eBook - ePub

Collaborative Research And Social Change

Applied Anthropology In Action

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collaborative Research And Social Change

Applied Anthropology In Action

About this book

Community case studies are basic to anthropology, yet there are relatively few examples in which the promotion of social change has been the explicit goal of the research. The case studies included here are all "natural experiments" that involve long-term community-based research, close collaboration between researchers and representatives of the h

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collaborative Research And Social Change by Donald D Stull, Donald D Stull,Jean J Schensul in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Collaborative Research in the United States

In the United States, collaborative research can be traced to the work of Sol Tax and his students with the Fox Project in the 1940s and 1950s. While the visible accomplishments of this project were limited, it nevertheless established many of the principles of collaborative research. These principles include:

- Developing and testing theory on an ongoing basis in interaction with interventions or action (what Tax called "learning and helping").

- Ensuring consistency between project means and desired ends.

- Basing ends and weans on guidelines established by the host community.

These principles were utilized throughout the 1960s and 1970s by "action" or "advocacy" anthropologists as they applied research to community development in ethnic minority communities in the United States. Such anthropologists were successful in making research useful, but were less successful in involving community actors directly in research activities as a tool for change. By the mid-1970s this had changed somewhat as ethnic minority communities began to see the need for information in the advocacy process. This perception permitted the development of a new configuration in the integration of research and action in which anthropologists became collaborators with community activists in research directed toward social change.

The projects discussed in the following chapters all reflect this basic philosophy (for example, all but one of the accounts are coauthored by anthropologists and their collaborators). In each case, the anthropologists approached a local community with an interest in collaborating in the use of research for change purposes. Although these communitites--reservation Indians, urban Puerto Ricans, Punjabi immigrants—are diverse, they are representative of populations that have been the focus of traditional anthropological concern. In this regard, Barger and Reza's approach is noteworthy by introducing action research in a majority community to improve working conditions for a minority group.

Each case differs in the degree to which research was successfully introduced, carried out, and utilized in a collaborative manner. The work of Schensul and her associates in the Hispanic Health Council and the bilingual/bicultural education program undertaken among the Hualapai by Watahomigie and Yamamoto both reflect close cooperation between outside professionals and community representatives, resulting in highly successful outcomes. But in spite of sincere efforts on the part of both anthropologists and their community collaborators, project results may be mixed. The projects carried out by Stull, Schultz, and Cadue among the Kansas Kickapoo and Gibson among the Punjabis in "Valleyside," California suggest that "successful" projects are, as often as not, ones that only satisfy some of the people, to some extent, some of the time.

While these efforts vary in scope and duration, the anthropologists share a common bond in their lengthy associations with the communities or populations in which they work. Their experiences point to the great importance of long-term commitment by both anthropologists and community collaborators. It is this commitment, the authors suggest, that ultimately results in funding, quality research, and productive use of results for community institution building and positive social change.

1

Urban Comadronas: Maternal and Child Health Research and Policy Formulation in a Puerto Rican Community

Jean J. Schensul, Donna Denelli-Hess, Maria G. Borrero, and Ma Prem Bhavati

"Collaborative research" refers to a process in which university-trained researchers bring their skills and interests to bear on a community or institutional problem. The initial problem is often, though not always, identified by members of the institution or community. Once identified, it is negotiated and translated into researchable terms. Community or institutional participants then work with researchers through operationalization of concepts, research design, collection and analysis of data. Utilization of the information is planned and carried out jointly, often leading to "next steps" in the action research process (Schensul and Stern 1985).

This process is relatively clear-cut and described in the action research literature, when the emphasis is on research and action as separate though related phases of the same effort. In such projects, collaboration refers to the relationship between researchers and actors in the setting. Problems revolve around the methodology for empowering nonresearchers to engage in all aspects of the research process in the belief that full participation will lead to active and informed participation in its use (Borrero, Schensul, and Garcia 1982). Using research results is nowadays referred to in anthropology as "knowledge utilization."

The process is somewhat less clear-cut, however, when the interest of the researcher is to integrate research into intervention or ongoing social change programs and to encourage participants in an already existing social change network to see and utilize the value of research in interdisciplinary program design, implementation, and evaluation.

This paper will explore the latter situation. In so doing, it will refer to case examples from the Puerto Rican community of Hartford, Connecticut. The specific purposes of the paper are:

- To explore the notion of collaboration in applied research.

- To discuss a complex research and intervention program as an example of this approach.

- To extract principles of collaborative research applicable to other efforts in which applied social scientists are involved with community and institutional representatives to bring about social change.

Anthropology and Applied Research

Since anthropology is fundamentally a research-based discipline, applied anthropology must be understood as the application of anthropological research in the solution of human problems (cf. Kimball 1978). Over the past 50 years, the discipline has developed a number of terms to describe this process. For example, "applied anthropology" is associated with George Foster's (1969) original text and those times when anthropologists have been called upon to work either with national governments or international change agents in the implementation of change programs. Anthropologists have utilized research to reconcile local community needs, beliefs, and behaviors with these programs and to assess and explain program efficiency.

"Action or advocacy anthropology," on the other hand, stems from the work of Sol Tax and his students (cf. Gearing 1960; Peattie 1968) and later on Peterson (1974), Schensul and Schensul (1978), and others. It refers to the association of anthropologists with ethnic minority community activists in the United States and the use of research to facilitate the empowerment of local communities.

In most cases, however, regardless of their base, anthropologists interested in using anthropological knowledge for social change generally find themselves brokering between local communities and larger sociopolitical entities (Stull and Moos 1981). In so doing, they attempt to ensure that policies and programs are created or changed to suit the needs of local communities and are effectively implemented (Chambers 1985; Heighton and Heighton 1978; Hicks and Handler 1978). This process of negotiated change takes place in an environment--whether in the United States or elsewhere--in which the populations of concern have limited power, influence, and resources (cf. Bee 1982).

In this competitive environment, an effective strategy available to anthropologists is participation in the formation of community institutions that strengthen the involvement of Third World communities in national and international dialogue (J. Schensul 1985a). There currently is a sizeable body of literature that demonstrates how research can be an effective tool for initiating this process by: (1) enhancing a group's knowledge base; (2) integrating university and community resources around a common problem; and (3) training knowledgeable community research staff to take on leadership roles in further research and development (see Schensul and Borrero 1982; Stern 1985).

The 1960s and 1970s saw a flourishing of such community institutions, each advocating its own view of community needs. More recently, local community groups have found it less effective to advocate independently and have sought to form coalitions around social issues. Some have termed these coalitions "policy clusters" (Pelto and Schensul 1986; J. Schensul 1985b). Policy clusters cut across sectors to bring networks of people with different resources together to try to solve common problems on a broader basis.

The policy cluster is essentially an urban phenomenon. It is usually found in primary and secondary urban environments where multiple sectors vie for limited local and national resources. When policy clusters cut across class lines, they generally are responding to needs of the urban poor, assisted by "sympathetic sectors" among the local and national middle and upper classes.

When these coalitions systematically utilize research, they may be termed "policy research clusters." These policy research clusters includes (i) different disciplines; (2) different sectors; (3) different assumptions about research methods and what constitutes legitimate "data"; (4) different opinions as to the relative weight of research versus intervention; and (5) different opinions as to "theories of intervention."

Policy research clusters provide a context for collaborative research. Those interested in the collaborative research process must either form such coalitions or participate directly in their formation. Otherwise it is unlikely that social science research will be seen as central in the process of policy formulation.

Theories guide the policy cluster. These theories may be termed "theories of action" in that they are meant not only to direct research but to suggest directions for social change. It is quite common to find policy clusters in which several theories of action or intervention are active simultaneously. Confusion in discussion, planning, and policy generation most often arises when theories of action are unclear and conflicting. A commitment to research requires a theoretical framework. Thus, research can "force the issue" in the clarification of theoretical diversity in the policy cluster. It can do this in several ways, each appropriate for a particular problem and setting. For example, when information is required to arrive at decisions concerning program or legislative direction, one or a combination of theoretical frameworks guide research. Or a program may be established to test a theoretical proposition, and an evaluation research design is generated to determine its effectiveness (Cook and Campbell 1979). The evaluation design then becomes an important part of the program's logic.

In the following section, we will discuss the applicability of the concepts "policy cluster," "collaborative research," "knowledge utilization," and "theory of action" in the context of a maternal and child health program in the Puerto Rican community of Hartford, Connecticut. This program began with a policy cluster consisting of local and state representatives working together to plan a local program. Throughout the life of the program its reference shifted back and forth from local to state and national levels. At various points in the program's history, different members of the original policy cluster came together to influence opinion about the program, to shape the direction of the program and of information collection, and eventually, in some instances, to oppose it. This paper will describe the program, the history of shifts in the program, policy clusters, and research strategies. It will conclude with implications for collaborative research in intervention programs.

History of the Comadrona Program: Conceptual Framework and Program Structure

In August 1982, representatives of the Maternal and Child Health Section of the Connecticut State Health Department, the Hartford City Health Department, and the Hispanic Health Council met to define maternal and child health problems in the Puerto Rican/Hispanic community of Hartford and to respond to a request for proposals for a Title V national demonstration grant in the area of maternal and child health (MCH). Included in this meeting were a number of physicians, a Puerto Rican community activist, and a medical anthropologist. The city health department offered statistics on Hispanic maternal and child health; the Hispanic Health Council provided data on the importance of social supports in access to and compliance with prenatal care (Schensul and Schensul 1982); and the state health department offered technical assistance with grant writing.

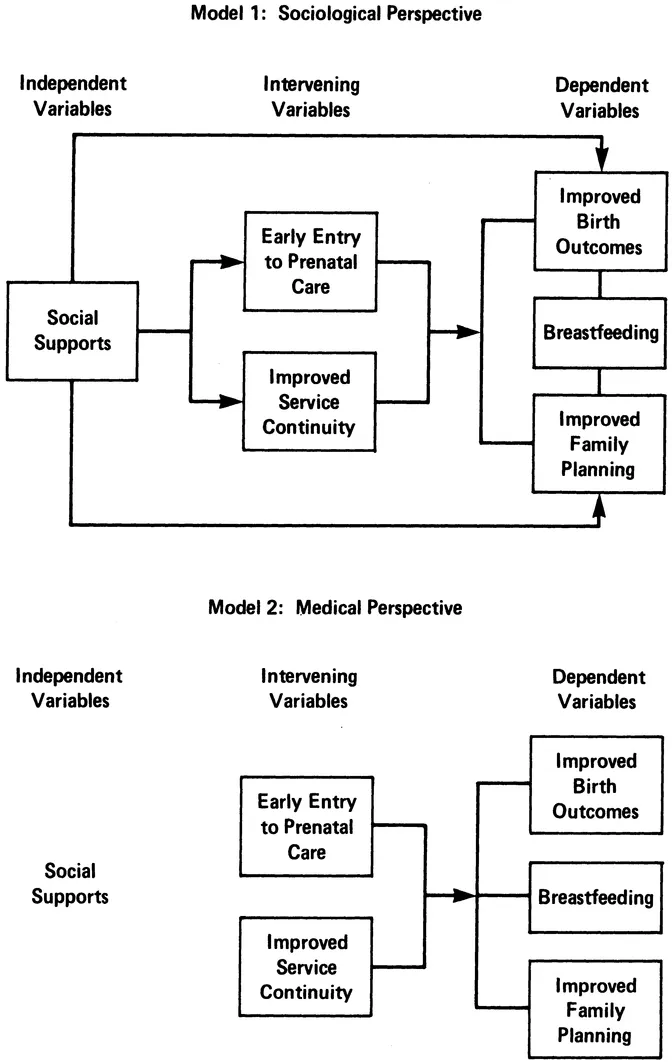

Two sets of assumptions were combined into a program model. The first was medical in origin and argued that early and continuous prenatal care was central in influencing positive birth outcomes for pregnant high-risk, low-income Hispanic women. The second, sociological in origin, argued that social supports were central in influencing prenatal health behavior, including access, compliance, and health maintenance. They were combined in the concept of the traditional birth attendant in Puerto Rico, the comadrona, a powerful cultural symbol combining good prenatal care with strong social and community supports.

The two assumptions were to some extent, however, contradictory (see Figure 1.1). The sociological perspective led to a model for intervention and evaluation in which the primary emphasis lay with the relationship between the independent and intervening variables. The intervention, as carried out by the comadrona, involved the development of community and family supports during the prenatal and postnatal periods. Measurement of success in this model did not require a large sample; instead, it required careful documentation of the building of support systems and the relationship between social support development and access to care.

The medical framework, on the other hand, emphasized the relationship between the intervening variables and the dependent variables. The role of the comadrona was defined as improving access to and continuity of care. The test of success was the degree to which improved service access would influence stated outcomes; measurement of success in this model -- in conformity with standard epidemiological research and health services practices--was seen as requiring a large sample size.

The crucial distinction between these two models was unclear in the design phase. While the program staff came to advocate the first model, in reality the second model, with its associated large sample size, was selected by the policy cluster as the basis for the program. In addition, the second model was attractive because of the policy cluster's interest in collecting data on pregnant Hispanic women. The larger sample size was seen as providing more data.

Figure 1.1 Alternative Models for Research and Intervention to Improve Maternal and Child Health

The policy cluster submitted a grant application based on the still unclear combination of first and second models, and in September 1982 the Connecticut Department of Health Services (DHS) received a three-year grant for the Hispanic Maternal and Child Preventive Health Network, the Comadrona Program. The Community Health Division (CHD) and the Maternal and Child Health Section of the state health department contracted the funds to the Hispanic Health Council (HHC) of Hartford, Connecticut, The policy cluster was differentiated into two bodies--the administrative team, consisting of members of the state Maternal and Child Health Section and the HHC, and the technical advisory team, consisting of members of the city health department and other MCH programs in the city.

Program Theory: The Comadrona Reinstated

The stated overall purpose of the Comadrona Program was to prevent perinatal and child health problems in low-income Puerto Rican families and to enhance pregnancy outcomes for mother, child, and family by developing and strengthening support networks in the community. The model was derived from an understanding of: (1) the importance of social supports in affecting perinatal behaviors and health outcomes for mother and child (Gottlieb 1981; Schensul and Schensul 1982); and (2) the traditional role of the birth attendant in Puerto Rico, which combined biomedical, social, and psychological services to women, their families, and the new baby.

The comadrona was the traditional midwife/birth attendant in Puerto Rico prior to the introduction of U.S. health care delivery systems. The comadrona was available for consultation during pregnancy, for delivery of the child, and for provision of postpartum support for the family, particularly during the 40-day period after birth referred to as the cuarentena.

With the introduction of hospital-based health care, the role of the comadrona shifted from providing direct care to providing linkages to the health care system for pregnant women. The primary responsibilities of the comadrona over time have been to provide women and their families some aspects of perinatal health care in both rural and urban areas, links to other forms of health care {indigen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- About the Book Editors

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART 1 COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH IN THE UNITED STATES

- PART 2 COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH IN THE THIRD WORLD

- PART 3 CONCLUDING COMMENTS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- CONTRIBUTORS

- INDEX