![]()

Part 1

Economics and Government Policy

![]()

1

Information as a Commodity: Public Policy Issues and Recent Research

Yale Braunstein

Introduction

The economist has generally held several different views of information and the role of information in our society. Representative of these views are the role that information plays in the functioning of competitive markets, the understanding of the increasing amount of resources devoted to the production and distribution of information, and the analysis of how more or better information may improve the market position of one or a group of economic "players." This chapter focuses on why information poses special problems for a "market" or "mixed" economy and then suggests some current and possible future solutions to these problems. A taxonomy of information types is also presented with the hope that this specification will present information about information itself, as well as give further insight into the problems information presents to the economist.

Recent research in the macro-economics of information highlights the role of information in today's society. Western industrialized economies are devoting an increasing share of their resources to the production and distribution of services as opposed to the production and distribution of goods. The identification of an "information sector" of our economy can be traced to the pioneer work of Machlup,1 Since that time the information industry has become aware of its own existence-forming an association and publishing newsletters and reports. Researchers have continued to keep economic tabs on the industry: Machlup is now involved in updating and extending his research, and Porat has become identified with the statement that the number of workers in "information occupations" (appropriately identified) now exceeds the total number employed in all other fields.2 These are just two examples of current research in the macro-economics of information.

In studies of both the functioning of markets and the "failures" of markets—both real and potential—economists have identified several characteristics of a market commodity, either a good or service, that may lead to difficulties. Unfortunately, most of these trouble-causing characteristics are precisely those attributes that make information so interesting to study. Information is not the only good or service that has any one of these characteristics, but new technological advances have given rise to new methods of producing, transferring, and storing information so that different "bits" or types of information may have more or less of some of these attributes.

The attributes that describe information and often give rise to market failures include

- Public good characteristics (simultaneity of ownership and difficulty in exclusion)

- Indivisibility

- Nondepletability

- Inherent uncertainty and risk in transaction

The public good characteristics indicate that the same bit of information may be owned by more than one person. Similarly, excluding nonpayers from the benefits of consuming or possessing the information is difficult. Although perceptions of what actually constitute public goods may vary, examples generally include national defense, streetlights, and libraries. With the extension of computerized information systems, we also have the additional problems of privacy, both of the records and of the information. This puts the difficulties of exclusion in a somewhat different and more complicated light. So far the legislative attempts to improve the situation—the Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act—do not seem to have eliminated the difficulties they have addressed.

Indivisibility is a problem that arises in many areas of economics. Although half of an idea may be as useless as half of a tool, both may be available in different quantities. But non-depletability is not an attribute of tools. When I sell you my wrench, you can take possession of it from me. But when I sell you my idea, I still know what it is, and, depending on the agreement between us, I can possibly use it myself or sell it again to another party. This has become a real problem in the information field where there are examples of producers of information competing against their customers for additional buyers.

The inherent riskiness in the purchase of information is related to its other attributes. I cannot be certain of the value to me of a bit of information until I know what it is. In fact, I cannot make an accurate judgment on the basis of part of the information or on information about the information. And, if I did have perfect information about what was being offered for sale, I would no longer need to purchase it.

While these difficulties in the development of markets for information are real, some solutions do exist. The variety of these solutions and the areas in which they have arisen should cause one to ask if a given solution is the most appropriate for the circumstances. A few illustrations will indicate the anomalies that can arise regarding information.

In many cases where it is difficult or impossible to have the competitive production of public goods, the government has either taken over the production or subsidized private production. To the previously cited examples of national defense, streetlights, and libraries can be added the slightly more controversial areas of public schooling (and subsidies to private schools), academic journals and scientific publications, and satellite-provided information (the Earth Resources Technology Satellite, or Landsat). In each of these additional cases, some anomaly in government policy becomes evident. Universal elementary and secondary schooling is supposed to provide an educated electorate as well as aid in the dissemination of information. But subsidies to private schools are limited. The Government Printing Office (GPO) and the National Technical Information Service (NTIS) provide various technical and nontechnical publications, and the government subsidizes academic journals by paying page charges to increase the dissemination of scientific information. But these page charges are only paid to nonprofit publishers. in the Landsat program, the government has launched a complex satellite to provide, among other things, information for improved crop forecasting. The benefits from this program are on the same order of magnitude as the costs. But these benefits may be mostly private benefits, accruing to a few large grain-trading companies, even though the costs were public.3 Here we have the interesting example of a situation where a company needs to have a large investment in the acquisition of information to be able to profitably make use of additional information provided at little or no charge by the government. However, Landsat is also a perfect example of the existence of jointness in the production of information. It may be that the land-use monitoring and pollution monitoring aspects of the program will be more useful to the public than the improved crop forecasting abilities. The project also has a large R&D component. Therefore, the difficulty of computing benefits extends to determining the sum of the benefits from each of the multiple uses.

Let us examine these issues more fully. This is best done by first considering pricing and allocation questions in general, for economists hold that the main reason public policy must concern itself with the production and dissemination of scientific information is that, left to itself, this sector of activity can be expected to suffer from resource misallocation and nonoptimal pricing.

Alternatives in Pricing and Allocation

Starting with the most general type of economic considerations, we can examine the pricing structures that can be expected to apply to a public good characterized by economies of scale. By considering the consequences of these different pricing policies, we shall discover the type of regulatory or market structure that is implied.

The two fundamental issues for public policy in this area are (1) public good attributes in the information dissemination process and (2) the scale economies in the dissemination process. The public goods characteristics were discussed above. Economies of scale arise when, for a single-product firm, the average cost per unit of output declines as output is increased.

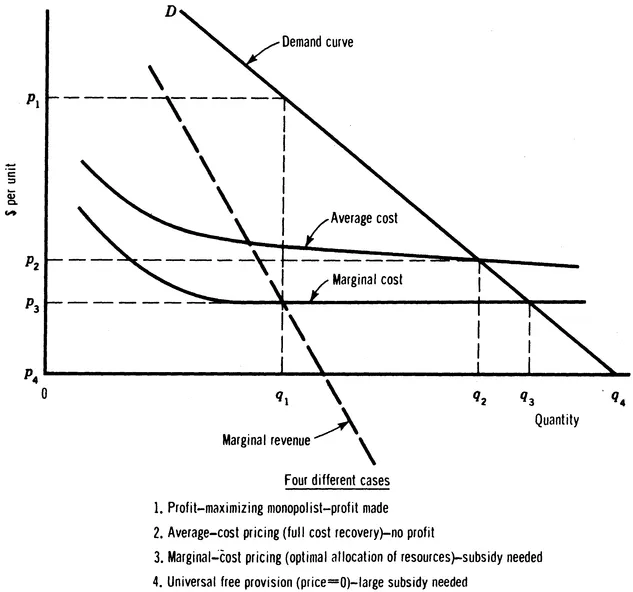

For the firm producing such public goods with economies of scale, there are four interesting pricing "models": perfect monopoly, average cost (AC) pricing, marginal cost (MC) pricing, and free distribution. These four possibilities are listed not only in the order of decreasing price but also in the order of increasing output. The basic problem is that although the usual rule for efficient resource allocation is to have the price of each good or service equal to its marginal cost,

in the presence of scale economies, marginal cost pricing results in a loss for the firm and necessitates a subsidy if production is to be maintained. (Note that the same is also true, to an even greater extent, for free distribution.) The four alternatives are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

The preceding comparison of alternative pricing structures applies not only to information, but to all goods and services with scale economies. One very common illustration of the alternative pricing strategies with their different implications is the case of superhighways. Almost all the roads in California (with the exception of the road around Pebble Beach) have no tolls. On the East Coast, on the contrary, those in charge of the roads often use average cost pricing. Each of these practices implies something very different about the resources one wants to devote to roads and about one's view as to the proper allocation of resources among alternative modes of transportation.

In any of these situations, the pertinent considerations are not quite as simple as the preceding discussion has made them seem. Ingeneral, an optimal allocation requires that the marginal cost of good i be equal to the price of good i for all such goods, as in Equation 1. But this requirement cannot be met by a subsidy if marginal cost pricing is required for every good, because society must raise the money for the subsidy from somewhere—by some form of taxation. And this means that even if before-tax prices are equal to marginal costs, after-tax prices cannot be; therefore the optimal pricing problem becomes an optimal taxation problem. How can the money for the subsidy be raised? The taxes have to be charges on something: a charge on income or on labor or charges on the consumption of various goods, such as value-added taxes or sales taxes. Any type of system of raising this revenue, other than a lump sum tax, causes prices to differ from marginal costs somewhere. And therefore universal marginal cost pricing is impossible. To get around this problem, a modified MC pricing rule must be employed.

FIGURE 1.1: Alternatives in pricing and the resulting operating points on the price-demand curve

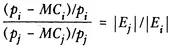

The formula that Ramsey derived for this problem in his pathbreaking paper of 1927,4 which was resurrected and revitalized by Baumol and Bradford in their 1966 paper,5 asserts that there should be a new rule, calling for "optimal departures from marginal cost pricing," that is characterized by Equation 2:

for all i and j, and where Ei is the absolute value of the price elasticity of demand of good i.

In Equation 2 the price for each good should depart from the marginal cost in a way that it is proportional to the inelasticity of the demand for that good. The reason for the inelasticity term is to minimize the quantity effects of these departures from marginal cost pricing, As the price rises, the quantity that gets produced and consumed tends to drop, and Equation 2 minimizes the sum of these quantity effects across all the goods.

Multiproduct Production: The Case of Information

The rule, as stated in Equation 2, applies strictly only in cases where the two...