![]()

Biology and Ecology

![]()

7

The Ecological Nature of the Fire Ant: Some Aspects of Colony Function and Some Unanswered Questions

W. R. Tschinkel

Presented here is a conceptual interpretation of the available facts about fire ants that will be used to paint a general picture of their biological nature and function. Considering the gaps in our knowledge, the future may very well see changes of interpretation. The facts upon which I base my review are the results of the work of many people over more than three decades. Information on history and spread of Solenopsis invicta is discussed by Lofgren in Chapter 4.

Ecological Nature of S. Invicta

Ecologically, S. invicta is a weed species and, as such, shows many of the biological properties of weeds. Weeds are animal or plant species that are adapted for the opportunistic exploitation of ecologically disturbed habitats. Naturally, these are created by flood, fire, and storm and consist of new sandbanks, slumps, and landslides, burns, and windfalls. Man, however, creates vast areas of disturbed habitat by clearing forest for agricultural, domestic, and other uses. The plant and animal communities that occupy such disturbed habitats are called early secondary or early succession communities because, if left alone, they will gradually revert to dominant climax communities. In the southeast, this is mostly deciduous forests. Because such early succession communities are ephemeral and underexploited, the weed species utilizing these habitats are adapted for very rapid, scramble-type exploitation with an emphasis on high reproductive rates and efficient dispersal rather than competition with other members of the community (Ito 1980).

The weed-like properties of the fire ant are as follows: First, the fire ant is clearly and dramatically associated with ecologically disturbed habitats created mostly by man both in the United States and South America (Banks et al. 1985). Thus, S. invicta is abundant in old fields, pastures, lawns, roadsides, and any other open, sunny habitats. It shares these habitats with many other weedy plant and animal species, from man's crops to lawn and pasture grasses, goldenrods, and dog-fennel. Man is the fire ant's greatest friend, even though the sentiment may not be returned.

On the other hand, the fire ant is absent or rare in late succession or climax communities such as mature deciduous or pine forest (personal observation). When it is found in these communities, it is usually associated with local disturbances such as seasonal flooding and roads. In North Florida, on transects through longleaf pine-wiregrass-turkey oak forest, I found S. invicta strictly associated with temporary ponds or pond margins, graded dirt roads, and the margins of paved roads. All other areas were occupied by S. geminata, if any fire ants were present at all. This was true even in recently clearcut and replanted areas. Increased insolation associated with disturbance is thus not sufficient explanation for S. invicta's distribution. Unfortunately, there are almost no data on the biotic and abiotic causes of its distribution. Nevertheless, it is clear that S. invicta, like other weeds, is associated with open, disturbed habitats. This also appears to be true in its native homeland in Southern Brazil (Buren, personal communication; Banks et al. 1985).

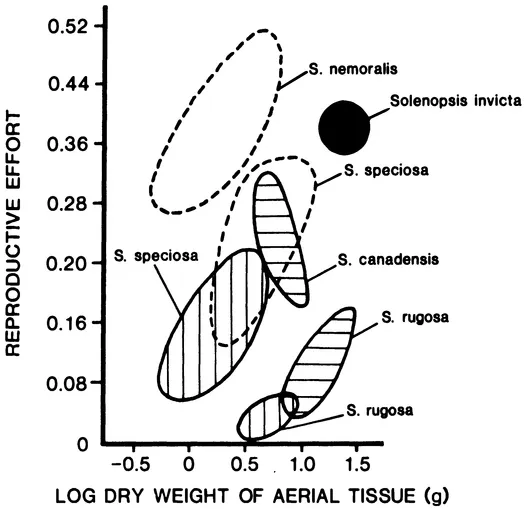

A high reproductive rate is a second weedy property that is associated with the sporadic, unpredictable and ephemeral availability of suitable habitat (in the absence of man-made disturbance). Success in such a situation goes to the animals and plants that "gits thar the fustest with the mostest" (attributed to Civil War General Lee DeForrest in response to being asked how to win a battle) with little attention paid to competition within the community. Fire ants, like other weeds, achieve a high reproductive rate in part by very high investment of resources in reproductives. From the meager data available (Markin et al. 1973; Morrill 1974), I estimate that S. invicta allocates 30 to 40% of its annual biomass production to sexuals. This is similar to the energy allocation to seeds found in weedy species of goldenrod and much higher than non-weedy goldenrods adapted to competition in late-succession communities (Ito 1980) (Fig. 1). Thus, the average fire ant colony in North Florida produces about 4500 sexuals per year (Morrill 1974). Although very little information is available for comparison, this seems high for ants in general and is almost certainly an adaptation to its weedy habits.

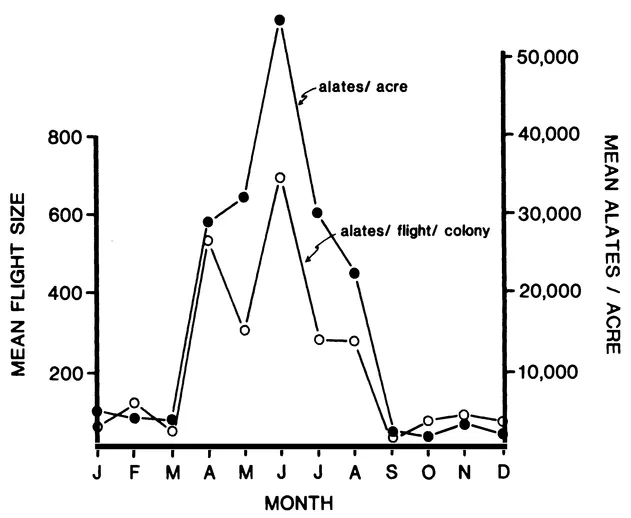

A third weedy property is effectiveness of dispersal and colonization. In the absence of man-made disturbance, secondary habitat is scattered and unpredictable. Its exploitation depends upon the ability to scatter propagules (sexuals or seeds) over wide areas on the chance that a few will find their way to an appropriate site and colonize it. The fire ant achieves this by producing a large number of sexuals who take part in high-altitude, dispersive mating flights throughout a large portion of the year (Fig. 2). The queens often fly or are wind-carried one-fourth to one-half mile or more before settling to the ground although most settle at shorter distances (Markin et al. 1971).

FIGURE 1. Reproductive effort (proportion of production invested in seeds or sexuals) in relation to size of organism or colony for goldenrods (Solidago spp.) and fire ants (black circle). Each enclosed area is represented by the individuals of a single population on a dry site (enclosed in dotted curve), a wet site (with horizontal shading), or a hardwood site (vertical shading) (modified from Ito 1980).

Fire ant queens do not have to depend on general habitat disturbances to enhance their ability to establish a colony; even a specific disturbance to the ant community can provide the necessary conditions for success. This phenomenon was first observed by Summerlin et al. (1977) in mirex-treated plots in which S. invicta was a minor component of the ant community. The mirex killed almost all of the ground-nesting ants; but after recolonization, S. invicta and another weedy species, Conomyrma insana, had greatly increased their dominance over all other species (Fig. 3). Many of the native species did not reappear in the course of this two-year study.

FIGURE 2. Occurrence and size of mating flights throughout the year in North Florida (from Morrill 1974).

The implication of these studies is clear: Large-scale, unspecific control programs utilizing chemical baits in areas of low fire ant populations may aid rather than hinder the estab...