eBook - ePub

Metropolis And Nation In Thailand

The Political Economy Of Uneven Development

- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This qualitative study of the relationships between one primate city, Bangkok, and its hinterland, the Thai nation, breaks new ground in general sociological theory, redirects the study of city-hinterland relationships, and presents an interpretation of Thai political history that departs significantly from conventional analyses. Professor London f

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Metropolis And Nation In Thailand by Bruce London in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Metropolis and Nation: Theory and Research

The study of metropolis and region has a long tradition in human ecological and urban sociological studies of “developed” countries, especially the United States. This research tradition dates back at least to the work of Gras (1922), and has been carried towards the present through the efforts of McKenzie (1933), Bogue (1949), Hawley (1950), Vance and Smith (1954), and Duncan, et. al. (I960). Until somewhat more recently, however, much less attention had been paid to city-hinterland relationships in “developing” countries. Considerable interest in the cross-cultural study of urbanization was generated by a short essay by Gideon Sjoberg (1959), and by the benchmark volume published by the Social Science Research Council Committee on Urbanization (Hauser and Schnore, 1965). One result is increasing attention paid by sociologists, geographers, planners, and others to city-hinterland relationships in developing countries. Although not always couched in terms of “city-hinterland relationships,” those studies which focus on the relationship between city-size and economic development (Berry, 1961, 1971; Berry and Garrison, 1958), on urbanization and regional or national development (Friedmann, 1966, 1973), on the geography of modernization or the orgainization of space in developing countries (Gould, 1964, 1970; Soja, 1968; McNulty, 1969; Johnson, 1970), on growth poles and growth centers (Kuklinski, 1972), on uneven development (Cornelius, 1975), or, in certain cases, on internal colonialism (Walton, 1975) — are all concerned, either implicitly or explicitly, with assessing the impact of different levels of urbanization (in terms of the number, size, and spatial distribution of cities) on hinterland, and ultimately, given the nature of the case, national development (Keyfitz, 1965; McGee, 1971).

This entire literature takes as its starting point the frequently observed divergent descriptions of city-size distributions in developed as opposed to developing countries. In contrast to the well-developed systems or hierarchies of functionally interdependent cities ranging along a spectrum of sizes found in most Western industrial nations, many underdeveloped nations are characterized by urban primacy: the existence of one overridingly large city which dominates the nation functionally as well as in terms of size. Several researchers have argued that particular types of city-size distributions - polarized in terms of urban hierarchies on the one hand, versus primate cities on the other - are related to specific stages of development. Implicit in this observation is the idea that primacy retards national development in general and results in uneven regional development (i.e., severe regional/spatial inequalities) in particular.

Little explanation of why this should be true, however, has been forthcoming. Primacy may well be correlated with low levels of development; but, this descriptive regularity notwithstanding, exactly what effect does the primate city have on its hinterland (i.e., the entire nation), and how can this effect be “measured”?

My approach to these questions will be to (1) criticize earlier efforts, (2) suggest alternative approaches to the examination of these issues based on those criticisms, and (3) test the relative efficacy of these alternatives as applied to a case study of Thailand. In brief summary, then, the aims of this research are first, to generally extend the comparative knowledge of city-hinterland relationships, and, more specifically, to assess the impact of a primate city, Bangkok, upon its hinterland, the Thai nation.

Is the Primate City Parasitic? The Traditional, Demographic-Ecological Approach

An intersection of interests in urban ecology and the study of developing areas leads almost inevitably to a consideration of the primate city concept. This “law”, formally introduced by Mark Jefferson (1939), refers to the relationship between size and function of the largest city in a country and the other cities in the same country.

The primate city concept has received only limited attention since its inception. Recent discussions of primacy seem to converge on two related, but distinguishable issues. First, attempts have been made to delimit the correlates of primacy; or, in other words, to examine the relationship between degree of primacy and certain socio-economic, demographic, and ecological characteristics such as per capita gross national product, level of economic development, population density and distribution, and so on (Mehta, 1969; Linsky, 1969; Owen and Witton, 1973; Vapnarsky, 1969; El Shakhs, 1972). Secondly — and this is the issue to which the bulk of my efforts will be addressed - there is a concern with the validity of the frequently repeated (Hoselitz, 1955; Lampard, 1955; Hauser, 1957) view that the primate city is “parasitic” rather than “generative” (Mehta, 1969; McGee, 1971). Those researchers who view the primate city as parasitic are, in effect, bringing the findings of the research on the correlates of primacy to bear upon a study of the question of the effects of primacy. In general, primacy was found to be characteristic of small countries having low per capita incomes, highly dependent upon the exports of an agricultural economy, and experiencing rapid growth (Linsky, 1969). Although there are exceptions, these characteristics, and the primacy correlated with them, are common to the so-called “underdeveloped countries” (Owen and Witton, 1973; El Shakhs, 1972).

Herein lies the source of the argument for parasitism. It is just a short step from contrasting those highly developed primate cities with their underdeveloped hinterlands1, to assuming and asserting that it is the primate city that actually creates and perpetuates uneven development by acting as an obstruction to hinterland economic growth. A number of other variables are incorporated into the several slightly varying definitions of parasitism. All of these may be subsumed under an over-riding concern with a sort of blockage of national development. They include (1) retarding the development of other cities and being oriented primarily to the provision of goods and services to either foreign or indigenous elite markets (Hauser, 1957: 87); (2) the dissipation of the profits of primary pursuits on urban amenities (Lampard, 1955:131); and, as a sort of counterweight to an overemphasis on exploitation of the hinterland, (3) an awareness that parasitism may also take the form of totally ignoring the hinterland (Stolper, 1955:141).

In addition to these explicit discussions of primate city parasitism, there is an implicit discussion in Andre Gunder Frank’s thesis of the dialectic relationship between capitalism and underdevelopment (1967, 1969). Here the primate city is viewed within the context of an international rather than solely a national setting. Indeed its parasitic effect on the hinterland is understood as a result of its dependent ties to the larger world-capitalist system. The primate city is no longer the dominant, but the intermediary -at once exploiter and exploited. In Frank’s (1969:6. Emphasis added.) terms:

… these metropolis-satellite relations are not limited to the imperial or international level but penetrate and structure the very economic, political, and social life of the (dependent)… colonies and countries. Just as the colonial and national capital and its export sector become the satellite of the… metropoles of the world economic system, this satellite immediately becomes a colonial and then a national metropolis with respect to the productive centers and population of the interior. Furthermore, the provincial capitals … are themselves satellites of the national metropolis — and through the latter of the world metropolis … we find that each of the satellites… serves as an instrument to suck capital or economic surplus out of its own satellites and to channel part of this surplus to the world metropolis of which all are satellites.

Although Frank does not couch his analysis in these terms, and although his approach can hardly be considered “traditional”, it seems appropriate to equate his national metropolis with the parasitic primate city — a conclusion supported by Vapnarsky’s (1969) suggestion that primacy increases as “closure”, or the degree of national self-sufficiency in an international context, decreases.

The evidence therefore points to a correlation between primacy and indices of regional and national “underdevelopment.” Implicit within the various descriptions of this empirical regularity, however, and bearing directly upon the issue of “parasitism”, are several possible alternative causal mechanisms. The first of these “explanations” of primate city parasitism, reflected particularly in Vapnarsky’s (1969) concept of a “lack of closure”, is based upon a situation of colonial exploitation. Typically, the main port or capital city in a colony becomes the locus of colonial administration. The most efficient means of exploiting the primary products of the national hinterland was to concentrate all the necessary political and economic functions in this one central place which, as a result, grew to dominate the entire nation by effectively precluding the development of other centers and regions. A variation in this process, focusing on intra- rather than international dynamics, revolves around a conception of internal exploitation in which a primate city exploits its hinterland for its own ends, rather than for those of some external colonial power. These two variants may be combined into a single, two-stage explanatory model such as Frank’s (1969) which analytically separates indigenous and international levels while still asserting that the two are inextricably related empirically.

While there is no unequivocal statement in the literature that primate city parasitism does not exist, there are suggestions that the case for parasitism has been overstated (Mehta, 1969). A misplaced emphasis on parasitism may obscure what generative tendencies do exist, as well as deny the possibility that primate cities may well prove to be generative in the long run (Hoselitz, 1955; Owen and Witton, 1973). Indeed, El Shakhs (1972: 30-31) asserts that the relationship between primacy and underdevelopment is curvilinear:

Beginning with the rise of cities amid dispersed and isolated subsistence settlements, population growth, developments in technology and the economic means of production, and shifts in the distribution of authority tend to centralize and concentrate nonagrarian functions and populations in cities. In a system of cities, this centripetal process of concentration shifts steadily, and at an increasing rate from a local to a regional to a national scale, at which time most of the urban functions and services, political and economic power, and population become centralized and concentrated in one or a few core areas (or primate cities) which have acquired an unusual capacity for serving as centers of innovation. It is at this stage that regional inequalities and differences are intensified, the primacy curve reaches its peak, authority patterns are challenged, and conflicts over the patterns of authority and development begin to sharpen… Eventually, with the increasing influence and importance of the periphery and structural changes in the pattern of authority … deviation-counteracting processes induce a decentralization and spread effect in the development process. The economy drives toward a full utilization of its undeveloped resources, and interregional growth patterns tend to become more balanced through the rapid growth of the less developed regions and their urban centers.

In other words, because most studies of the relationship between primacy and underdevelopment are cross-sectional, the finding that the two are positively correlated is not unexpected. A longitudinal analysis, however, if based on a sufficiently lengthy time period, may reveal that primacy is indeed a sort of “necessary” intermediate stage through which national urban systems tend to progress. In other words, the urban decentralization so highly correlated with balanced regional and national development and, therefore, so sought after by Western planners, geographers, economists, et. al. (Johnston, 1970), may be achieved in many nations only after a period of primate centralization and concentration and spatially-limited but potentially dispersible development (Keyfitz, 1965). As Berry (1971) and Friedmann (1972:36) put it, urban systems tend to evolve from a distribution marked by many small, equally-sized central places through primacy to an eventual log-normal (developed urban hierarchy) distribution. In this sense, the primate city may well prove to be generative in the long run, and primacy and underdevelopment may decline reciprocally.

The issue, then, becomes one of attempting to indicate whether or not primate cities (at particular stages in their histories) have a deleterious effect on their regional and, ultimately, national economies. Is the primate city parasitic? Or, are those who view it as parasitic guilty, on the one hand, of assuming that correlation implies causation or, on the other hand, of allowing their ideologies to engender inadequate theories? In either case, focusing on one aspect of reality excludes the other.

To my knowledge, only Mehta (1969) has made an explicit attempt to answer these questions.2 His results are inconclusive. Using standard demographic, ecological, and socio-economic indices, what evidence he does find to support “the parasitic effect hypotheses” is in the predicted direction but it is not statistically significant. The reader is left with the ambiguous assertion that ‘little or no inference can be made regarding the ‘parasitic’ or ‘generative’ impact of ‘primate cities.’” Mehta’s findings and conclusions are somewhat lacking because of a failure to analyze the distinction between those primate cities in developing countries and those in developed countries. In other words, grouping all primate cities together, although it does give us information about the primate city, clouds the issue of parasitism, for it is precisely with reference to some “level of economic development” that the concept of parasitism is dealing. At any rate, there is much room for improvement in this literature. If one still wants to know what effect exceptional primacy has on a nation, then a theoretical and/or methodological alternative to the traditional, demographic-ecological approach must be found.

Is the Primate City Parasitic? The Emerging Political-Economic Approach

In recent years, an alternative to the traditional approach has begun to be formulated. Its initial insight is that, in essence, trying to determine the effect exceptional primacy has on a nation is an attempt to illuminate one facet of the systematic relationships between urbanization and national development. According to Safier (1970:35), such a task may be undertaken by using “a ‘developmental’ approach to the economics of urbanization.” In this regard, most of his discussion “concerns itself with the economic efficiency of the urban system as defined by the ratio of costs to benefits in relation to overall economic growth and structural change” (1970:35). This approach leads Safier (1970:38-43) to delineate three “levels” of analysis which serve as a framework for categorizing the possible relationships between urbanization and development: the economics of the urban sector at the national level, the economics of urban distribution at the sub-national level, and the economics of urban accomodation at the local level.

Expanding upon Safier’s (1970) statement, Gugler and Flanagan (1977:273) argue that, if “economic efficiency” is lacking at any of these three “levels”, severe inequalities (and negative consequences for development) will appear. These include:

- (1) the imbalance in life chances between the urban and the rural sectors,

- (2) among cities, the concentration of the extremely limited resources in the capitals, and

- (3) within cities, the economic disparity between the masses and a tiny elite.

Each of these inequities reflects the potentially negative impact of the “urban system” on national development. Urban-rural sectoral imbalances and urban elite-mass gaps are recurrent phenomena in most Third World countries regardless of the “shape” (rank-size or primate) of the urban system. The concentration of resources in capital cities, however, refers specifically to urban primacy. Therefore, only where urban primacy exists can each of the potential inequities of the urban system be present simultaneously. One may not, of course, assert that urban primacy causes these inequities; it may be suggested, however, that, if the primate city is parasitic, then each of these negative consequences for development will be prevalent where this particular pattern of urbanization exists.

Safier’s analysis is couched in specifically economic terms. He questions whether the pattern of urban growth either produces maximum benefits or imposes minimum costs on social and economic growth in such a manner that growth will eventually become self-sustaining (1970:38). The argument may be made, however, that political factors (e.g., the control of decision-making) are at least as important as economic factors in the development process, especially where the power to control decision-making is centralized in a primate city (Friedmann, 1972:9 and 1973:74-76, 83). Indeed, both Sailer (1970:35) and Gugler and Flanagan (1977:273, 281-285) recognize the latter possibility.

This insight has a direct bearing upon the present definition of the problem - a bearing which must be elaborated with specific reference to the meaning of primacy. I implied above that there are two “dimensions” of primacy, a size dimension and a functional dimension. On the one hand, a primate city is much larger than the second largest city in a nation (Linsky, 1969). Within its boundaries lives an unusually high percentage of the nation’s urban population (Mehta, 1969; Ginsburg, 1961). On the other hand, a primate city dominates a nation functionally. It is the political, economic, social, and cultural-symbolic center of the country.

I argue here that both dimensions must be present for a city to be meaningfully labeled primate. This point requires some elaboration.

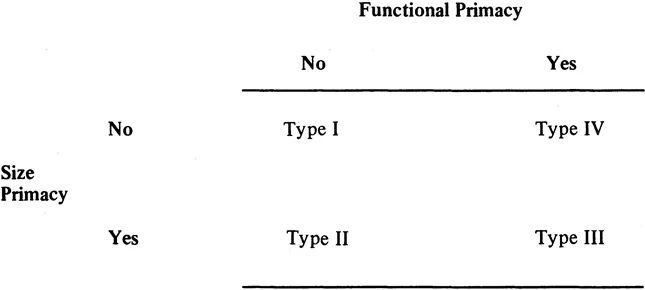

Let me, for strictly analytical purposes, dichotomize each dimension of primacy. Any city either is or is not primate in terms of both size and function. An intersection of these dimensions yields four logical possibilities (see FIGURE 1.).

Type I cities are clearly not primate; they have neither of the defining characteristics of primacy. Type II cities are primate in statistical terms only. I am not, however, able to think of any specific cities which are primate in terms of size but not function. In other words, “functional primacy” would appear to be a universal concomitant of “size primacy.” Type III cities are, of course, primate by definition.

It is Type IV cities that are problematic to this analysis. A city may dominate a nation in functional terms without being statistically primate. The two dimensions of primacy do not stand in a strictly determinate relation to each other. This fact gives rise to an interesting question: Is it justifiable not to label a Type IV city primate?

Jefferson (1939) recognized this issue in his initial formulation.

Figure 1. A Typology of Cit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Metropolis and Nation: Theory and Research

- Chapter 2 The Statistical Primate City: Bangkok, Thailand

- Chapter 3 The Political Primate City: The Distribution of Power in Thai Society, 1850-1973

- Chapter 4 The National Implications of Central Decision-Making: The Policy and Politics of National Integration

- Chapter 5 The Regional Implications of National Decision-Making: The Policy and Politics of Regional Management

- Chapter 6 The Meaning of Parasitism: Social Class, Political Power, and the Ecology of “National Unity”

- Notes

- Bibliography