-troostite” since they believed that it “forms much in the manner of martensite but is subsequently more or less tempered and succeeds in precipitating carbon”.

The structure was found to etch more rapidly than martensite but less so than troostite (fine pearlite). The appearance of “low-range” martensite-troostite (formed at temperatures just above the martensite-start temperature MS) was found to be somewhat different from the “high-range” martensite-troostite formed at higher temperatures. The microstructure exhibited unusual and promising properties; it was found to be “tougher for the same hardness than tempered martensite” (Bain, 1939), and was the cause of much excitement at the newly established United States Steel Corporation Laboratory in New Jersey. It is relevant to note here the contributions of Lewis (1929) and Robertson (1929), who were the first to publish the results of isothermal transformation experiments on eutectoid steel wires, probably because of their relevance to patented steel. But the Davenport and Bain experiments were unique in showing the progressive nature of the isothermal transformation of austenite, using both metallography and dilatometry, and in providing a clear interpretation of the structures. Others may have published micrographs of structures that could be identified now as bainite, generated by isothermal transformation, for example Robertson, but the associated discussion is not stimulating. This conclusion remains contentious (Bhadeshia, 2013b; Hillert, 2011).3 The present author is convinced about the clarity of the Davenport and Bain experiments, which were particularly successful because they utilised very thin samples. Their method of representing the kinetic data in the form of time-temperature-transformation curves turned out to be so simple and elegant, that it would be inconceivable to find any contemporary materials scientist who has not been trained in the use or construction of “TTT” diagrams.

In 1934, the research staff of the laboratory named the microstructure “Bainite” in honour of their colleague E. C. Bain who had inspired the studies, and presented him with the first ever photomicrograph of bainite, taken at a magnification of × 1000 (Smith and Bowles, 1960; Bain, 1963).

The name “bainite” did not immediately catch on. It was used rather modestly even by Bain and his co-workers. In a paper on the nomenclature of transformation products in steels, Vilella et al. (1936) mentioned an “unnamed, dark etching, acicular aggregate somewhat similar to martensite” when referring to bainite. Hoyt, in his discussion to this paper appealed to the authors to name the structure, since it had first been produced and observed in their laboratory. Davenport (1939) ambiguously referred to the structure, sometimes calling it “a rapid etching acicular structure”, at other times calling it bainite. In 1940, Greninger and Troiano used the term “Austempering Structures” instead of bainite. The 1942 edition of the book The Structure of Steel (and its reprinted version of 1947) by Gregory and Simmons contains no mention of bainite.

The high-range and low-range variants of bainite were later called “upper bainite” and “lower bainite” respectively (Mehl, 1939) and this terminology remains useful to this day. Smith and Mehl (1942) coined the term “feathery bainite” for upper bainite which forms largely, if not exclusively, at the austenite grain boundaries in the form of bundles of plates, and only at high reaction temperatures, but this description has not found frequent use. Both upper and lower bainite were found to consist of aggregates of parallel plates, aggregates which were later designated sheaves of bainite (Aaronson and Wells, 1956).

Figure 1.1 Microstructures in a eutectoid steel, (a) Pearlite formed at 720°C; (b) bainite obtained by isothermal transformation at 290°C; (c) bainite obtained by isothermal transformation at 180°C; (d) martensite. The micrographs were taken by Vilella and were published in the book “The Alloying Elements in Steel” (Bain, 1939). Notice how the bainite etches much darker than martensite, because its microstructure contains many fine carbides.

1.2 The Early Research

Early work into the nature of bainite continued to emphasise its similarity with martensite. Bainite was believed to form with a supersaturation of carbon (Wever and Lange, 1932; Wever and Jellinghaus, 1932; Portevin and Chevenard, 1937; Portevin and Jolivet, 1938). It had been postulated that the transformation involves the abrupt formation of flat plates of supersaturated ferrite along certain crystallographic planes of the austenite grain (Vilella et al., 1936). The ferrite was then supposed to decarburise by rejecting carbon at a rate depending on temperature, leading to the formation of carbide particles which were quite unlike the lamellar cementite phase associated with pearlite. The transformation was believed to be in essence martensitic, “even though the temperature be such as to limit the actual life of the quasi-martensite to millionths of a second”. Bain (1939) reiterated this view in his book “The Alloying Elements in Steel”. Isothermal transformation studies were by then becoming very popular and led to a steady accumulation of data on the bainite reaction, still variously referred to as the “intermediate transformation”, “dark etching acicular constituent”, “acicular ferrite”, etc.

In many respects, isothermal transformation experiments led to the clarification of microstructures, since individual phases could be studied in isolation. There was, however, room for difficulties even after the technique became well established. For alloys of appropriate composition, the upper ranges of bainite formation were found to overlap with those of pearlite, preceded in some cases by the growth of proeutectoid ferrite. The nomenclature thus became confused since the ferrite which formed first was variously described as massive ferrite, grain boundary ferrite, acicular ferrite, Widmanstätten ferrite, etc. On a later view, some of these microconstituents are formed by a “displacive” or “military” transfer of the iron and substitutional solute atoms from austenite to ferrite, and are thus similar to carbon-free bainitic ferrite, whereas others form by a “reconstructive” or “civilian” transformation which is a quite different kinetic process (Buerger, 1951; Christian, 1965a).

1.2.1 Crystallography

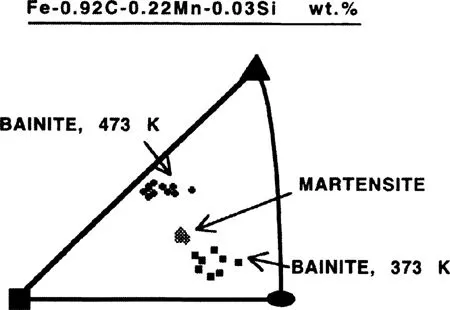

By measuring the crystallographic orientation of austenite using twin vestiges and light microscopy, Greninger and Troiano (1940) were able to show that the habit plane of martensite in steels is irrational. These results were consistent with earlier work on non-ferrous martensites and put paid to the contemporary view that martensite in steels forms on the octahedral planes of austenite. They also found that with one exception, the habit plane of bainite is irrational, and different from that of martensite in the same steel (Fig. 1.2). The habit plane indices varied with the transformation temperature and the average carbon concentration of the steel. The results implied a fundamental difference between bainite and martensite. Because the habit plane of bainite approached that of Widmanstätten ferrite at high temperatures, but the proeutectoid cementite habit at low temperatures, and because it always differed from that of martensite, Greninger and Troiano proposed that bainite from the very beginning grows as an aggregate of ferrite and cementite. A competition between the ferrite and cementite was supposed to cause the changes in the bainite habit, the ferrite controlling at high temperatures and the cementite at low temperatures. The competition between the ferrite and cementite was thus proposed to explain the observed variation of bainite habit plane. The crystallographic results were later confirmed using an indirect and less accurate method (Smith and Mehl, 1942). These authors also showed that the orientation relationship between bainitic ferrite and austenite does not change very rapidly with transformation temperature and carbon content and is within a few degrees of the orientations found for martensite and Widmanstätten ferrite, but differs considerably from that of pearlitic ferrite/austenite. Since the orientation relationship of bainite with austenite was not found to change, Smith and Mehl considered Greninger and Troianos’ explanation for habit plane variation to be inadequate, implying that the habit plane cannot vary independently of the orientation relationship. The fact that the habit plane, orientation relationship and shape deformation cannot be varied independently was proven later with the crystallographic theory of martensite (Bowles and Mackenzie, 1954; Wechsler et al., 1953).

1.2.2 The Incomplete Reaction Phenomenon

It was known as long ago as 1939 that in certain alloy steels “in which the pearlite change is very slow”, the extent of transformation to bainite decreases, ultimately to zero, as the transformation temperature is increased (Allen et al., 1939). For example, the bainite transformation in a Fe-2.98Cr-0.2Mn-0.38C wt% alloy was found to begin rapidly but cease shortly afterwards, with the maximum volume fraction of bainite obtained increasing with decreasing transformation temperature (Klier and Lyman, 1944). At no temperature investigated did the complete transformation of austenite occur solely by decomposition to bainite. The residual austenite remaining untransformed after the cessation of the bainite reaction, reacted by another mechanism (pearlite) only after a further long delay. Cottrell (1945), in his experiments on a low-alloy steel, found that the amount of bainite that formed at 525°C (≪C Ae3) was negligible, and although the degree of transformation increased as the isothermal reaction temperature was decreased, the formation of bainite appeared to stop before reaching completion. Other experiments on chromium-containing steels revealed that the dilatometric expansion due to bainite became larger as the transformation temperature was reduced, Fig. 1.3 (Lyman and Troiano, 1946). Oddly enough, the bainite transformation did not seem to reach completion on isothermal heat treatment, even though all of the austenite could readily transform to pearlite at a higher transformation temperature (Klier and Lyman, 1944). Often, the transformation of austenite at lower temperatures occurred in two stages, beginning with the bainite reaction which stopped prematurely, to be followed by the formation of pearlite at a slower rate. It is significant that the two reactions may only be separated by a long delay in well-alloyed steels; in plain carbon steels “the second reaction sets in within a few seconds after the beginning of the bainite reaction” (Klier and Lyman, 1944).

Figure 1.2 An example of the results obtained by Greninger and Troiano (1940), showing the i...