- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

National Security in the Third World

About this book

For nations of the Third World, national security poses serious dilemmas. Unlike Western nations, less developed countries must balance the complex and often contradictory requirements of socioeconomic and political development with problems of internal stability and the requirements of national defense. For these countries, a concept of national s

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access National Security in the Third World by Abdul-Monem M. Al-Mashat in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Dilemma of National Security in the Third World: The Need for a Cooperative Environment

Introduction

The dilemma of national security in the Third World has to do with how developing nations perceive their security and with the proper policies to achieve it. Scarce resources, poverty, the need for modernization and institution building, popular demand for a voice in government, expectations for respect and personal dignity, and the need for international cooperation are some of the elements of the security dilemma. Another aspect is a nation's involvement in domestic, regional, and international conflicts.

An overview of the foreign-policy orientations of the developing countries discloses that the concern with external issues and the international environment has superseded the concern about domestic policies. In other words, the need for creating a domestic environment conducive to national cohesion and consensus is not a priority, or at least was not a priority at the time of national independence. An integrative social development strategy has been almost sacrificed for the sake of defending political independence and sovereignty, which have had first priority.

The Transition from Political Independence to Economic Interdependence

By the mid-1950s and early 1960s the security of developing nations was perceived in strategic terms, i.e., in terms of national independence and territorial sovereignty. During this era, the Third World was freed from foreign suzerainty. The essential security question was how to maintain independence and sovereignty--the newly acquired national goals. Concerns and fears about external threats and foreign intervention in the internal affairs of the newly emerging nations were overwhelming. Therefore, the regional central powers such as Egypt, India, and Yugoslavia rejected all forms of alignment with any of the superpowers. For instance, Nasser argued that

One of the fundamental aims of Arab nationalism is independence, . . . freedom to make our decisions, freedom to keep outside anybody's sphere of influence. I am against the alignment of Arab countries with any big powers. Such an alignment could open the door for the big power to become dominant and to bring back imperialism and colonialism to the Arab lands (Nasser, n.d.:133-135).

Other Third World leaders expressed their fears that their independence was threatened by neo-colonialism. Nkrumah contended that

Neo-colonìalism acts covertly, maneuvering men and governments, free of stigma attached to political rule. It creates client states, independent in name but in point of fact pawns of the very colonial power which is supposed to have given them independence (Nkrumah, 1963: 174).

Nkrumah's argument was in fact derived from Lenin's insight, when he contended that political independence per se was one of the "diverse forms of dependent countries which, politically, are formally independent, but in fact, are enmeshed in the net of financial and diplomatic dependence" (Lenin, 1977: 104-122).

Fears of foreign intervention were exacerbated by the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. India's Nehru expressed his abhorrence of the Cold War and its psychological ramifications in the following terms:

The cold war means thinking all the time in terms of war; in terms of preparation for war and the risk of having the hot war. The cold war creates a bigger mental barrier than brick walls or iron curtains do. it creates barriers of the mind which prevent the understanding of the other person's position, which divide the world into devils and angels (Das, 1961:218-219).

By the mid-1950s, then, the dichotomy of the world system into competing superpowers and newly independent states began to crystallize. In the prevailing view, security of the "upper dogs" (using Galtung's concept) was perceived in terms of containment, brinkmanship, and alliance building, while security of the "underdogs" was seen in the light of independence, sovereignty, and neutrality.

Security policies in developing nations during this nation-building stage were aimed at avoiding the serious repercussions of such a dichotomy. The creation of an international environment conducive to cooperation and stability was the proper way for these nations to achieve their security aims.

Third World leaders in the 1950s and 1960s argued, in effect, that their nations should take cooperative, neutral stands between the two superpowers. Nasser, for instance, argued that collective cooperation had become imperative in designing the foreign policy of Egypt (The Charter, 1962:97-104). Consequently, cooperation was no longer a classroom word suggesting an ethical but elusive mode of behavior; cooperation had become academically and politically viable and an essential mode of behavior for the "organic growth of the world system" {Mesarovic and Pestel, 1974:110-111).

In order to attain international peace and cooperation, which was perceived as a necessary condition for security in developing nations, these leaders concluded that their nations would have to play a role in the bipolar international system. Therefore, they have pursued three strategies since the mid-1950s: building their military strength, taking a position of nonalignment, and exercising economic power through the formation of the Group of 77.

The Military Buildup in Developing States

National security has always been equated with the military strength of nation-states. Leaders of developing nations were concerned with having an adequate military apparatus to defend their newly acquired independence against external threat or internal insurgence. This strategic perspective was the result of two political facts: (1) a tremendous fear existed that ex-colonial powers would try to regain dominance, and (2) in most developing nations, the military apparatus was the institution to which the ex-colonial powers transferred authority. Consequently, when sociopolitical and structural changes were initiated in the developing nations, usually the military elite were the decision makers. This self-perceived role stimulated the military elite to allocate a large proportion of the national revenues to build up armies.

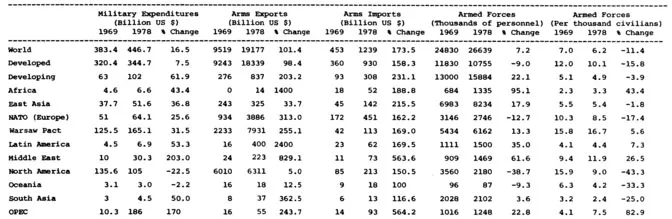

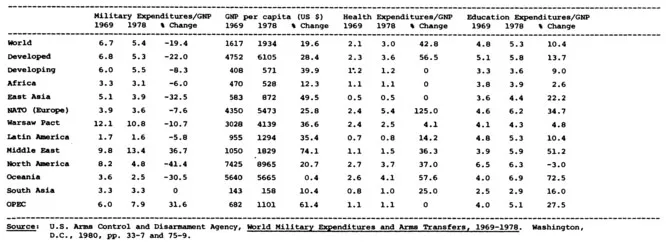

Table 1.1 shows several indicators of the increasing expansion of the Military establishment in the developing nations. First, military expenditures are increasing at a faster rate in developing nations than in developed countries. Much of the 16.5 percent growth in world military expenditures between 1969 and 1978 is attributable to developing nations. During this period, the military expenditures of developed countries increased from $320.4 to $344.7 billion (in constant 1977 dollars), an increase of 7.5 percent, while expenditures among developing nations jumped from $63 to $102 billion, or

Table 1.1 Military and Social Trends: World, Developed and Developing Countries, and Regions, 1969-1978

61.9 percent. Thus, the developing nations have outsripped the percentage increase in developed countries' expenditures on armed forces since 1969. The number of personnel in their armed forces increased by almost 3 million, or 22.1 percent, while personnel in the armed forces of the developed countries decreased by 9 percent in the same period. Armed forces in Africa have almost doubled in size during these ten years (95.1 percent). The Middle East occupies second place in this regard with a 61.6 percent increase, followed by Latin America with 35 percent. OPEC countries have increased their military forces 22.8 percent over the past ten years. Thus, we can see increases in the armed forces of developing nations, but among developed countries (except for the Warsaw Pact nations), armed forces show reduction in number of personnel by no less than 9 percent.

Second, the international arms trade illustrates the upward rate of military expenditures and weapons acquisition of developing nations. Arms imports by these countries increased at a striking rate of 231.1 percent between 1969 and 1978 (see Figure 1.1). The Middle East is the leading region in this regard, with an increase of 563.6 percent between 1969 and 1978. In fact, the Middle East alone accounted for more than one-third of world arms imports in 1978 (see Figure 1.2). OPEC countries in general show a high increase of 564.2 percent (Table 1.1), which indicates a serious trend toward acquiring more weaponry. East Asia, Africa, and Latin America follow the Middle East in increases in arms imports: 215.5 percent, 188.8 percent, and 169.5 percent, respectively.

It is significant that the share of the developing nations in world arms exports is also increasing at a higher rate than that of the developed countries. World arms exports increased from $9,519 billion in 1969 to $19,177 billion in 1978, an increase of 101.4 percent. During this time arms exports of the developed countries rose from $9,243 billion in 1969 to $18,339 billion in 1978, an increase of 98.4 percent, but arms exports of the developing nations jumped from $276 billion in 1969 to $837 billion in 1978, an increase of 203.2 percent. These figures reveal that a doubling of arms exports by developing nations has little effect in increasing world rates, simply because the developed nations have a much greater volume of arms exports. The developed nations control 95 percent of the volume of arms trade, the developing nations only 4 percent (see Figure 1.3). The Soviet Union and the United States alone supply more than two-thirds of world arms exports (34 percent and 33 percent, respectively). If the volume of arms exports of the West European members of NATO is added to that of the United States, then NATO alone accounts for more than half of world arms exports (53 percent in 1978).

Third, there is an increasing tendency among developing nations to produce their own weapons either indigenously or under license. The reasons for this trend are varied and complex, but most significant among them is the desire to achieve independence of foreign suppliers and the pressures that these suppliers can exert over the security interests of developing countries.1 Table 1.2 reveals the increasing number of dev...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 THE DILEMMA OF NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE THIRD WORLD: THE NEED FOR A COOPERATIVE ENVIRONMENT

- 2 NATIONAL SECURITY: FROM STRATEGIC TO NONSTRATEGIC CONCEPTION

- 4 TRANQUILITY INDEX: A MEASURE OF NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE THIRD WORLD

- 5 EPILOGUE

- APPENDIXES

- Bibliography

- Index