![]()

1

The Egyptian Experiment

Can a pre-modern society achieve a modem demographic profile? That is, can birth and death rates in lower income nations be made to fall to Western European levels before a general process of economic development and modernization has occurred? So intensely has this question been discussed in international circles over the past two decades, that the United Nations Population Division entitled its two tomes of scientific papers published after the 1974 World Population Conference The Population Debate (United Nations, 1975).

The case of Egypt is especially relevant to this debate. It is a low income country whose leaders introduced a family planning program decades ago in order to accelerate economic development. More recently, however, they essentially reversed the approach by designing a program based on the theory that economic development was necessary to stimulate family planning. Accordingly, an ambitious scheme of community development cum family planning was launched in a large number of Egyptian villages. Did it work? Insofar as it did, could its success be attributed to either community development or the synergistic combination of development and family planning? To answer these questions, in 1982 a large field project was undertaken whose results are the subject of this monograph.

The Egyptian Setting

It is not difficult for a student of Egypt to conclude that the country is unique. Certainly its geography alone qualifies it as highly unusual. With 95 percent of its land area in desert, in 1985 over 1,100 persons were living on each square kilometer of inhabited land along the narrow strip of river that has dominated economic and social life for centuries. However, the unusual geography is not matched by economic, social, or demographic uniqueness among developing nations. In 1982 Egypt's 44 million people had an annual average income of $670, placing the nation 69th among the 108 countries ranked in the World Bank Atlas (World Bank, 1985)—poor, in short, but not exceptionally so. Indeed, the Bank considers Egypt to be in the "lower middle income" category, along with such nations as Nigeria, Thailand, and the Philippines. Moreover, thanks to gains in petroleum exports, tourism, and remittances from emigrants, per capita growth in the GNP 1973-82 has been at the unusually high rate of 6.6 percent per year, exceeded during this period by only three other rather exceptional countries—Hong Kong, Malta, and Macao (World Bank, 1985).

With respect to two standard measures of health, Egypt ranks somewhat lower but is still a good distance from the bottom. In 1982, with 104 infant deaths per 1,000 births and a life expectancy at birth of 57 years, Egypt placed 86th and 78th, respectively, among 126 nations ranked by the World Bank (1985).

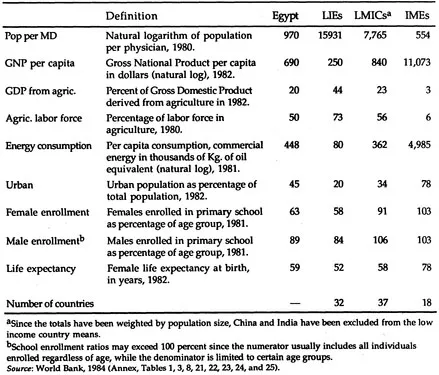

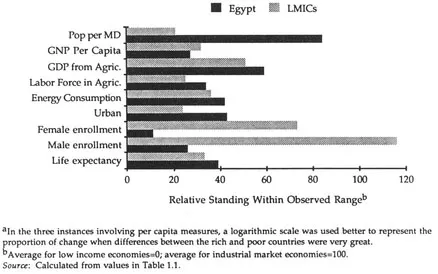

Table 1.1 compares Egypt with three other groups of nations: 32 countries designated as "low income economies" (LIEs) by the World Bank (1984); 18 countries designated as "industrial market economies" (IMEs); and 37 countries (including Egypt) considered "lower middle income" countries (LMICs). Because the difference between the wealthier and poorer countries is so great, we created a scale in which for each of nine development variables the zero point is the mean (weighted by population) of the LIEs, and 100 percent is represented by the weighted mean of the 18 IMEs. We will measure Egypt and other middle income countries against the gap between these groups of poor and rich countries. Each bar of Figure 1.1 represents the proportion of the difference between rich and poor countries that has been achieved by Egypt and by other "lower middle income" countries. In terms of physicians per capita, for example, Egypt has "traveled" 84 percent of the distance between the 32 poorest and the 18 richest countries. The other "middle income" countries have only gone 21 percent of the distance. Egypt is also relatively more urbanized, standing midway (43 percent) between rich and poor countries, a position considerably beyond that of its economic peers (24 percent). On most items it is about at the level of the 37 LMICs. However, it is clearly deficient in education, especially in female enrollment, where it is scarcely better than the poorest countries, and is notably below those nations in the same economic category. The overall picture is of a somewhat better than average less developed country (LDC) with a rapidly improving economy. Other than the rather low values for education, there is nothing here to lead us to expect unusual demographic patterns, assuming that the latter are closely related to socioeconomic development.

There are at least two features not unique to Egypt but special to the region that could relate to fertility levels; the status of women and

TABLE 1.1 Definitions and Weighted Means for Variables Used in Figure 1.1

the traditionalism of Islam. These two aspects are, of course, related. Thus, a recent review of fertility trends in 33 Moslem countries states that "although a direct connection remains to be established, the subordinate position of women, which appears to be an entrenched part of Moslem culture, is usually suggested as an important factor maintaining fertility of Moslem women at a higher level" (Nagi, 1984:198). Despite the fact that Islamic law grants married women independent property and certain legal rights, other aspects of the law have the effect of subordinating the female: "the religio-legal sanctioning of polygamy; the husband's unilateral power in divorce, in custody over his children, and in enforcing the return of a rebellious wife; unequal female inheritance; and unequal weight of a woman's legal testimony" (Youssef, 1978:85). Whether attributable to religion or to more general traditions, "All seems to point to the maximization of natalist tendencies. Muslim women are fully cognizant of the need to obtain marital position and motherhood for commanding respect and status in their own kin group and community. . . . Women derive status from motherhood even when divorced or rejected for a second wife. Offspring guarantee to the woman status and respect that extends far beyond her position in the conjugal home and reaches into the heart of her own family and the community's evaluation of her. Hence we may expect women to continue childbearing activities throughout their reproductive years—whether they are happy in their marriage or not" (Youssef, 1978:86).

FIGURE 1.1 Measures of Relative Development: Egypt and 37 Lower Middle Income Countries (LMICs) Compared with 18 High and 32 Low Income Countries3

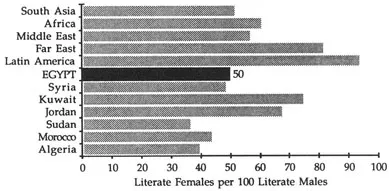

The norms that circumscribe female freedom and emphasize the roles of wife and mother have important consequences for female education and employment. According to the 1976 census, 71 percent of Egyptian women over ten years of age were illiterate, compared with only 43 percent of Egyptian males. That the ratio of female to male literates is especially low in Egypt can be seen from a comparison with ratios in other parts of the world. Figure 1.2 shows Egyptian women to be especially disadvantaged when compared with those in Latin America, the Far East, and Africa, and even when compared with the Middle East in general.

The proportion of women working in Egypt is also very low, and few of these work in the modern sector.1 According to estimates made by the International Labor Organization, only 6 percent of women were working in 1975. This was among the lowest rates in the world, matched only by those in other Muslim societies. Since such estimates are usually based on statistics that ignore female contributions to agriculture, the

FIGURE 1.2 Female Literacy Ratio, Selected Countries Source: Constructed from data in Sivard, 1985.

FIGURE 1.3 Rural Female Employment, Selected Countries Source: U.N., Dept. of International Economic and Social Affairs, 1985:30.

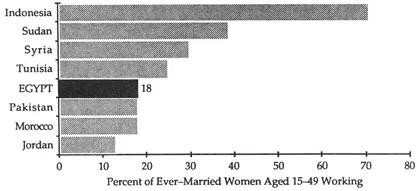

World Fertility Survey took special pains to get more accurate data by including in their employment question reference to women who "sell things or have a small business or work on the family farm." This question produced an estimate of 18 percent currently working among ever-married women aged 25-49; and a figure of 14.5 percent for women of no education—who make up the large majority of the sample described in this book (United Nations, 1985a: 16). Figure 1.3 shows comparative data for the rural areas of a number of countries with large Muslim populations that were included in the World Fertility Survey. Egypt's proportion of working women is among the lowest of these nations.

The Islamic religion has long been regarded as an important obstacle to fertility decline, either directly through pro-natalist or anti-contraceptive teaching or indirectly through its ideology of fatalism and conservative teachings on women. Lorimer considers Islam a religion that "gives strong and unequivocal emphasis to high fertility" (cited in Gadalla, 1978:17), and Fagley regards many of its emphases as pronatalist (cited in Gadalla, 1978:17), Kirk (1966:567) concluded that Moslem natality: "(1) is almost universally high, (2) shows no evidence of important trends over time, and (3) is generally higher than that of neighboring peoples of other major religions. Such observations do not apply to any other major world religion. . . . Empirically Islam has been a more effective barrier to the diffusion of family planning than Catholicism." A more recent and comprehensive review of 33 Moslem countries reinforces Kirk's conclusions: "(1) Moslem fertility remains universally high and is generally higher than in non-Moslem countries in the same region; (2) very few Moslem countries have succeeded in bringing down their level of fertility to justify a search for the predictors of Moslem fertility levels; (3) in spite of a sufficient range of variations in the economic and social correlates of fertility, the corresponding fertility variables in these countries do not suggest that the reproductive behaviour of Moslem women has reacted to such variations" (Nagi, 1984:189).

As far as explicit religious ideology is concerned, Egyptian religious authorities had made it clear, even before the National Family Planning Program, that Islamic teaching was not opposed to family planning. Thus a Fatwa issued in 1937 by the Mufti of Egypt, Sheikh Abdul-Majid Salim, stated that "either husband or wife, with the permission of the partner, is allowed to take measures to prevent entrance of the seminal fluid into the uterus as a method of birth control"; and "it is permissible for a pregnant woman to terminate pregnancy in the early months before fetal movements occur, if the health of the mother is endangered" (cited in Schieffelin, n.d.:11-12). In 1953 the chairman of Azhar University's Fatwa Committee, Mohd Abdul Fattah el Enani, stated that "the use of medicine to prevent pregnancy temporarily is not forbidden by religion, especially if repeated pregnancies weaken the woman" (cited in Schieffelin, n.d.:13).

However, once the program was launched it became clear that not all local and village religious leaders were aware of or in agreement with the authorities. In a 1969 pamphlet issued by the Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, the Minister of Wakf (religious endowment) found it necessary to state that "the role of the religious leader is to clear suspicion that family planning is against religion" (cited in United Nations, 1985c: 18).

With current fertility well below other Muslim countries, the barriers of male dominance and Islam would seem surmountable. But these cultural aspects could certainly affect such critical variables as the knowledge, approval, and adoption of contraception, which, in turn, should influence overall demographic trends through their impact on fertility.

Population Trends

The history of population increase in Egypt shows a familiar accelerating curve (Figure 1.4). Between 1897 and 1947 the population doubled, but the cultivated area scarcely changed, increasing only from 4.9 to 5.3 million feddans (a feddan = 1.04 acres). Between 1947 and 1976 the population roughly doubled again, while the cultivated area rose only slightly to 6 million feddans. Thus, in the first 80 years of this century, cultivated acreage per capita declined from .53 to .15. According to United Nations (UN) medium projections, the population will almost double between 1980 and 2010, reaching nearly 100 million by the first quarter of the next century (United Nations, 1985b:230).

The Total Fertility Rate (TFR—the number of births a woman would have if current age-specific birth rates prevailed throughout her reproductive life) fluctuated around 6.5 births per woman between 1936 and 1960, about what could be expected in a developing country where contraception was scarcely practiced and age at marriage for women was moderate (around 20). Over the next two decades fertility declined by at least one child, both because of an increase in age at marriage and because of a decline in marital fertility. A more recent analysis by Coale suggests an even sharper national drop, from 7.1 in 1960-65 to 5.3 in 1975-80, but essentially no change since then (cited in Kantner, 1984:31).

The current TFR of 5.3 children can scarcely be described as low, but, according to World Fertility Survey data, it was about two children less than in Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, and about one child less than in Bangladesh and Pakistan at...