- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Choices and Chances is an ideal supplement to introductory textbooks. By showing how theories can apply to everyday life, it demonstrates the ways sociology—a living, growing discipline—can shed light on issues of immense personal and social importance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Choices And Chances by Lorne Tepperman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Patterns of Desire

Why You Want What You Want

Introduction

Life in a modern society is full of choices. People seem to like having choices, but choosing well is difficult. The consequences of a wrong choice can be costly and painful. Taking responsibility for our choices is often unpleasant. We can close our eyes and try to pretend that there is only one way to live, but few of us these days can believe that for very long. Evidence of different kinds of lives surrounds us. The more we learn about the world, the more variety we can see, and the more things we learn to want. We find that we can choose for or against things in a great many situations.

Looked at in a different way, however, none of our choices is free. Every choice has a cost, if only the cost of giving up another choice we might have made. Moreover, every choice is limited by what we know, who we are, and what we have to trade for the thing we want. In those respects some people have more choice than others, a better choice of possible lives. But no one has unlimited choice, and no choice is cost-free. That is a condition of living.

Many major experiences in life are not chosen at all. These may include unwanted pregnancies, marriage breakdowns, forced unemployment, disabling accidents, abusive parents, betrayal by friends, the outbreak of war, and economic depression. They may also include passionate love, lucky winnings, devoted friends, inborn skills and aptitudes, peace, and prosperity. You are not to blame for the first category of experiences or to be praised for the second. These are simply the contexts within which you live your life.

Within this human condition, we all work out our life's desires. This fact never changes; only situations and desires change. Thus, anyone writing a book about life choices must look at the world as it exists today and ask, What do people want out of life? What satisfies them? What are people's main concerns? What kinds of people are most satisfied with their lives, and how do they get to be that way?

These are the kinds of questions we hope to answer in this book. Philosophers have been discussing these questions for thousands of years: The answers are important and hard to discover. We hope to answer these questions not as philosophers but as sociologists, using evidence collected from the people around us.

Answering these questions will take the whole book. This chapter introduces the questions in their most general form, in relation to life satisfaction. It opens with a discussion of the kinds of people who are most satisfied with life and concludes by examining two theories that try to explain why people want what they want and why they are satisfied with what they get.

People are complicated. Their mix of motives defies easy generalization. Moreover, people provide exceptions to every rule that social science can devise. It is this complexity of people—indeed, of everyday life—that makes social science challenging. Like natural scientists, historians, and novelists, sociologists seek the underlying order in apparent chaos: the laws that govern and predict tomorrow's universe. Let us begin by showing that this goal is at least approachable.

What You Want

Most of us are rather self-centered. In other words, we are wrapped up in our own ideas, plans, and values. We rarely take the time to think about other people's point of view. Thus, we imagine that our own thoughts are unique. We believe that the things we want to get and do, the choices we plan to make in life, and even the ways we spend our time and money are uniquely our own. We may even believe that we have every opportunity to get what we want, and that with enough luck and planning, we will get it.

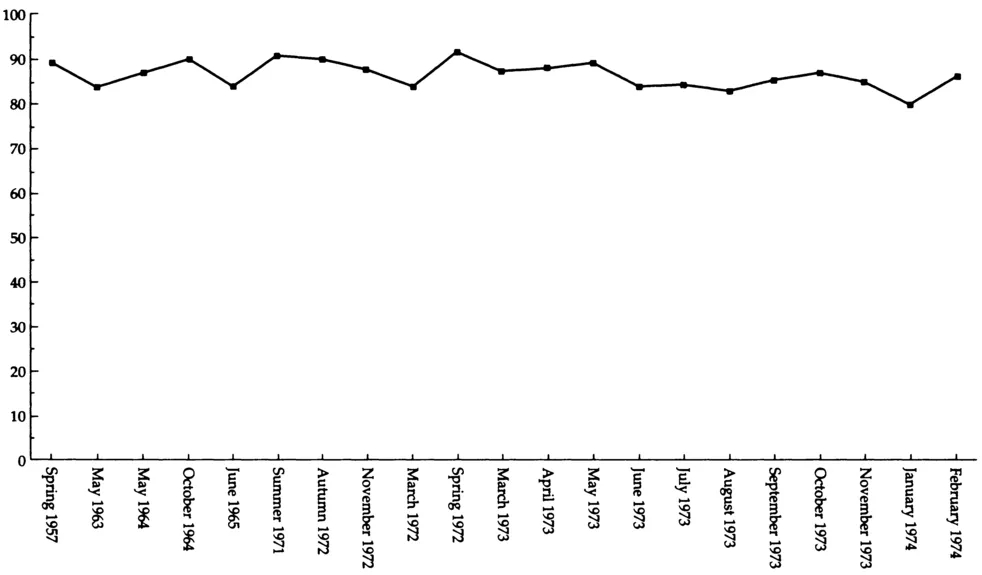

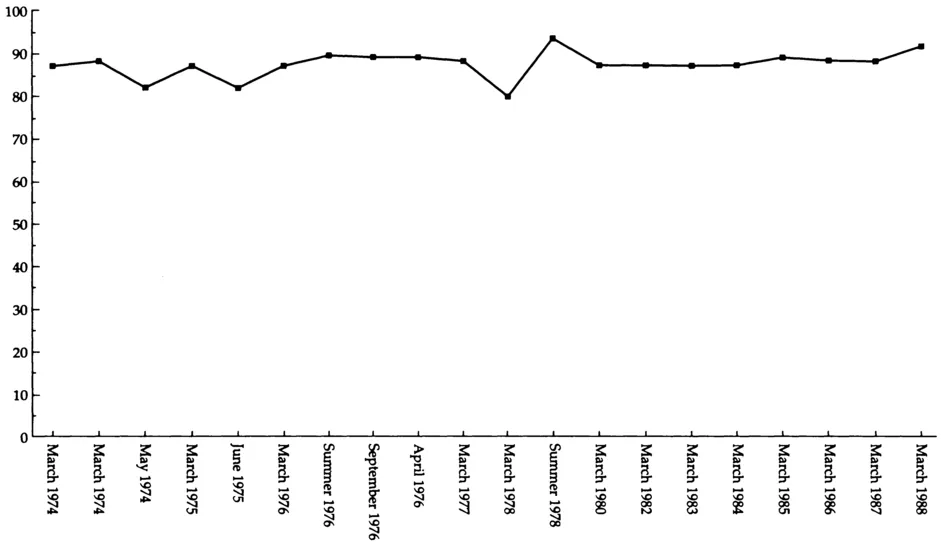

Interestingly, when asked about happiness or life satisfaction, most Americans seem quite content. Survey results covering the period from 1957 to 1988 show little change in the proportion of Americans who say they are very happy (see Exhibit 1.1). Despite political crises and economic changes, approximately one-third of Americans were very happy and only about 10 percent were not too happy throughout this period (Niemi, Mueller, and Smith, 1989, p. 290).

Maybe Roos (1988) was right in claiming that happiness is ruled by social norms: People are expected to be happy and they want to be happy.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Percentage of Americans Who Are "Very Happy" or "Pretty Happy" with the Way Things Are

SOURCE: Adapted from Niemi, R., Mueller, J., and Smith, T. (1989). Trends in Public Opinion: A Compendium of Data. (New York: Greenwood Press), p. 290.

SOURCE: Adapted from Niemi, R., Mueller, J., and Smith, T. (1989). Trends in Public Opinion: A Compendium of Data. (New York: Greenwood Press), p. 290.

So they devise strategies for being happy or at least for appearing happy. After all, unhappy people are losers, and no one wants to be a loser.

Does that make us all "contented cows," as some people fear? Not if happiness is really as useful and beneficial as research shows it is. For example, Veenhoven (1988) noted that data from around the world show that an enjoyment of life "broadens perception, encourages active involvement, and fosters political participation. It facilitates social contacts, in particular contacts with spouse and children, and buffers stress, thereby preserving health and lengthening life somewhat." He concluded that "society as a whole is more likely to flourish with happy citizens than with unhappy ones."

So Americans are generally quite upbeat; they want and expect to be happy. They are far more likely to find life exciting than dull (Niemi, Mueller, and Smith, 1989, p. 293). Less than 7 percent of Americans (in the period 1973-1989) found life very dull compared with 45-48 percent who found life exciting. Men were somewhat more likely than women to find life exciting, and whites were considerably more likely than blacks to feel life is exciting. As we might expect, feelings of excitement decline with age (Wood, 1990, p. 227).

Although Americans are ambivalent about change, they expect change to be positive in the long run (Waldrop, 1994). Young Americans are more optimistic than older Americans, although age does not necessarily bring pessimism. Sixty-eight percent of American adults under age thirty expect things to work out for the best compared with 54 percent of those aged sixty and older. Eighty-four percent feel that you can change an unhappy life if you try.

Gallup polls conducted in thirty countries during the 1980s (Michalos, 1988) asked people, "So far as you are concerned, do you think that [next year] will be better or worse than [the year just ending]?" Generally, about one-third of the people in the countries sampled were optimistic about the coming year. By this measure, the world's greatest optimists turned out to live in Argentina, Greece, Korea, and the United States, where more than half the respondents expected the next year to be better than the current one. The least optimistic countries, where less than 20 percent of respondents were optimistic about the future, were Germany, Austria, and Belgium. What do these countries have in common that might account for the great differences in optimism? Why are some people less optimistic or more satisfied with life than others? What makes people vary in this way?

We are tempted to respond, "Who knows why? People are just funny that way!" or, "Everybody's different." But we have already noted that people tend to judge their lives in similar ways. This uniformity suggests that social science may be able to explain optimism and satisfaction. When people's desires and concerns differ, they do so in patterned, predictable ways. All social science—sociology, psychology, anthropology, and other related disciplines—rests on this fact of patterned variation.

Because the issue is so basic, this chapter will concentrate on showing that people's views about life vary in patterned, predictable ways. Later chapters follow the same theme through particular domains of life: education, career, marriage, child rearing, and so on. By the end of this book, we will have found that we really can understand people's lives better with the help of social science concepts and measurements.

Just as life satisfactions are patterned, so are life goals: the things that people hope to get out of life. What are the most important life goals for Americans? What are they hoping to get out of life? American sociologist S. M. Lipset studied changing North American values and pointed out (1990, p. 2) that any effort to analyze national values must confront the fact that statements about values are necessarily comparative. So to describe Americans as individualistic begs the question, In comparison to what other countries? Canada, a country with which the United States shares much, provides an interesting point of comparison. As Lipset and others have noted, despite some interesting similarities, the differing U.S. and Canadian histories have resulted in significant differences in cultural values.

Individualism and achievement were guiding principles in the American Revolution and were later entrenched in the Declaration of Independence. American liberalism was influenced by this revolutionary tradition (Lipset, 1990, p. 3). American heroes are rebels or revolutionaries. The emphasis on individualism predicts a high commitment to personal rights, as compared with a greater emphasis in Canada on maintaining law and order. The United States has far higher rates of violent crime than Canada has, yet Americans strongly resist gun-control initiatives. Americans are risk takers; Canadians are more apt to be savers and less likely to use credit. Success is highly valued in the United States, even when achieved by somewhat questionable means (Lipset, 1990, p. 14).

Universalism—"the desire to incorporate diverse groups into a culturally unified whole" (Lipset, 1990, p. 27)—is another strong American value, one reflected in the American ideology of the melting pot. As we will see in Chapter 2, the values of universalism and individualism are sometimes difficult to rationalize. When universalism is assumed, and individuals are responsible for their own success or failure, it is easy to overlook the structural barriers of systemic discrimination that account for gender, racial, and ethnic inequalities.

In keeping with the value attached to individualism, American society emphasizes the separation of church and state. Religious expression tends to be fundamentalist. Sixty-six percent of Americans say they believe in the devil; 67 percent believe in hell; and 84 percent believe in heaven (Lipset, 1990, p. 12). Do Americans attach great importance to spirituality? There has been a great shift in religious expression over the years, a trend Glenn (1987) attributed to an increase in individualism and the emphasis on autonomy and individual freedom. This shift is reflected in declining interest in traditional forms of religious practices. From 1973 to 1983, conservative Protestant churches increased in membership while mainstream Protestant churches lost numbers (Glenn, 1987). Furthermore, the percentage of American adults who said that religion was very important in their lives declined substantially from the 1950s to the 1980s.

A Minor Digression

Now that you have some idea where this book is going, we want to stop the flow for a moment. Books by professors are famous for their digressions and attempts to limit the generality of their conclusions. There is no way to write a book like this without making some assumptions, since they simplify the argument presented. Otherwise, this book would be about 1,000 pages long. Thus, we have necessarily made some assumptions about what motivates people.

First, we are assuming that you and all other individuals want to achieve maximum satisfaction from life, Satisfaction is related to but different from happiness—at least in the eyes of people who study this problem seriously. Satisfaction is a cognitive thing; Your mind tells you if you are satisfied or not. Happiness is a visceral thing: Your guts tell you if you are happy. (For discussions of the measurement of happiness and satisfaction, see Grichting, 1983; Kammann, Farry, and Herbison, 1984; and Stones and Kozma, 1985.)

You know whether you are happy or riot, without a lot of deep soul-searching. When you're happy you feel like smiling. Your heart races and you want to jump up and down or shake hands with the person next to you. You feel great!

Happiness is a useful as well as pleasant state of being. According to a recent report (Glatzer and Bos, 1992), happiness increases a person's life expectancy, improves the quality of a marriage, increases the likelihood of finding and keeping a job, and raises a person's self-esteem and satisfaction with personal achievements.

Satisfaction is a good thing, too, but knowing whether you are satisfied is not quite as easy as knowing whether you are happy. Often you have to think for a while. In part, that's because there is a complicated relationship between how satisfied we feel with life as a whole and with particular parts (or domains) of our lives.

Sometimes we are satisfied with life as a whole and with particular domains of life (for example, with our social activities). At other times, when we feel dissatisfied with a particular domain of life (for example, with marriage), we come to feel dissatisfied with life as a whole. That is, our feelings about one domain "spill over" into our views of life as a whole. We may even come to feel that everything is falling apart. (This spillover effect is discussed in Chapter 4.)

Most of the time, the relationship between overall life satisfaction and satisfaction with particular domains is reciprocal—it runs both ways. An example is the relationship between life satisfaction and job satisfaction. Thus, when someone asks us how satisfied we are with life, we are forced to make a complex (if unconscious) assessment of a great many things all at once (Lance et al., 1989).

As well, studies have found varying degrees of correlation between happiness and satisfaction. Often, people who are happy with life are also satisfied, and vice versa. But this is not always the case. You can be satisfied without being happy and happy without being satisfied. This book focuses chiefly on satisfaction, not happiness. It assumes that people are trying to increase their satisfaction with life—not their happiness. And we believe it is easier to increase your satisfaction than your happiness.

But bear in mind that this is an assumption, and we may be wrong. In any event, the book would be different if we assumed that people were attempting to increase their happiness. You may want to spend a few moments thinking about whether it is happiness or satisfaction that you are trying to increase. (After all, you may not want to read the book if you don't care about satisfaction.)

Our second warning has to do with the assumption that people are trying to increase or even maximize their satisfaction. Real life tells us that many people—especially people who are poor, insecure, or unhealthy— are less concerned with maximizing satisfaction than they are with minimizing dissatisfaction. When people are very unhappy or unsafe, they are content if they can simply keep their lives from getting any worse. They have little hope of making life dramatically better. As a result, their life strategies are more cautious than those of people who are trying to increase or maximize their satisfaction. They avoid taking risks. Instead of seeking a career that may bring them great rewards, they may seek a job that is secure and "good enough." They may carry this behavior over into a large number of other domains as well and so miss out on a wide range of possible experiences.

We have no information about how many people are trying to maximize satisfaction and how many are trying to minimize risk and dissatisfaction. It seems certain that this book would have to offer somewhat different advice to each of these two groups of people. Therefore, we have tried to strike a compromise. We focus our attention on the first group of people: the satisfaction maximizers. From time to time, we also include advice for people who want to minimize risk instead. But bear in mind that this book would be a different mixture of elements if we had taken the opposite course.

We cannot be certain that we have made the right decisions in focusing on satisfaction, not happiness, and maximization, not minimization. We simply urge readers to beware of our bias in these directions and to keep asking whether the advice we offer here really applies to them, given their own approach to life goals and life strategies.

With these warnings out of the way, we can now proceed with the main story.

Patterns of Variation

In the rest of this chapter we will explore the ways in which desires and satisfactions vary and look at theories about that variation. This exploration has two main purposes. The first is to understand why people want what they do out of life, and why some feel more satisfied than the average person. (In later chapters we will answer similar questions about particular domains of life in greater detail.) A second and more important purpose is to demonstrate that people's desires and life concerns are patterned: They vary in predictable, understandable ways among different segments of the population.

Variations in Time

People's satisfaction with life and their particular desires and concerns vary over time. Satisfaction will depend on the values people hold and the goals they set for themselves. An ambitious work of early American sociology studied how people's values have changed over thousands of years (Sorokin, 1941). Data collected from a variety of cultures showed that major civilizations of the wor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Exhibits

- Preface

- Note to Instructors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Patterns of Desire: Why You Want What You Want

- 2 Patterns of Opportunity: Why You Get What You Get

- 3 Education: What You Want and What You Get

- 4 Career Choices: What You Want and What You Get

- 5 Single or Married: What You Want and What You Get

- 6 Childless or Parent: What You Want and What You Get

- 7 Locations and Lifestyles: What You Want and What You Get

- 8 What You Want and Get: Closing the Gap

- References

- About the Book and Authors

- Index