- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Basic Benefits and Clinical Guidelines

About this book

This book explains how clinical guidelines might be used to define health care needs and basic benefits. It discusses certain technical issues of the model proposal, including the importance of considering both health outcome evidence and patient and public preferences.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

The Model Proposal: Designing Basic Benefit Plans Using Clinical Guidelines

1

Defining Our Terms

David C. Hadorn and Robert H. Brook

This book presents an attempt to advance the debate concerning the problems of how to distribute health care resources in a fair and efficient manner. The scope and significance of this debate has increased substantially of late because of ever-rising health care costs, increasing concerns about inequitable access to care, and mounting evidence that inappropriate and unnecessary care continues to be delivered to patients in significant quantities.

A solution to these problems would likely be facilitated if those engaged in the health care resource allocation debate were to adopt clear and consistent definitions for certain critical terms - particularly rationing, "health care needs," and "basic benefit plans." In this chapter we propose definitions for these key terms and explain how each concept relates to the idea of defining basic benefits using necessary-care guidelines.

Let's begin with the word "rationing."

“Rationing”

According to the dictionary, "ration[ing] refers to equitable division of scarce items, often necessities, by a system that limits individual portions" (American Heritage Dictionary 1987). During World War II, for example, coupons good for a fixed amount (i.e., a ration) of meat and butter were distributed among citizens according to rules established by social planners.

Only two types of medical and surgical services are currently scarce relative to demand: organs for transplantation (Rapaport 1987, McDonald 1988) and, sometimes, beds in intensive care units (ICUs). Patients in need of organ transplants must (at least in theory) "wait in line," regardless of their wealth or insurance status, to receive their ration of (usually) one organ. Thus, an equitable plan exists to distribute a physically scarce resource among individuals identified to be in need. This is rationing in the traditional, or classical, sense. In the case of ICU beds, physicians often ration care informally by modifying criteria for admission and discharge based on the number of available beds (Singer et al. 1983, Selker et al. 1987).

Use of the word "rationing" in the contemporary policy debate has clearly transcended this original meaning. Far from carrying connotations of fairness, for example, the "R-word" has now come to represent discrimination on the basis of socioeconomic status. Concerned about this transformation in usage, Michael Reagan (1988) has urged that

we agree to use "price allocation" to describe the workings of the market system and reserve "rationing" for situations of deliberate sharing of a scarce commodity. . . . [T]o call what we are now doing rationing is to dignify what is really discrimination in access to health care services on the basis of income, and thereby to defuse criticism of this highly questionable practice.

Retaining the connotations of physical scarcity and fairness within the word "rationing" will be difficult, however, in view of the broader meanings now almost universally imputed to the word (Callahan 1988, Blank 1988). This broader usage generally follows Henry Aaron and William Schwartz' widely quoted definition (1984) to the effect that rationing occurs when "not all care expected to be beneficial is provided to all patients." For example, Arnold Relman (1990a) recently called rationing "the deliberate and systematic denial of certain types of services, even when they are known to be beneficial, because they are deemed to be too expensive" (emphasis supplied).

Other recent definitions of "rationing" move even farther from the word's original roots in scarcity and fairness. In an article entitled "Health care rationing through inconvenience," Gerald Grumet (1989) in effect equated "rationing" with "cost-containment"; indeed, the word "rationing" did not appear anywhere in the article except in the title. Daniel Callahan (1990a) has advocated the "rationing of medical progress," meaning the deliberate curtailment of certain forms of applied medical research (e.g., artificial hearts). Aaron and Schwartz (1990) have recently re-described rationing as "the denial of commodities to those who have the money to buy them." John Kitzhaber, architect of the Oregon Medicaid priority-setting project, often argues that Medicaid programs "ration people" by changing eligibility standards so as to disenroll some beneficiaries. Even more far afield, a correspondent to the American Medical News advocated that we "ration back prosperity to the people of this country. . . ." (Brindle 1989)

How should the word "rationing" be used? The answer, we believe, lies in considering how the word might be made most useful to the resource allocation debate. On the one hand, if we abandon the original connotations of scarcity and fairness, what shall we call situations (e.g., organ transplants) where genuine scarcity in fact exists -- along with an equitable plan for dealing with that scarcity? On the other hand, the notion that rationing is potentially unfair and discriminatory, or at the very least something to be avoided if possible, seems indelibly ingrained in the collective consciousness of American society.

We believe that the best solution is to restrict the use of "rationing" to something close to Relman's definition: the withholding of services acknowledged to be beneficial, based on ability to pay. Such withholding is potentially far more common and problematic than are the isolated areas of medicine (e.g., organ transplants) to which the traditional meaning of "rationing" can be legitimately applied.

We do not, however, believe that the withholding of care must be "deliberate and systematic," as Relman would have it. Simple toleration by society of inequitable barriers to effective care should also qualify as rationing; otherwise it would be too easy for society to say that it simply "cannot" produce an equitable situation, and that the situation is, therefore, not deliberately brought about. ("Inequitable barriers" here refers primarily to restrictions on access due to wealth or insurance status, but could be extended to race and other socio-demographic factors. Geographic distance ordinarily would not count as an inequitable barrier, any more than the reduced availability of police and fire protection in rural areas is today considered unfair to the people who choose to live in the country.)

Another important consideration with respect to defining "rationing" is that withholding care acknowledged to be beneficial is potentially avoidable through the identification and elimination of useless or "marginal" care. Robert Brook and Kathleen Lohr (1986) have estimated that 30% or more of the health care services currently rendered in this country might safely be forgone, and that elimination of this subset of care could permit society to save enough money to avoid the need to ration effective health care. Subsequent studies (Chassin et al. 1987, Winslow et al. 1988, Brook et al. 1990a, Chassin et al. 1989) and a recent review of available literature (Brook et al. 1990b) tend to confirm Brook and Lohr's view in this area. Nevertheless, whether or not the elimination of unnecessary services would save enough money to provide all necessary services must be considered unresolved at this time. Answers to this important empirical question may begin to emerge when the results of current and future outcome studies appear. Much will depend, of course, on how stringently services are judged with respect to the degree to which they provide demonstrated, significant net health benefit. Do a few days of extra life constitute a significant net benefit?

If, in fact, sufficient savings can be realized from the curtailment of payment for unnecessary care, American society might avoid rationing (in Relman's sense of the word) by identifying sufficiently beneficial or effective services and providing coverage for these services under all basic-level plans. Thus, a further advantage to the recommended, restricted use of the word "rationing" is that society remains able to distinguish between the withholding of truly effective care (rationing) from the curtailment of services of dubious or unproven benefit (not rationing). The distinction is vital and should be clearly maintained both conceptually and in our language.

One final point before moving on. Aaron and Schwartz (1990) have observed that the elimination of marginal or useless care would result in only one-time savings, because new essential services are created continuously through research. This is the primary reason that Callahan has suggested (1990a) that certain types of medical progress be "rationed," as noted above. While limits on (tax-supported) medical innovation may be necessary some day, we believe that by subjecting new technology to strict evaluations of expected benefit before extending coverage under insurance plans, the so-far unbridled tide of "progress" can be reined in to a significant extent. Moreover, it should be noted that even a one-time savings of (anything like) 30% of our current $750 billion annual health care budget is a worthwhile goal in itself.

Health Care Needs

So far, we have defined "rationing" as the toleration of inequitable access to beneficial services. An important modification is required in this definition before we are finished.

A clear and important connotation found in the original scarcity/fairness usage of "rationing" (and in the dictionary definition cited earlier) is that rationed goods and services are necessary or bask to a continued decent existence. Food and water -- two basic necessities are rationed around the world today, but automobiles and television sets are not rationed anywhere, because these latter commodities are not considered necessary to a minimally decent life. Judgment may sometimes be required, of course, to distinguish truly necessary commodities (e.g., heating oil) from unnecessary ones (e.g., gasoline for an automobile when adequate public transportation is available).

The notion of necessity as it pertains to health care rationing is not completely captured by commonly used words like "beneficial," "effective," or "appropriate." Indeed, it is clearly possible for a medical service to be beneficial or appropriate without being truly necessary. This distinction is evident in the definition of "appropriate care" developed by RAND investigators (Park et al. 1986): a service is considered appropriate to the extent it is, all things considered, "worth doing." But is appropriate care (viz., care worth doing) the same thing as necessary care? How appropriate (e.g., on RAND's 1-9 scale) must a service be before it is considered necessary, and with what level of physician agreement? Work is underway at RAND to address these issues. In the meantime, we conclude that the definition of rationing should be modified to mean the withholding of care duly deemed necessary ~ as opposed to effective, appropriate, or beneficial.

In the same editorial cited above, Relman (1990a) connected rationing with needs in a manner similar to that just described. Arguing against rationing, Relman noted that "in a country that spends as much as we do on health care, there should be no need to deny medically necessary services (including the best of modern technology) to anyone" [emphasis supplied]. More recently, Relman (1990b) further decried rationing, stating that ". . . we should be able to afford all the services we really need, provided we use our resources wisely" [emphasis supplied].

The connection between medical needs and rationing is fundamental to a clear understanding of the current policy debate. If we can identify "really necessary" health care interventions, and ensure that all patients have equitable access to these interventions, rationing can be avoided.

The main difficulty with this plan, of course, lies in the ambiguity inherent in the concept of health care needs. The notion of needs, as Callahan (1987) has observed, when set "in the context of constant technological innovation, is inherently elastic and open-ended." Similarly, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine (1983) avoided the concept of health care needs, observing that "medical need is often not narrowly defined but refers to any condition for which medical treatment might be effective."

We believe it is possible to "arrowly define" need so as to permit the salutary application of this critical concept to the health care resource allocation debate. To do so, it will be necessary to develop objective criteria by means of which health care needs can be distinguished from "mere desires." Some form of objective criteria is always required to evaluate claims of need against others or against society (Scanlon 1975).

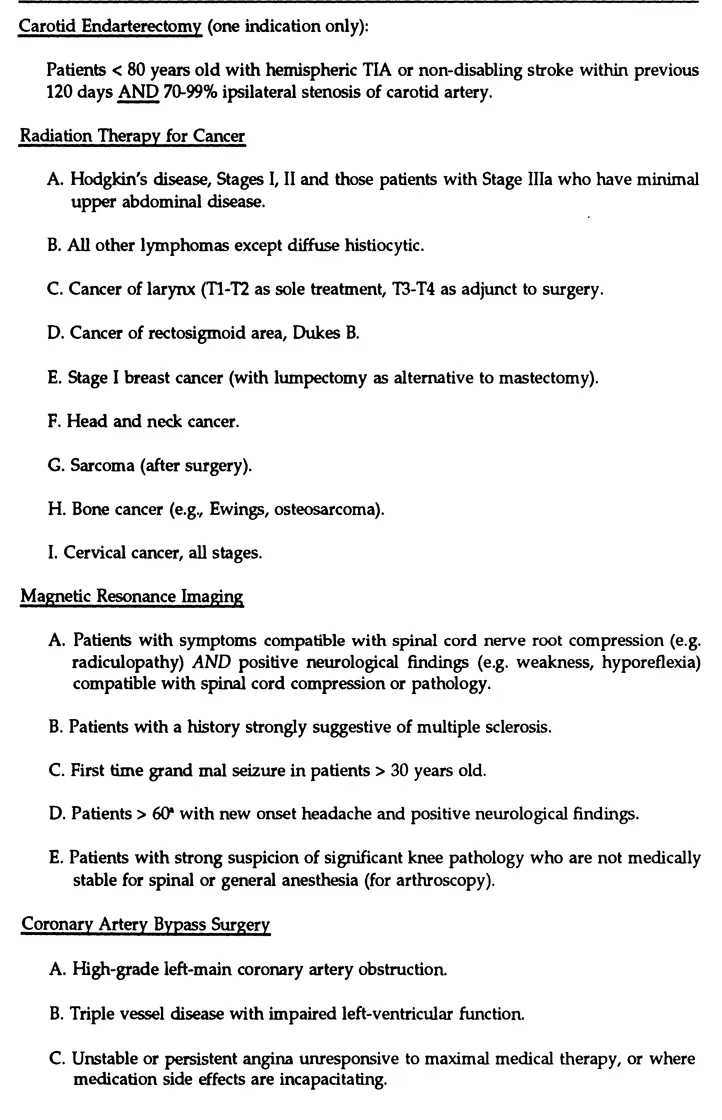

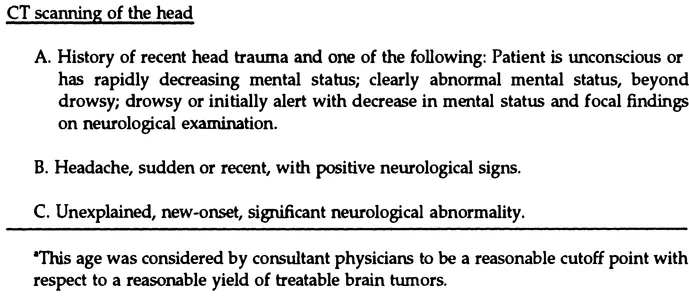

In the case of health care, suitable objective criteria might coherently take the form of a special type of clinical guideline -- necessary-care guidelines -- that would depict the indications (or "types of patients") for which specified services are considered necessary. These guidelines would be developed by duly constituted bodies or panels, based on available outcome data, public testimony, and expert consensus. Necessary-care guidelines would specify the clinical indications for which various interventions (Figure 1.1) have been "clearly demonstrated ('Cor reasonably well demonstrated') to provide significant net health benefit over no or alternative treatment." "Net benefit" would be defined in terms of longevity plus quality of life. Services judged to provide only insignificant net health benefits (or whose benefits are deemed to have been inadequately demonstrated) would be considered unnecessary, and desires for such services would not be acknowledged as needs. Guidelines would be updated regularly and appeals mechanisms would be available to accommodate atypical patient cases. (Chapter 2 provides a more detailed discussion of the necessary-care guideline concept).

Defining health care needs using clinical guidelines would allow us to determine -- in a way we are unable to do today -- whether, in fact, care is being rationing (i.e., necessary care is being withheld), and if so to what extent. Without such an objective depiction of needs it is difficult to see how claims of rationing can be validated, or how potential solutions to the access problem might be evaluated. Thus, by speaking a common language we can hope both to identify legitimate health care needs and to monitor whether and to what extent rationing is occurring. The benefit of clear language and definitions is again apparent.

The proposed development and use of necessary-care guidelines attempts to breathe new life into the concept of health care needs, which, because of problems of definition, has been all but abandoned as a possible foundation for reforming the health care system. Yet an appeal to health care needs remains the most inherently sensible and potentially potent answer to the nagging, fundamental question: "When should society (particularly taxpayers) pay for medical tests and treatments when patients can't afford them?" The simple answer: "Only when they really need them." Poll after poll has demonstrated the egalitarian spirit of the American public. Although a simultaneous reluctance to pay more for health care often tempers this spirit, the fact remains: we really do want to ensure that people obtain the things they really need.

FIGURE 1.1 Draft Necessary-Care Guidelines

Source: These draft guidelines represent our interpretation of informal conversations with physician colleagues, each of whom was asked to specify the indications for which the respective procedure has been "reasonably well demonstrated to provide significant net health benefit vs. non-treatment." "Benefit" was restricted to final outcomes (viz., longevity plus quality of life), rather than considering only intermediate outcomes (e.g., tumor shrinkage). In some cases quality-of-life penalties (i.e., side effects) of treatment may "cancel out" possible longevity benefits. Although reasonable care was taken in developing these draft guidelines, no representation is made that they are accurate or inclusive, nor that they resemble the "necess...

Source: These draft guidelines represent our interpretation of informal conversations with physician colleagues, each of whom was asked to specify the indications for which the respective procedure has been "reasonably well demonstrated to provide significant net health benefit vs. non-treatment." "Benefit" was restricted to final outcomes (viz., longevity plus quality of life), rather than considering only intermediate outcomes (e.g., tumor shrinkage). In some cases quality-of-life penalties (i.e., side effects) of treatment may "cancel out" possible longevity benefits. Although reasonable care was taken in developing these draft guidelines, no representation is made that they are accurate or inclusive, nor that they resemble the "necess...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- PART ONE The Model Proposal: Designing Basic Benefit Plans Using Clinical Guidelines

- PART TWO Analysis of the Model Proposal

- PART THREE Counterpoint: The Oregon Medicaid Experiment

- Epilog

- References

- About the Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Basic Benefits and Clinical Guidelines by David C. Hadorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Insurance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.