![]()

1

The Maturing Metropolitan Water Economies

James E. Nickum and K. William Easter

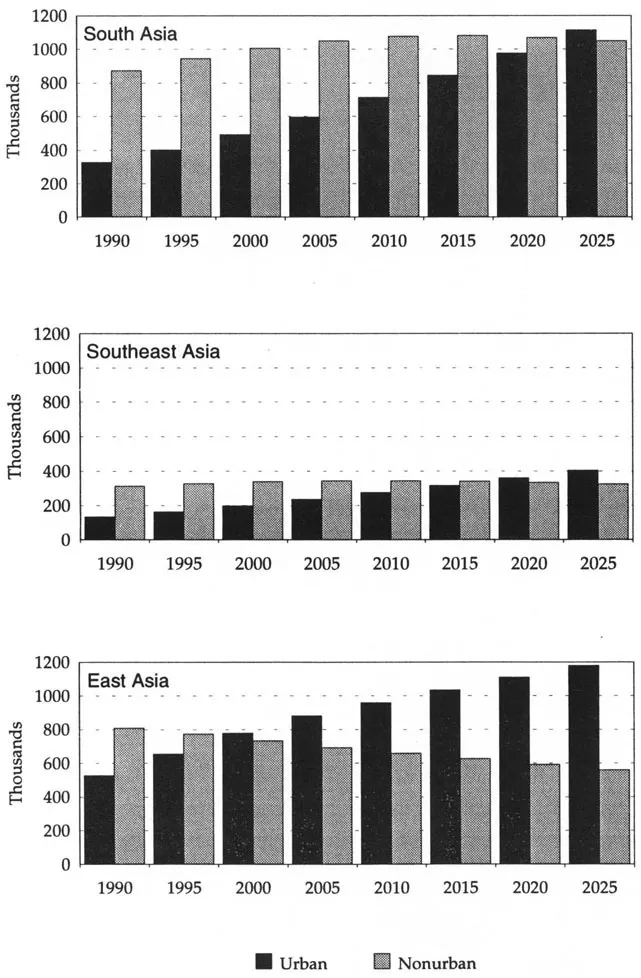

The towns and cities of Asia and the Pacific are big and expanding rapidly. One-half of the world’s megacities are in the region, and “millionaire” metropolises are commonplace.1 Nonetheless, Asia is the least urbanized region in the world in terms of share of population living in cities.2 In part because of this, its rate of urbanization, especially in South Asia, is the highest in the world (see Figure 1.1). Since most of the population in Asia and the Pacific is still rural and increasingly mobile, the stresses of the region’s urbanization are likely to dominate the political, environmental, and economic scene over the coming decades. Prominent among these stresses will be growing conflicts over water.

The growth of cities has intensified urban-rural interactions. Urban areas are drawing more and more heavily on the food, labor and natural resources of the rural sector, while providing the latter with incomes, employment, lifestyle models, and domestic and industrial wastes. Often, these interactions are mutually beneficial. When it comes to water, however, the direct and indirect demands of urban areas on water quantity and quality are leading to pronounced conflicts.

Because one person’s or entity’s use of water commonly affects the quantity and quality available to others, conflicts abound. To use an economic metaphor, water is an excellent vector for externalities. Problems of allocation among water use sectors—agriculture, industry, urban water supply and sanitation, fisheries, navigation, hydropower, environmental preservation, and recreation—are becoming increasingly acute as water resources are more fully used and pollution increases.

The conflict between city and farm is particularly acute in the Asia- Pacific region, where most major cities are surrounded by irrigated

Figure 1.1 Urbanization trends in Asia (data drawn from United Nations 1991:123,125,135,137).

agriculture, a “low-value”" alternative to “traditional"” urban water sources such as groundwater and interbasin transfer, which are becoming increasingly expensive or unavailable. Furthermore, the conflict often becomes critical well before the population of an urban area reaches into the millions, since a significant number of the cities in the region are located in small catchments or on islands.

While intersectoral conflicts such as between irrigation and urban uses of water are increasingly salient, and the main reason we became interested in this problem, they are far from the only problem domain confronting water policymakers. Geographical (upstream-downstream) conflicts between users are still important and are widening in scope as cities reach into other basins for water. Within cities, the problem of serving growing populations settling on extending and increasingly less benign landscapes is laden with strife. In Chapter 2, Y. F. Lee notes a number of sharpening conflicts within the urban water supply and sanitation sector: between tight budgets and high-cost infrastructure, between cost recovery and commitments to provide subsidized“lifeline” services, between system expansion on the one hand and maintenance and repair of existing systems on the other, and between conventional centralized systems and innovative local facilities.

In addition, the conflict between the served and the unserved is salient within almost all use sectors. For example, although drinking water normally constitutes only a small share of total water usage, its quality requirements and direct linkage to health and human well-being have made its provision a central concern of governments around the world. Yet many remain “unserved,” left to less sanitary or more costly alternatives to public provision.

In 1980 only about 40 percent of the world’s population had access to a safe and adequate supply of drinking water. Coverage was lower in rural areas and suburban areas, and for low-income people wherever they lived. It is now clear that, despite immense efforts during the U.N.- declared Decade for International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation, by 1990 only a few countries had reached the Decade’s goal of providing a safe water supply to all their citizens. Between 1980 and 1990 water supply coverage in the world’s urban areas rose from 77 to 82 percent of the population, but was constrained by the rapid increase in the number of city dwellers. In Asia and the Pacific, water supply was extended to 185 million additional residents during the decade, far more than the 148 million remaining unserved in 1980. Yet because of urban growth, urban supply coverage increased by only 4 percent, and the number unserved increased by 27 million, to 175 million. In many cities, even those who are connected to the public supply are not well served in terms of timing, quality, or availability of tap water. The water supply Situation in many cities remains difficult, and may be worsening (Christmas and de Rooy 1991).

Water Shortages

Water quantity problems are accelerating in most Asian-Pacific metropolises because of their growing economies and populations. Although, in general, most population growth in these cities is due to urban births, the worldwide trend toward greater mobility of populations is likely to lead to increasing pressure on cities of rural-to-urban migration. Reductions in rural water supply, if they lead to loss of livelihood, would accelerate this migration. Thus cities will be faced with the question of how to deliver water to an ever-increasing urban population without harming those who remain on the farm.

As metropolitan water authorities try to secure added supplies to satisfy their residents, they compete with other sectors for water and for funds. This is reflected in a rapid upsurge in the long-run marginal costs of supply in cities around the world (Munasinghe 1992:13–15). Competition for budgetary allocations will intensify as more funds are requested for improving water treatment facilities, replacing leaky pipes, or developing new surface or groundwater supplies. All these activities cost money,3 yet in most areas users have not been paying the full cost of their water supply. The larger the subsidy involved, the more government funds will be required to keep up with growing demands.

If the primary source of water for a city is a surface flow, competition will extend up and down the stream. How well each metropolitan area does in this competition will depend on the rights structure and water policy at the national and local levels. Which sector has the highest priority rights to water: domestic, industry, agriculture, recreation, or hydropower? In some countries the ranking is spelled out, almost always giving first priority to domestic users.4 In other countries priorities are not spelled out.5 In ordinary times, a first-in-use (e.g., appropriationist) principle is usually applied, although it is often difficult to control subsequent upstream uses, especially but not exclusively their degradation of downstream water quality. Multiple purpose reservoirs often allocate water based on a preset rule. In most countries, ad hoc adjustments are necessary in the face of droughts. These adjustments are commonly made by representatives of the various user agencies. In Japan, water rights (suiri ken) are effectively suspended during water shortages.

This causes a great deal of uncertainty for a metropolitan area and may encourage it to claim supplies well in excess of current needs. Since weather has an immediate effect on surface water supplies, water scarcity within many metropolitan areas is likely to occur on occasion unless the supply is unusually large. Even those Asian metropolitan areas in the monsoonal tropics have to deal with dry season shortages. The important trade-off in these cases is the cost of investment in excess or reserve supplies versus the losses due to water shortage.

The water shortages will have different impacts depending on how they are exhibited and how the metropolis responds. Scarcity may show up as low water pressure in the delivery system, as restrictions on supply for short periods during the day, as cutbacks in service to certain areas of the city, or as quantity restrictions on each household or on certain activities. The biggest economic losses occur in extended periods of scarcity if industry (including hydropower) does not get water, although, in agriculture, an entire crop may be lost if water is unavailable during brief critical periods; households may face significant cost increases if they must turn to expensive alternatives to public supply. They may also have large “noneconomic” losses imposed on them when their health risks increase due to reduced use of water for sanitation.

Frequent water shortages, or unreliability or absence of public supply, may impel some users to provide their own water through wells. This can lead to an overdraft that allows saltwater intrusion or irreversible compaction of the aquifer. The result may be loss of a valuable resource for the metropolitan area.6

Water Quality

In general, the basic concepts that apply to conflicts over water quantity may be used for water quality as well, although the latter is usually more complex due to the larger number of quality dimensions. Sometimes the two are somewhat directly related. The phrase “the solution to pollution is dilution” was once commonly accepted. If the supply of water goes down, the concentration of a fixed input of pollutant will go up. A common strategy for pollution control is to increase water supplies during low flow periods. This does not work very well if there is a severe drought, however, or if for other reasons there are alternative demands on flushing water. It also cannot be applied to certain toxic pollutants with no threshold effect that tend to accumulate in sediments and biota.

Besides acting as a vector for externalities, water is an excellent medium for disease vectors and toxic materials. Four-fifths of all illnesses in the developing world have been associated with unsafe and inadequate water supplies and sanitation (USAID 1987: 23).7 Urban, and increasingly rural, industries may damage the countryside’s water supply through the discharge of chemicals. “Modem” pollutants such as chemical fertilizers and pesticides from farms may degrade the urban water source, as may more traditional sources such as manure and sediment, which tend to increase with economic development.

“Non-point source” pollution from farms and households is often harder to control than industrial discharges. Sometimes, especially with pesticides and organic wastes, farmers damage their own water supply, because of lack of awareness or training and improper or inadequate labeling of chemicals. Lack of alternatives and low incomes, together with the ...