Agriculture in the Third World has frequently been denounced as barbarous, primitive and wasteful in its use of resources. It has, however, not lacked its apologists or its defenders, who have explained existing practice in terms of responses to environment learned over generations or in terms of social and economic constraints, and who have warned of the dangers of upsetting existing agricultural systems through agricultural ‘improvement’. Whilst the first view tends to assume that a scientifically based agriculture of a kind associated essentially with the industrial nations of Europe or North America must be superior in any situation, the second tends to make sacred any apparent achievement of general environmental and economic equilibrium by an agricultural system and may inhibit change even where change is both possible and desirable. The agricultural improvers share with some theorists of ‘modernization’ schools in economics and geography a general view that the latest innovation must spread everywhere that is environmentally possible or, as Thünen described the situation in 1826: ‘An ancient myth pervades our agricultural writings: that whatever the stage of social development, there is one valid farming system only—as though every system that is more simple, every enterprise that adopts extensive methods to economise on labour, were proof of the practising farmer’s ignorance’ (Thünen-Hall, 1966, p. 258).

Thünen’s originality was not the recognition of a relationship between farming practice and distance from market or farm-stead, but the recognition of a dynamic situation in agriculture in relation to market and the development of a simple apparently static model to describe it. Thünen’s rings are innovation rings and his model implies not only locational differentiation of farming but a spatial pattern of change. Thünen never envisaged that in reality the zones would be circular and that innovation would always move outwards. Such appearances are properties of the model designed in this manner for the sake of simplicity. Nevertheless contiguity is clearly an important element in the dissemination of information, as is also the sharing of common information-spreading networks such as a telephone system or news media organization such as Reuters. As a result many innovations have tended in practice to spread outwards. A new practice belongs, however, to the socioeconomic environment in which it was created. It must solve a particular problem and can be spread only in so far as there exist over a large area similar socio-economic environments or environments in which there are related problems for the solution of which the innovation may be adapted. British mixed farming systems would be as unsuitable in the Brazilian highlands or coastal lowlands as the fazenda systems would be in Britain. In the process of diffusion an innovation may change its form considerably, as, for example, in the development of large-scale plantation systems of production in the Third World. These in one sense may be regarded as the introduction of techniques of European origin, but in another sense are an innovation different in character from any large-scale agricultural practices ever found in Europe (see pp. 72–4). Modernization may and often does assume peculiar forms in those areas of the Third World most open to European or North American penetration.

The World Agricultural System

Peet (1969) has summarized and developed ideas of a world-scale agricultural zonal system (Chisholm, 1962, pp. 189–90) focused on ‘world metropolis’ (Schlebecker, 1960) and spreading outwards, so that an agricultural frontier has been created which invades continental interiors as the outer boundary of a dynamic system whose movements are explicable in terms of changes in internal supply and demand. This world agricultural ‘system’ is, however, not the simple structure suggested by the notion of world metropolis, but a highly complex set of markets and of economic distribution and production systems, in which in the most developed economies almost all agricultural produce is distributed through centralized markets, whilst in the least developed economies most agricultural produce is consumed by the farmers themselves and their dependants. The world ‘system’ has not one but many centres of demand and input supply, each of a somewhat different character and subtending different trading areas. Growth has not only spread outwards but has increased the number of centres and the complexity of their trading relationships. In the most developed economies increased agricultural production has mainly been achieved by intensification and has frequently been accompanied by a decrease in the area under cultivation. In the least developed economies increased agricultural production was the product until 1966 of increases in the area farmed, and even since then increased production through higher yields achieved by greater inputs has been characteristic of only a few countries with especially favourable conditions for the planting of high yielding varieties of wheat, rice and, to a lesser extent, maize and sorghum. In the rice producing regions, especially, most of the production increases achieved before the introduction of the ‘new seeds’ were associated either with shifts in the regional distribution of the area devoted to rice or with modification of the environmental factors (Ruttan, 1968). Generally in the Third World the level of agricultural technology and the factor proportions in agriculture, despite considerable effort to improve productivity, have remained relatively constant and have tended to increase mainly in proportion to the increase in the agricultural population and in the workforce available as additional land has been brought into cultivation (McPherson, 1968). In very broad terms a real contraction has occurred at the ‘centres’ of the world agricultural system and expansion at its periphery. A remarkable feature of the Third World has been the mobility of its rural settlement and the speed with which transport and trade infrastructures have been extended to cope with the increased area under commercial crops. These changes are not, however, necessarily indicative of peripheral vigour in agriculture. On the contrary, peripheral expansion has often been the result of a general lack of innovation or of limitation in the effectiveness of current agricultural innovations in the economic and physical environments of the Third World. In some instances gross overcrowding, as in Bangladesh or in the Ganges Plain of India, has made areal expansion impossible, but even in these areas, apart from the introduction of high yielding crop varieties, little innovation of importance has taken place, and periods of famine have been relieved by the import of food grains from more developed countries. The Third World has thus suffered from its peripheral position, and the major agricultural innovations that have succeeded there have been for improvements in the production of industrial crops for the expanding markets of the more developed countries. The demand for these has proved much more elastic than the demand for food in the less developed economies, despite the generally agreed need for increase in both the quantity and the quality of the latter. In the more developed countries agricultural production has concentrated mainly on the needs of regional or national markets, more especially for food crops. Some countries, such as Denmark and Ireland, have specialized in satisfying certain food demands of other more developed countries. Related forms of agricultural production have appeared at the apparent periphery of the world agricultural system in Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. But the absolute geographical relationships are deceptive, for these countries provide broad environmental analogues of the temperate conditions characteristic of most of the more developed world. They have provided outlets for European emigration and have been favoured by relatively high levels of capital investment. The real periphery is not here, but almost entirely in the tropics and sub-tropics.

The Tropical World

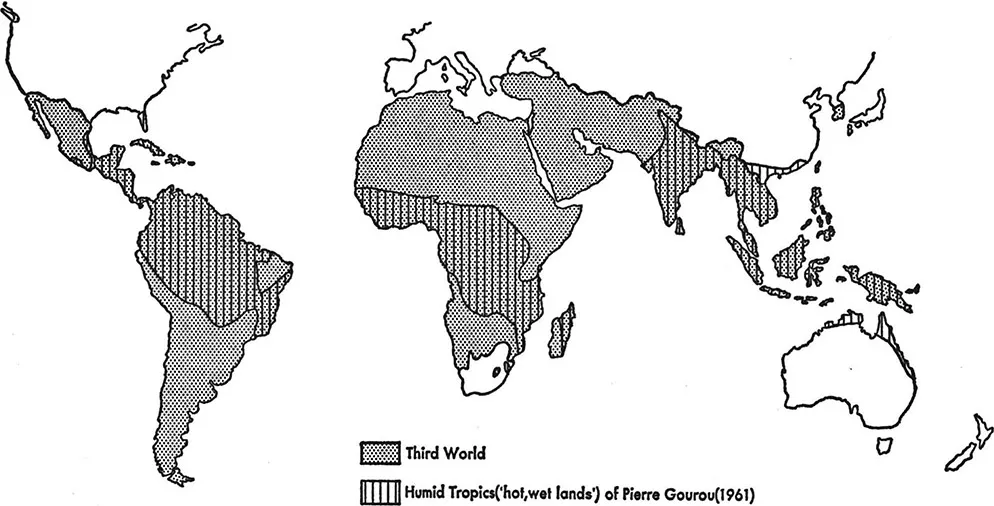

Much of the Third World is tropical (Fig. 1); that is, it is frost free, has only small variations in the length of day, has seasons defined by water availability rather than by temperature,

Fig. 1 The Third World and absence of frost

possesses some distinctive soil characteristics, more especially high levels of mineral accumulation in soil, combined with rapid leaching of nutrients, and for the most part has special difficulties of disease, pest and weed control. Seers and Joy (1971, pp. 78–9) have criticized the ‘optimistic’ view that the geographical coincidence between low levels of economic development and tropical environments is largely fortuitous. Clearly there is a relationship, but this does not mean that tropical environment is a cause of poor development. The tropical world has suffered from lag in the diffusion of appropriate innovations, the concentration of most innovation potential in temperate countries, and distant location both from innovation sources and from major markets, which has helped to reduce profitability and discourage enterprise. It is not that very hot or never cold conditions are particularly difficult for agricultural innovation, but rather that the attractions of the market for agricultural equipment and materials, such as fertilizers and pesticides, have been so much less in tropical countries that few attempts to overcome the difficulties have been thought worth while. Moreover, the problems of temperate agriculture have been more concerned with labour saving and with location-specific problems such as soil nutrients and weed and pest control. Many tropical countries have tended to be labour rich in general terms, although often with local shortage of labour arising from structural problems (see pp. 26–7), and have suffered more from constraints of capital or, less generally, of land. Again the main impetus to agricultural development has come from overseas markets, and these have fluctuated enormously in the prices offered for tropical produce, whilst temperate foodstuffs have frequently enjoyed protected or guaranteed markets. The most attractive sector of agriculture in tropical countries in production potential is subject to enormous risks. The degree to which people from overseas have been willing to invest in tropical agriculture or local farmers have been willing to plant new crops has frequently been astonishing, given the risks involved. Only high levels of reward, frequently coupled with low labour and land costs, have made such development possible (see pp. 93–106).

For Pierre Gourou there is a distinct regional entity, the humid tropics (Fig. 2), which is seen to consist almost entirely

Fig. 2 The Third World and the ‘hot, wet lands’ of Pierre Gourou

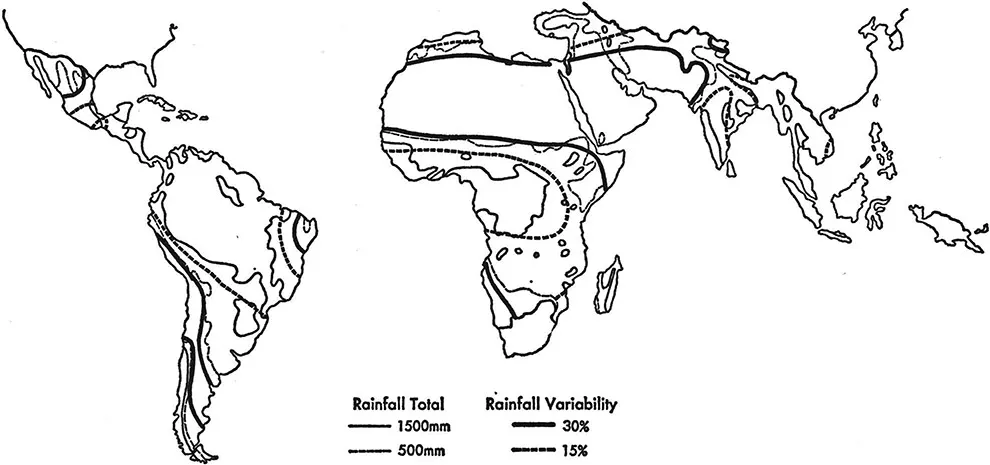

of under-developed countries, which possesses a ‘characteristic agriculture’ and which has its own special physical and human geography (Gourou, 1961, pp. 1, 5 and 25–34). Ίn all hot, wet regions the cultivator has found the same solution for the problems set him by the soil. Universality in space goes hand in hand with universality in time. Europeans in Brazil employed the same methods as the Amerindians, the Africans, the Indonesians, or the Melanesians’ (Gourou, 1961, p. 25). A simple deterministic argument of this kind is not without its force, but the locations cited possess affinities not only of temperature and moisture supply but also of economic development. The ‘same solutions’, which appear to be forms of shifting cultivation, have appeared in non-tropical locations and other forms of agriculture have succeeded in hot, wet regions. The term ‘tropical agriculture’ has found a universal acceptance hardly justified by the facts, as has the notion of a distinctively tropical geographical region. There are few agricultural enterprises or particular forms of agricultural practice which belong exclusively to a region which may be defined as tropical, just as there are almost as many definitions of a tropical region as there are geographers who are interested in making such a definition. Gourou took as his criteria a mean monthly temperature of at least 18.3°C and a minimum rainfall of 610 mm a year, which he thought to be enough for agriculture to be possible without irrigation. Waibel, regarded by some as the founder of modern agricultural geography (Manshard, 1974, p. 2), proposed the much broader and more economic definition of the tropics as an area in which we find mature, economically valuable plants which require much heat (Waibel, 1937, p. 19), but this definition lacked precision, and many annual crops needing high temperatures can be produced in areas where the high temperatures required exist for only a short time but sufficient for their vegetative period (Manshard, 1974, p. 8). Other definitions include those of Gamier, who suggested at least 8 months with mean monthly temperatures of 20°C or more, mean relative humidity of at least 65 per cent and a minimum period of 6 months with mean vapour pressure 20 mb. or more, and of Küchler with his vegetation-based ‘more or less permanently humid’ tropical rain forest zone and ‘more or less periodically humid’ semideciduous forest zone, together with deciduous forests with relatively few epiphytes and/or savannas (Fosberg, Garnier and Küchler, 1961). There is no generally acceptable ‘tropics’ or ‘humid tropics’. As Fosberg showed, views have tended to be so far apart that any solution to the problem of regional definition would be purely arbitrary. Convenience with regard to the definition of a hot, humid area related to the facts of agriculture suggests a preference for Gourou’s more practical approach, allied to the notion, echoed by Küchler, that in the tropics ‘everything which is not arid must be humid’. Accordingly for this purpose the humid tropics may be distinguished as the zone in which there is sufficient moisture supply for a rain-dependent agriculture without irrigation or resort to dry farming techniques. In practice the zone needs at least three months rainy season, the shortest growing period for the fastest maturing cereals, mainly varieties of pennisetum millet or eleusine. Limiting average rainfall totals are for the most part about 500–600 mm, although in areas of high rainfall variability higher average totals are often regarded as reasonable minima. In East Africa, for example, 760 mm has been estimated as the minimum annual requirement for cereal cultivation (Glover, Robinson and Henderson, 1954; Grigg, 1970, pp. 235–6). Rainfall variability and crop failure rate increase dramatically as rainfall totals decrease (Fig. 3). This zone may be divided into a sub-zone with varying lengths of dry season significant for agriculture and a constantly humid sub-zone which includes not only the areas with rain in every month, but even those areas with up to approximately two months ‘dry’ season with very high relative humidity and frequent occurrence of morning dew, often in amounts vital for plant growth. The zone also includes very large areas of irrigated and floodland agriculture.

There are several features sufficiently peculiar to agriculture in the humid tropics to be regarded as distinctive, although most of the more salient characteristics either occur elsewhere or are differences of degree rather than of kind. Distinctive features include:

- The use of shading devices or large leaved inter-cropped shading plants such as cocoyams or bananas. For some tree crops this may take the form of a long-term succession of different shading plants providing broad leaves at different

Fig. 3 Rainfall. Distribution and variability in the Third World

heights. Care has to be taken as over-shading can result in weak, thin stems (Jacob and Uexküll, 1960, pp. 84–5).

- Rapid growth of self-sown plants including weeds and fallow plants. Some agricultural systems incur bottle necks in weeding during the growing period, others in clearance of fallow before planting (see below, p. 27).

- High risk associated with variability in moisture supply. Highly variable rainfall occurs outside the tropics, but has a special significance in the tropics in that moisture and not temperature is the principal growth constraint. Risk avoidance techniques include production diversification and extension of the planting and harvesting periods.

- High incidence of pests and diseases, especially diseases carried by insects. The lack of a winter break frequently exacerbates the problems. Some pests are associated with a variety of host plants, enabling them to establish themselves in a succession of plant environments in areas of marked seasonal rhythm. Control can be achieved by careful attention to fallow management and the burning of crop refuse.

- Double cropping is rare in the temperate world, occurring there most commonly in market gardening with a few quick-growing vegetables. In the tropical world it is of common occurrence where the rainy season is nine months or more and sometimes also occurs on irrigated land. Double cropping involves planting a second crop immediately after harvesting the first and in the same location. It is to be distinguished from succession cropping where in the same field a number of crops may be planted and harvested in sequence. In some equatorial areas the constant heat and moisture supply make ‘multi-cropping’ possible, that is a succession of plantings, weedings and harvestings, whose seasonal rhythm is more the product of the life cycle of the plants themselves than of any rhythm of environment.

- A marked tendency to lodging amongst cereal crops liable in hot, humid conditions to exhibit luxurious rapid growth. Optimum nitrogen dressings can in consequence be larger where temperatures are lower, resulting in a tendency for the maximum yields of crops of wide extent in the tropics, such as rice...

Fig. 3 Rainfall. Distribution and variability in the Third Worldheights. Care has to be taken as over-shading can result in weak, thin stems (Jacob and Uexküll, 1960, pp. 84–5).

Fig. 3 Rainfall. Distribution and variability in the Third Worldheights. Care has to be taken as over-shading can result in weak, thin stems (Jacob and Uexküll, 1960, pp. 84–5).