- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Auditory Development

About this book

This book overviews auditory development in nonhuman species and proposes a common time frame for human and nonhuman auditory development. It attempts to explain the mechanisms accounting for age-related change in several domains of auditory processing.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Early Functional and Structural Development of the Nonhuman Auditory System

Chapter Outline

- Introduction

- Structural Development Prior to the Onset of Hearing

- The Ear

- The Central Auditory Nervous System

- Functional Development and Underlying Factors

- Absolute Sensitivity

- Tonotopic Organization

- Sensitivity in Noise

- Other Response Properties

- Effects of Experience

- Summary and Conclusions

- Notes

Introduction

Auditory perception is determined by the response properties of the ear and the auditory nervous system, which in turn derive from the morphological and biochemical characteristics of individual cells and the connections between them. Changes in auditory perception that occur during development must result from changes in the morphological and physiological properties of these structures. The course of auditory development and its bases in the structure and physiology of the auditory system are the topics of this chapter.

Logically, the morphological and physiological properties of the auditory system during development should provide the basis for predictions about perceptual development. This presupposes, of course, that the relationships between structure and function are well understood in the mature system. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. However, from another perspective, the gaps in knowledge about structure-function relationships in the mature system motivate developmental investigations of these relationships. By examining correlations between structural and perceptual development, one can test hypotheses regarding the role that a given structure or response property plays in perception.

The material in this chapter is derived from studies of auditory system development in nonhuman species, because far more is known and understood about this topic in nonhumans. The major auditory structures, their organization, and their function are remarkably uniform across many species. Thus, we expect that studies of nonhumans will provide information about general principles of auditory development that are likely to be demonstrated in humans as well.

This chapter is meant to provide a general background and to highlight the major events in the development of the auditory system, as well as to illustrate three general points about auditory development, which will guide later discussion:

- Both basic and complex auditory processes develop.

- Many processes that could contribute to auditory development mature concurrently, making it difficult to estimate their independent effects.

- Throughout early development, age-related changes in the structures and functions underlying perception depend on interactions between cells (or organisms) and their environment, both biochemical and electrical. The biochemical and electrical environment may or may not reflect experience with sound.

Structural Development Prior to the Onset of Hearing

The discussion of early structural development is subdivided into peripheral development, the ear and central development, and the auditory nervous system.

The Ear

By the time that any response to sound can be elicited, many of the important events in the structural development of the auditory system have already been completed. Peripheral auditory structures appear quite early in embryonic development. Mice, for example, have a gestational period of about 22 days and begin to respond to sound about 10 days after birth. The undifferentiated cells that will eventually develop into the inner ear are first identified as the otic placode, a disk of cells on the surface of the fetal head, around gestational day 8, The hair cells and supporting cells of the cochlea are "born" between 13 and 15 days of gestation (Sher, 1971). The external ear is first seen as a depression on the side of the fetal head at around 13 days of gestation, and the middle ear ossicles can first be identified at 11 days of gestation. The major events in the development of the subdivisions of the ear are similar in birds and mammals.

External Ear and Middle Ear

The middle ear cavity forms as an outgrowth of the pharynx, which grows toward the surface of the head. A group of "precartilaginous" cells adjacent to the presumptive inner ear also begins to grow; these cells will become the ossicles. As the middle ear cavity grows, it sends extensions out and around the developing ossicles, so that the ossicles gradually become suspended in the middle ear cavity. In addition, as the middle ear cavity approaches the developing ear canal, the wall of the middle ear cavity and the wall of the ear canal form a "sandwich" of mesenchymal1 cells. This sandwich will become the tympanic membrane.

The depression that will form the ear canal grows into the head, toward the developing middle ear. The open end of this tube closes off early in gestation and does not reopen until around the time that responses to sound begin. In mammals, a slight bulge above the depression will form the pinna. The basic shape and configuration of the pinna may be evident quite early in development (e.g., Carlile, 1991).

Inner Ear

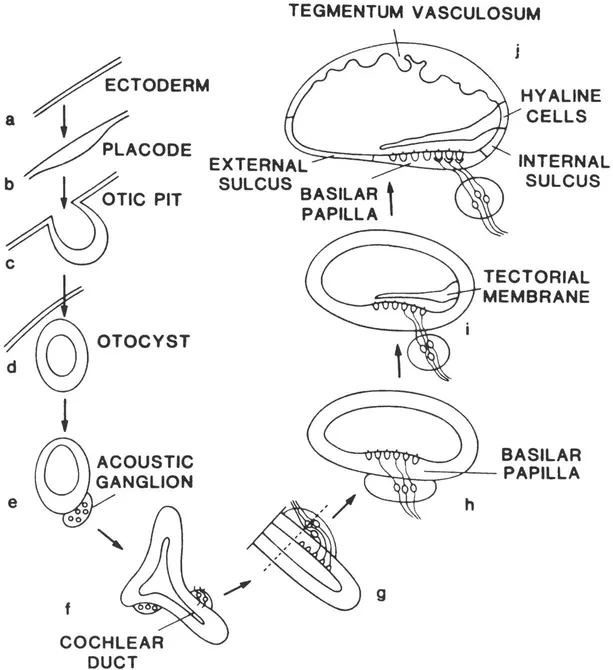

The process of inner ear development in chicks is illustrated in Figure 1.1. The otic placode forms a depression as it grows into the head; eventually, the external edges of the placode close to form the fluid-filled, more or less spherical otocyst. As this change in shape is occurring, the cells of the developing inner ear continue to proliferate, and, by the time the otocyst is formed, the cells that are destined to become the vestibular and spiral ganglia migrate away from the otocyst (e.g., Meier, 1978). As the otocyst continues to grow, it elongates to form the cochlear duct. In mammals, the otocyst coils as it elongates.

Around the time that the elongation of the cochlear duct is complete, several important events occur in the development of the organ of Corti. The region where the organ of Corti will form is already thicker than other regions along the wall of the cochlear duct. Then the soon-to-be hair cells, still indistinguishable in appearance from

FIGURE 1.1 A schematic representation of the development of the avian cochlea. The basilar papilla is the avian homologue of the mammalian organ of Corti. The tegmentum vasculosum is the avian homologue of the mammalian stria vascularis. In panels /and g, the cochlear duct would be coiled in mammals. The regions labeled "external sulcus," "internal sulcus" and "hyaline cells" contain support cells. From K. L. Crossin, et al., "Modulation of Cell Adhesion Molecules During Introduction and Differentiation of the Auditory Placode" in Auditory Function: Neurobiological Bases of Hearing, G. M. Edelman, W. E. Gall, and W. M. Cowan (eds.). Copyright © 1988 Neurosciences Research Foundation, Inc., New York, NY. Reprinted by permission.

supporting cells, begin to migrate toward the inner surface of the cochlear duct (e.g., Whitehead & Morest, 1985a, 1985b). Afferent nerve fibers can now be seen contacting the base of the presumptive hair cells (Whitehead & Morest, 1985a). Once the presumptive hair cells reach the inner surface of the cochlear duct, they begin to form cilia. When mammalian hair cells can first be recognized, they already form a single row of inner hair cells and three or more rows of outer hair cells, separated by some supporting cells. Efferent fibers enter the cochlear duct later, growing toward the hair cells through the channels where the afferents have preceded them (Cohen, 1987; Whitehead & Morest, 1985a).

An important observation about cochlear development is that events do not happen simultaneously along the cochlear duct. Events such as the movements of presumptive hair cells and the ingrowth of nerve fibers occur first near the base of the cochlear duct and last at the apex. This base-to-apex gradient is evident in nearly all aspects of cochlear development. One exception to the rule may be the birth of hair cells and supporting cells. In one study, Ruben (1967) reported that hair cells and supporting cells at the apex of the cochlea underwent their final mitoses before those at the base.

Tissue Interactions During the Development of the Ear

As the previous descriptions imply, the development of the subdivisions of the ear proceeds separately. However, this does not mean that the development of one part of the ear is independent from that of the other subdivisions, or from that of other, nearby tissues, Yntema (1950) first demonstrated the importance of tissue interactions in the formation of the amphibian ear; more recent investigations have elaborated on his findings in mammals. For example, the development of the ossicles may depend on the presence of the otocyst (discussed by Van De Water, Maderson, & Jaskoll, 1980). Similarly, the formation of the otic placode, the formation of the otocyst, and the differentiation of sensory structures depend on the presence of presumptive neural tissue (Noden & Van De Water, 1986). Furthermore, the developing otocyst and the adjacent mesenchyme that will become the bony labyrinth exert mutual influences on growth and differentiation in an age-dependent manner (Frenz & Van De Water, 1991; Van De Water, 1981). The issue of whether the differentiation of hair cells depends on their innervation has received considerable attention. Despite the apparent coincidence of hair cell differentiation and afferent innervation, it appears that otocysts grown in the absence of spiral ganglion cells still differentiate normally (Corwin & Cotanche, 1989; Noden & Van De Water, 1986; Van De Water, 1976). Interactions of cells with their environment are, thus, highly characteristic of auditory development. At the same time, it is evident that coincidence of events need not indicate that those events are dependent.

The Central Auditory Nervous System

The auditory nervous system develops in parallel with the auditory periphery, and, like the periphery, the central system is highly dependent on interactions between cells for normal development.

General Observations

Many important events in the development of the auditory nervous system occur before an organism responds to sound. Neurons proliferate, migrate to the appropriate locations within the brain, and form connections with other neurons. It is interesting that these events are occurring at the same time that the ear is developing. In mice and rats, which have identical developmental time courses, the brainstem and thalamic neurons are born between 10 and 20 days of gestation (Martin & Rickets, 1981). Auditory nerve fibers form connections in the cochlear nucleus at about the same time that they form connections in the cochlea (e.g., Parks, Jackson, & Conlee, 1987). Connections between brainstem nuclei and connections between the thalamus and the cortex are formed as the cochlea continues to differentiate (e.g., Friauf & Kandler, 1990; Repetto-Antoine & Meininger, 1982; Robertson, et al., 1991).

In addition, auditory neurons in many parts of the brain have developed many of the specific structural characteristics that they will exhibit in adulthood by the time an organism begins to respond to sound. Neurons in nucleus laminaris (NL), the avian homolog of the mammalian medial superior olive, have achieved their characteristic bipolar form (Smith, 1981). The arrangement of cells within the inferior colliculus is already adultlike (Repetto-Antoine & Meininger, 1982). However, many characteristics of auditory neurons remain immature when auditory responses are first observed.

As is the case for the cochlea, there are distinct spatial gradients in early auditory neural development. Altman and Bayer (1981), for example, reported that the birthdates of brainstem and thalamic auditory neurons tend to be ordered along the tonotopic axis of each nucleus. Neurons that will eventually respond to high sound frequencies are generally born before those that will respond to low frequencies in adulthood. Considering that the brain and the cochlea are not functionally connected at this time, the parallels in spatiotemporal developmental gradients seem remarkable.

Tissue Interactions During Early Neural Development

The dependence of auditory neural development on the presence of intact ears has been studied during this early period only in chicks. Levi-Montalcini (1949) first reported that the removal of one otocyst on the second or third day of gestation had no observable effect on the proliferation or migration of chick brainstem neurons. This finding has subsequently been replicated by Parks (1979).

Following otocyst removal, the normal connections between chick brainstem nuclei are formed, but by seven days of gestation an abnormal connection is also formed (Parks & Jackson, 1986). Nucleus magnocellularis (NM), the homolog of the mammalian anterior ventral cochlear nucleus, grows a connection to NM on the opposite side of the brain. Such a connection is seen neither in adult chickens nor in normal development. A very interesting aspect of this abnormal projection is that the contact between the axons from one cochlear nucleus and the cell bodies of the other resembles a cross between the contacts of NM axons with their normal target neurons in NL and the contacts that auditory nerve neurons make with NM neurons (Parks, Taylor, & Jackson, 1986). This observation suggests that both the pre-and postsynaptic cells play a role in determining the structure of the connections between them; thus, interactions between neurons are also evident in auditory development (discussed by Rubel & Parks, 1988).

Functional Development and Underlying Factors

In considering functional development, the focus is on the function of the organism as a whole rather than the function of the subdivisions of the auditory system. The discussion is organized around the development of two basic capacities, absolute sensitivity and sensitivity in noise, although other response properties are also considered.

Absolute Sensitivity

Ehret (1976, 1977) conducted two studies of the development of auditory behavior in mice that provides a starting point for discussing the functional development of the auditory system. In the first study, Ehret (1976) determined mouse pups' thresholds for pure tones of different frequencies presented in quiet; in the second study, Ehret (1977) determined thresholds for the same tones in broadband noise. The two studies used the same methods. The tones were presented from a loudspeaker placed in front of the animal. Ehret examined several behavioral responses to sound, in order to accommodate the response repertoires of mice at different ages. For the youngest mouse pups (9-11 days old), this was a stop in crawling in response to sound; for the older mouse pups (12-24 days old), it was a pinna movement; for the adult mice (2-3 months old), the response was eyelid closure conditioned to occur on sound presentation by pairing the tone with an electric shock. Thresholds for a group of 17-to 19-day-old pups were also determined using the conditioning procedure to see how the response measure may have contributed to the thresholds obtained.

The thresholds in quiet are shown in Figure 1.2. None of the 9-or 10-day-old animals showed a response to tones at the highest level that Ehret could present. Beginning at 11 days of age, however, the mouse pups began to respond to tones presented at 65 to 75 dB SPL, but only when the tones fell within a frequency range representing the low to middle part of the mature range of hearing. Between 11 days and 30 days, hearing changed in two ways. First, the threshold progressively decreased, by at least 40 dB. Second, around 14 days, the mice began to respond to lower frequencies and to progressively higher frequencies. The oldest pups tested with the pinna response were still 10 to 15 dB less sensitive than adult mice, but at least part of this difference can be accounted for by the difference in methods used to measure threshold. The 17-to 19-day-old pups tested with the conditioned eyelid response had thresholds about 5 dB lower than their thresholds measured with the pinna response.

Thus, Ehret (1976) noted a marked improvement in sensitivity in the days following the onset of hearing in mice. The initial response was limited to very high intensities and to a restricted frequency range. An initial rapid threshold improvement was greater at high frequencies, so that high-frequency thresholds approached maturity. Throughout the following period of slower improvement, low-frequency thresholds continued to mature. A similar pattern has also been documented in the behavioral responses of cats (Ehret & Romand, 1981), rats (Sheets, Dean, & Reiter, 1988), chickens (Gray, 1987b, 1992a; Saunders & Salvi, 1993), and tree shrews (Zimmerman, 1993).

What structural and physiological properties of the auditory system could be responsible for this change? In adults, the acoustic properties of the external ear and the middle ear dramatically affect absolute sensitivity and its dependence on frequency. Furthermore, the response of the cochlea is critical to mature absolute sensitivity. Logically, the efficiency with which information can be transmitted from the cochlea and through the auditory nervous system should also be a limiting factor. Of course, mouse pups may appear to be less sensitive than older mice because it is difficult for them to respond or because they are inattentive to some sounds. In this section, we will consider the contribution of each of these ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Series Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Early Functional and Structural Development of the Nonhuman Auditory System

- 2 Early Development of the Human Auditory System and Its Relationship to Nonhuman Auditory Development

- 3 Absolute Sensitivity

- 4 Factors Related to Thresholds in Noise: Intensity, Frequency, and Temporal Resolution

- 5 Other Response Properties: Development of Complex Sound Perception and Binaural Hearing

- 6 Effects of Experience

- Epilogue

- Appendix 1: Acoustics

- Appendix 2: Basic Anatomy and Physiology of the Auditory System

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Auditory Development by Lynne A. Werner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.